by Susan McGowan

First, some questions to think about:

- Why do historians find graveyards useful for research?

- How and why are modern cemeteries different in appearance from the graveyards of the 18th and 19th centuries?

- Why are the early graveyards so far from the meetinghouses?

- Why do the early ones – those of the 18th and 19th centuries – usually have fences?

- Practically, what is the best time of the day and of the year to photograph a graveyard?

- And, what about the iconography? – those images that “decorate” the stones?

We’ll begin with the last question, because, even though it contains the largest word, iconography, it is probably the easiest question to answer. All of us know what icons are – pictures that represent some meaning – a shortcut image to give us a clue about meaning. Gravestone icons are just that. The carvings represent thoughts, beliefs, fashion, personal preferences, not to mention the skills – or the lack of skills – of the particular carver. As you look at the stones themselves or the digital images of the stones – you’ll begin to see a time pattern, a logical sequence, for the images. Just as the fashions in clothes, architecture, automobiles change, so did and do the fashion in gravestones.

Early colonists did not call a place for the dead a “cemetery” – a word that comes from the Greek and means “a sleeping place.” Instead they used the terms “burying yard,” “burying ground,” “burying place,” “bone yard,” and “graveyard.” In the Town records of Deerfield, Massachusetts, on March 5, 1703, there is a mention of “clearing the Burying place.” Usually these graveyards were sited away from the meeting house, where people attended worship, because Puritans did not believe that the dead should be put in a church yard or in sacred ground, since the salvation of the deceased was by no means certain. With their belief in predestination, nothing could be done to influence one’s fate after death. The body had no significance after the soul had departed. The ground, therefore, need not be sacred.

George Sheldon, in his History of Deerfield, reminds us that the site of the Deerfield burying ground had also been an Indian burying place – that eleven skeletons were found “buried in the Indian manner…on their right sides with head to the east facing the rising sun.” It was common for Native peoples to use land overlooking meadows or rivers as burying grounds.

Throughout the 18th century, and probably long after, New Englanders valued graveyards more as meadows than as sacred places. Many of us find graveyards uncomfortable, or even dreaded, places. As children we all have heard spooky stories associated with the dead and with cemeteries – graverobbers, werewolves, bats, vampires – but as we grow up and those images no longer give us the shivers, what is it about those places that make us uneasy?

Probably it is death itself, with the graveyard as a reminder more than anywhere else, of our short time on earth and our own ultimate death.

Most early New Englanders lived each day in preparation for death and judgment and they educated their children to do the same. Graveyards were created, in part, as teaching devices – as unmistakable reminders of the coming of death. To New England Puritans, death was an opening into another world, through which one’s soul passed into eternity. The body, the corpse – was only a memento mori (reminder or remembrance of death), a husk buried often without graveside prayer. The graveyard was a part of day-to-day life, never out of sight and never far from mind. They realized that the passing of time and our own mortality are powerful influences on our lives. Death was ever-present. Think about this statistic from another frontier settlement, Jamestown, Virginia: between December 1606, when the first vessels of the Virginia Company left England, and February 1625, 7289 immigrants came to Virginia. 6040 of the 7289 died in that 19-year period. Death was neither unusual nor unexpected.

Early graveyards may have resembled meadows, but they were not park-like. This was a time before people introduced plantings into the landscape – they were more interested in clearing the land, taming it of its wildness, than of planting shrubs and flowers – so there were no “ornamental” plantings such as you see around modern houses and in more modern cemeteries.

On March 6, 1720, the townsmen of Deerfield voted “to have the burying place enclosed with a fence.” The purpose of enclosing the space with a fence was not only to satisfy the need for tidiness and order, but also because burying yards were seen as grazing land. This was efficient use of land for feeding livestock, but also kept the grass cropped naturally, in the days before lawnmowers. In 1730, the Town voted to “let [lease] the Burying Ground for ten years” provided that “the Leasee must maintain the fence and must not Feed it with Any Creatures but Sheep and Calf.” [** Can you see the wisdom of rules against larger animals than sheep and calves?]

