by Susan McGowan

Primary and Secondary Sources

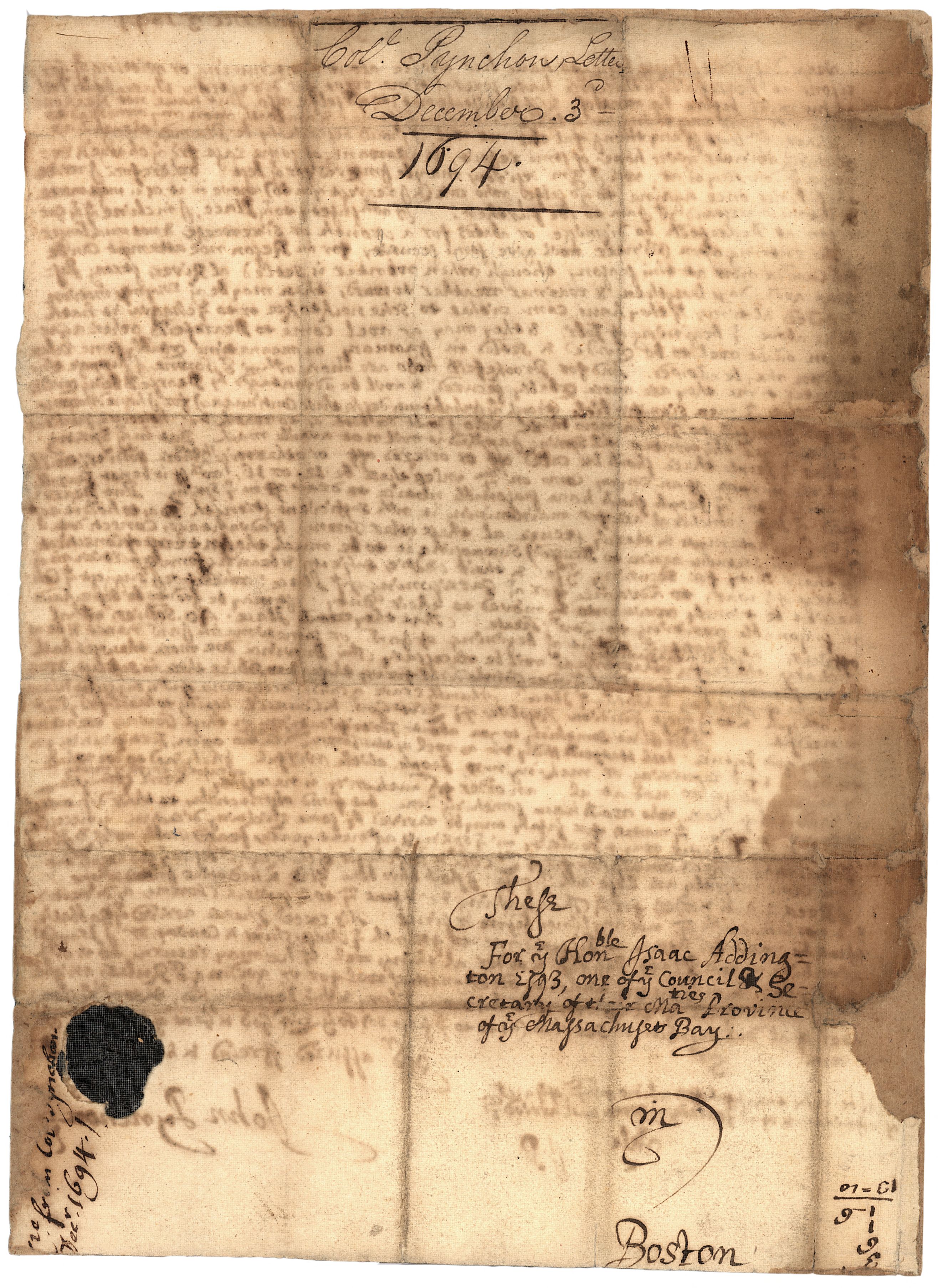

Primary sources:

- Primary source documents are those written at the time of the period under study.

- Taken together, primary sources provide evidence that later historians use to interpret history.

