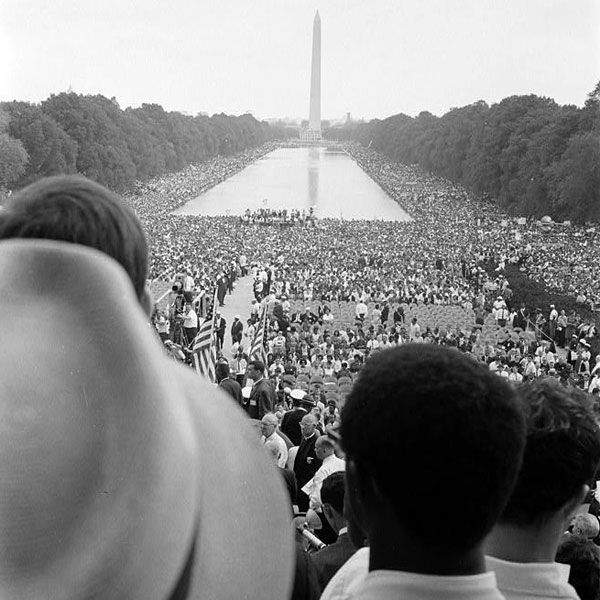

That was August 1963 and, of course King was very much present that day. It was really near the beginning of the civil rights movement. It was already, what?, six, seven years after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, and about three years after the lunch counter sit–ins began in, what?, North Carolina and that area and a lot of civil rights activity, and a march on Washington was planned. I think John Kennedy was president at the time; it was a few months before he was killed. The administration really didn’t encourage this large march and nobody knew quite what was going to happen, and it was very definitely a racially mixed march, and the idea, of course, was a peaceful march but demanding civil rights basically for people of color. And I got involved—well I was busy that summer, I was a young faculty member with two–and–a–half children and I was actually doing research on Long Island that summer at National Laboratory there. I and two of my friends decided at the last minute to go down to the march. And, we didnt know what kind of march it was going to be; we thought of course there might be some violent opposition to us. We had no idea what Washington was going to be like. We actually ran an experiment at the lab all day until about six p.m. and then got in the car and drove to Washington. And, it wasn’t really a hardship march. We got to the city, Washington, maybe two. We had a room at the Sheraton. We got up the next morning; we took a taxi to the march [laughs], and for several hours there were lots and lots of people there of course, and we just milled around in the general area of the Washington Monument and eventually we all started moving in the general direction of the Lincoln Memorial. Eventually you couldn’t get any closer to the Lincoln Memorial so we sat down on the side of the wading pool and speeches began. One thing that was remarkable about the day was—it was very much, of course, a mixed white and black crowd and everybody was—friendly. There was really a good feeling in the air, and then when the speeches began—it was hot; people were getting hungry; we were getting hungry, and the speeches tended to be kind of repetitious, and then all of a sudden, we weren’t even paying much attention—I wasn’t—as to exactly who was speaking when, and somebody started talking and I realized—this guy’s different, a real speaker, and of course it was Martin Luther King. And, that was a, a very emotional moment; it was, what?, ten minutes perhaps, and I’ve watched the video of that occasion several times since then and it’s still a powerful thing to see. He’s quite a speaker and the “I Have a Dream,” everybody ought to see that video. Now, there was, there was really such a feeling of optimism in the air. I mean, things were happening. Kennedy was sort of resisting, but there was there was going to be a Voting Rights Act, though it didn’t come until Johnson was president and pressured Congress into doing it, but you knew that things were moving and, it was really this wonderful feeling that after all this time, 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, that the race problem was gonna get settled. Well it hasn’t been settled yet but there was a great feeling in the air.

One of the memories I have of that afternoon—we had driven down in one of our own cars, but driving back on the Baltimore–Washington expressway looking out the back window and looking out the front window and just seeing, just wall–to–wall buses, hundreds of buses, going back toward Baltimore, going back toward Philadelphia, New York City, and of course people had come from all over the South, too, and what they were going back to was a little bit different from what we were going back to. It was quite a moment in the, well in American history. Nobody, including the Washington police, knew what might happen, but as far as I know there was absolutely no violence that day at all. Not only were there sort of more or less equal numbers of blacks and whites, probably more blacks than whites, but there was no blacks crowding together, no whites crowding together. What’s happened when we’ve had more black students at the college where I teach—which is typical I think—Amherst College, that the black students tend to eat together and live together, and ’tis all understandable, but, it’s sort of too bad, and that day there wasn’t any feeling like this is a white part of the crowd and this is a black part of the crowd.