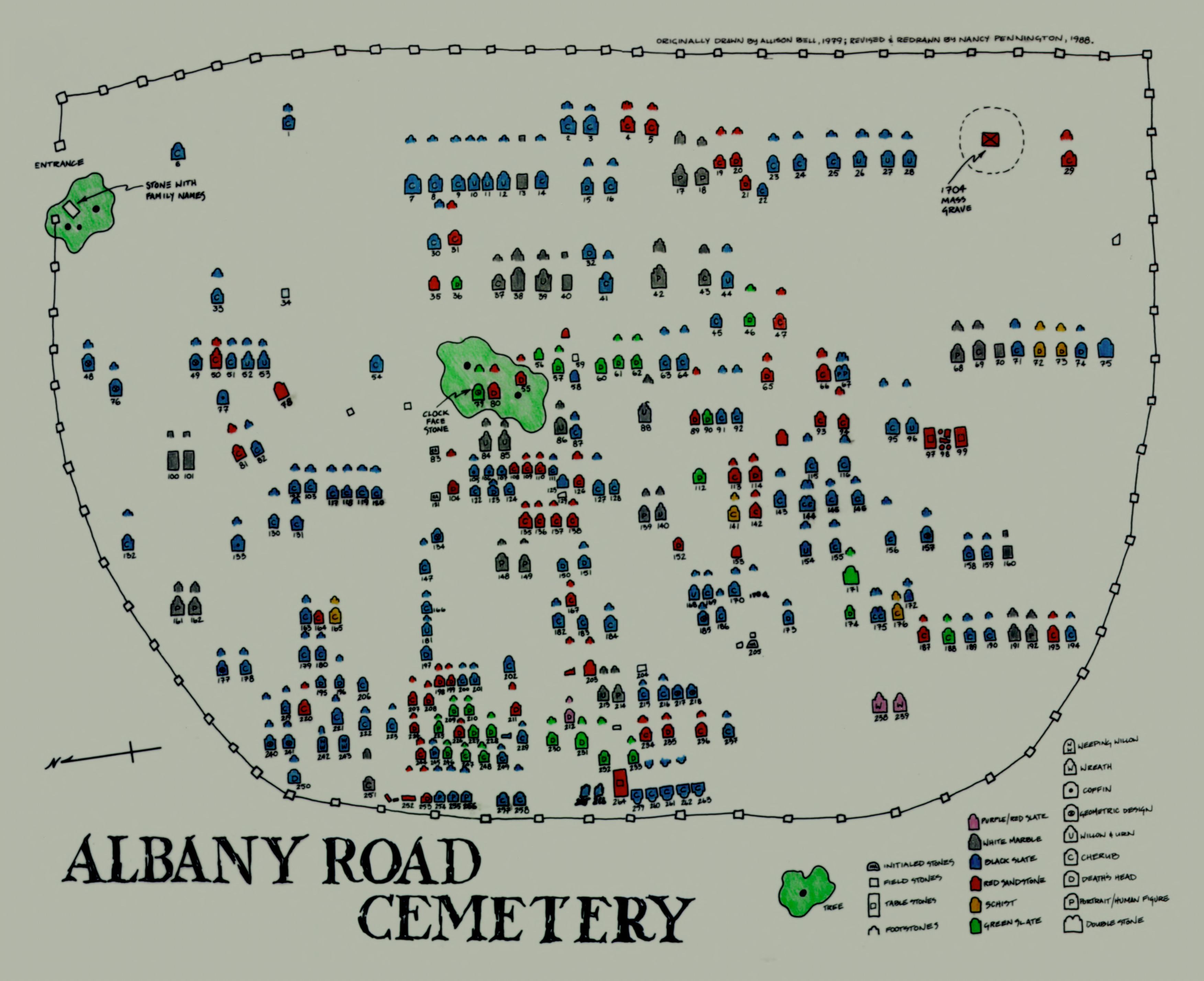

Throughout the 18th century, there was an increasing desire to mark the place of burial and to make some memorial to the deceased. In the first period of use of the Albany Road burying yard – 1703-1720 – few stones survive, and of those that do, some are backdated examples of later work. [make certain all understand the concept of “backdated.”] In the early days of the settlement of Deerfield, after the burning and abandonment of the town in King Philip’s War of 1675-76, and the resettlement in 1682, the town of Deerfield was an isolated cultural pocket. [**What kind of people come to the frontier? Wealthy people? Or poor people?**] Its people had few resources – neither cash, nor stones, nor the artisans to carve them – and they were unlikely, at that time, to import grave markers from Boston or from towns down the Connecticut River.

The earliest markers are plain, small, and with little ornament – some of them may have been made of wood, perhaps with the intent of a future replacement in stone. The markers served not only to mark the site of burial but also to instruct the living with the words and the iconography (the graven images or pictures).

Often the messages, whether text or images, were grim, particularly in the earliest years, reflecting the hardships of the early life on the frontier. They were not, however, unrelievedly gloomy and without hope. They were clearly loaded with warnings – some with skulls and crossbones were the most obvious – but many also evidenced signs and symbols of life – wings attached to skulls implied a lifting up to heaven – and vines that are carved into the edges of the stones suggest life… although there are those who will interpret vines and flowers – like people and all other living things – as symbols that flourish only for a short time before they, too, die.

A change in the quality of ornament was seen after a marriage of one Ebenezer Barnard of Deerfield to Elizabeth Foster of Dorchester (Boston) in 1715. With this marriage a kinship connection was established between a Deerfield family and a family of gravestone carvers in Boston. The Fosters were well-established as carvers in eastern Massachusetts and, in the coming years, they sold at least 24 gray-green slate stones to families in Deerfield. The lettering and the iconography on these Foster stones are similar – same nose, teeth, and wing patterns.