- Primary sources are the building blocks of historical scholarship.

What are they?

| Official/Legal | Personal | Financial | Communications |

|---|---|---|---|

| government records | letters | invoices | newspapers |

| deeds | diaries | bills | advertisements |

| wills | journals | ship records/logs | broadsides |

| inventories | travel logs | account books | maps |

| court documents | |||

| military records | |||

| tax records | |||

| census records |

“Interrogating” Primary Sources:

In order to effectively use primary source materials we must ask questions of them to reveal information contained within them.

- Who wrote this document, and what does this tell us about their perspective? For instance:

- a. What was this person’s “point of entry” into the world?

- b. What was this person’s role in their society? (government official, minister, merchant, midwife, land owner, farmer, etc.)

- c. What was this person’s world-view (religious perspective, economic interests, political ideology) based on who they are?

- d. What might be this author’s social status and education?

- Knowing what we know about this person, why do you think he/she wrote this document?

- Who was the intended audience for this document? What were its uses?

- What were the cultural and historical contexts and the environment in which this document was written? For instance:

- a. What was the political climate at the time? Was it written during a time of war? Was this a time of great change, or were the dominant groups working to keep the status quo?

- b. What assumptions did that author’s society hold about people of color?

- c. What were the roles and expectations of men and of women at that time?

Secondary Sources:

1. Secondary sources are written “after the fact” – that is, at a later date.

Usually the author of a secondary source will have studied the primary sources of an historical period or event and will then interpret the “evidence” found in these sources into what he/she believes is a coherent history based on what he/she believes happened.

Like cultural practices and beliefs, historic interpretations change over time. We should interrogate the secondary sources with the same questions we ask of primary sources.

Caveat:

Prior to 1960, historical narratives were often written from the dominant cultural perspective. The history and perspective of people of color, women, and working classes were often considered either not important enough to include or were written to justify the social structure as it was. (the winners write the history)

Since 1960, scholars in many fields of history, anthropology, archeology began asking new questions of the primary sources and discovering new sources. This work uncovered new understandings about these groups, and the stories they told began to be more complex, from different points of view.

*** It is important to look at when a document was written, whether it is primary or secondary, and place that document in its historical context.

Vocabulary

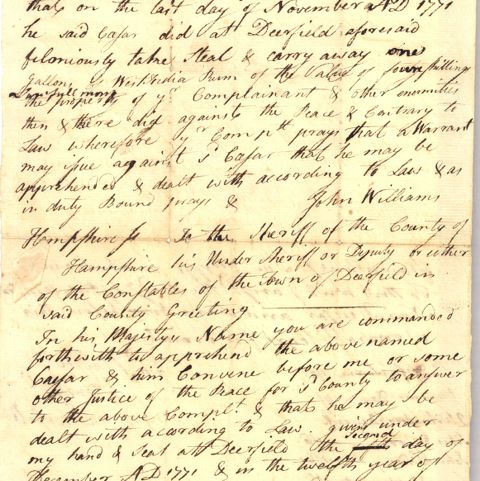

Vocabulary for assistance in translating primary documents

“Aforesaid” – what has been said, or usually, the name of the person, mentioned previously

“Moveables” – all possessions inside the house that are not nailed in or down

Estate, real – land

Estate, personal – everything but the land

“Ym” – them (with the “m” raised) Usually you can translate the “y” as “th” –as in yt = that; ye = the

“art and mystery” – all apprentices learned the “art and mystery” of the trade they were studying without benefit of written words; the information was passed from the master to the apprentice by word of mouth; this includes the art and mystery of housewifery where a mother or grandmother trained the female children

“s” or “f” – the letter “s” in the middle of the word usually is written to look like our modern “f” as in Maffachufetts.

“ae” – “aetatis” = in the year of their age

“viz” – namely

quotation marks, in the 17th century and the very early 18th century, often appear on the line as commas do, rather than above the word as they now do

“relict” – widow

“cubberd,” “cubert” – cupboard

“lanthorne” – lantern

“looking glass” – mirror

Do – (with the “o” raised) = ditto, the same as before

“Case of draws” – a chest of drawers

“Lumber” – stuff, miscellaneous possessions