The stones in the Deerfield graveyards are of slate, sandstone, schist, and marble, and later of granite, polished or unpolished. Slate is among the most durable of stones. The small sediment allows for strong lettering and for detail. Granite and schist have very large crystals so the lettering, by necessity, must be more in block form, with fewer curls and swirls. One can get fine details in marble, but the stone “sugars” over time and the elements – rain, wind snow – blur it and after a while the fine details are gone. Native sandstone is not an enduring material, either as a hearthstone, a doorstone, a foundation for a building, or as a gravestone. Slate, however, can still be read clearly after more than 200 years.

When the Rev. John Williams died in 1729, his heirs purchased from Thomas Johnson I (1690-1761), of Middletown, Connecticut, “2 pairs of gravestones to mark his grave and that of Eunice.” Reverend Williams’s first wife, Eunice (Mather) was killed on the march to Canada in February 1704. She died near Greenfield and was buried in Deerfield, but without a permanent marker.

Gravestones were ordinarily sold in pairs – a headstone and a footstone – with the headstone larger and more ornately carved than the more modest stone to mark the foot.

The Williams’ stones are made of sandstone – native to Middletown, Connecticut, where the stonecutter did business – and are ornamented with death’s heads. There are 55 stones with this early style iconography in the Albany Burying Yard, some in sandstone and others in slate.

The death’s head may appear grotesque to us in the 21st century, but in 1729 it was not unusual; the head represented the spirit, the two mouths enabled the spirit to speak, and the nostrils permitted the spirit to breathe. The stones provided lessons to be learned. They not only marked the place where the remains of a body lay, but also proclaimed the freeing of the soul. That, of course, was the most important outcome of death – that the soul was now free to soar to heaven. The body itself was simply a housing or a shell – and after death it could be laid to rest in the ground, unconsecrated, unblessed ground.

The floral and vine decorations on many of the stones can be seen in furniture and in architecture, particularly doorways, in this time period.

Later in the 18th century, perhaps when life was somewhat easier for the English colonists, the macabre skeleton image, with its jack o’lantern features, gave way to more human-looking faces with rounded cheeks, more humanistic eyes complete with eyeballs, wreaths of curls surrounding their heads, and wings.

Sometimes these “angels” had wildly flapping wings, narrow eyes, and heads crowned with masses of wavy hair. Members of the Soule family of Barre, Massachusetts, were stone cutters and were the first itinerant stone cutters to appear in Deerfield.

More than 20 different carvers are represented on the Albany Road Burying Ground. One of the local cutters was Solomon Ashley, born 1754, to Reverend Jonathan and Dorothy Ashley. Solomon Ashley and a man named John Locke (1752-1837) were partners in the stonecutting trade. Their stones can be identified by three motifs: 1) a six pointed star or rosette within a circle; 2) a simply-executed angel with a few ringlets for hair and very plain, unfeathered wings; 3) by a long, narrow coffin with an occupant. By the time that Ashley and Locke were in business, after the American Revolution, harder stone material – marble, schist, granite – were in use and they allowed for less fine detail.

After the American Revolution, symbols associated with the neo-classical period began to be fashionable. These symbols, borrowed from ancient Greece and Rome, began to flourish in architecture, clothing, ceramics, silver, and even gravestones. Herculaneum and Pompeii, ancient cities in Italy, long buried by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, had been uncovered in the mid-eighteenth century and the wall painting and architectural details of these domestic buildings had already begun to influence design in Europe and in the British Isles. But the new thinking was slower to take hold in this country. Appearing in the late 1780s and continuing into the 19th century, the designs included urns, swags, wreaths, and weeping willow trees.

These neo-classical motifs appear also on needlework art created by the young women of the time. Mourning or memorial art was offered in the newly-formed academies and needlework schools. During the period following the death of George Washington in 1799 an unparalleled expression of grief swept the country. Mourning pictures became the fashion and daughters and other family members embroidered and painted these memorials in honor of their dearly departed. Mourning embroideries became the most popular form of schoolgirl needlework at many of the most fashionable academies throughout the land. Indeed, it was fashion, much more than melancholy which led to the overwhelming preference for mourning pieces.

The embroidered memorials were often executed in silk threads on a silk ground. Not all of the memorials included tombs, weeping willows and urns. Some took the form of coats of arms, embroidered on a satin ground with silk threads and enhanced by gold and silver threads. Other memorials included family registers with the names of the married couple and their marriage date, followed by the birth and death record of their children. Some were embroidered and others were lettered on paper. Later, printed forms were available for calligraphy and painted decoration. Records of family births and deaths had long been kept in special pages in family Bibles, but creating a record to put on the wall was a new idea.

In the graveyards, classical expression included the most expensive stones, the table stones – flat table-like stones supported by four or six columns, which were either plain or fluted. Their cost was approximately five times the cost of a set of head and foot stones. The table stones in the Deerfield burying yard show major amounts of deterioration. They are all made of sandstone and, because of the material and large flat surface exposed to the elements; none of the decoration nor the lettering is legible today.

Damage to many of the stones has occurred during the past 300 years. The weather is a major culprit – frost heaves cause cracks, settling, and tipping. Trees cause problems as their root systems expand. Some of the stones have toppled, perhaps nudged too often by one of the grazing calves or sheep, or from a too shallow original setting; some have been mended or even replaced. Vandals have not been a problem.

The Albany Road Burying Yard was closed for burials around 1800 when it was considered “full.” Only members of families who were already represented there could be added.

On March 3, 1800, the Town appointed a Committee to view a place for a new burying Ground. They were able to buy, for $12, a piece of Ground at the east end of Ebenezer Sexton’s homelot, and soon erected a “sufficient board Fence around the same.” This became known as the Laurel Hill Cemetery, which is “the property of the Inhabitants of Deerfield.” The by-laws of the Deerfield Cemetery Association updated in 1967 state that, since the land is the property of the people of Deerfield, no deed for a lot can be given, but instead the Association shall give a lease in perpetuum. The rental shall be $100 for residents of the Town of Deerfield and $200 for non-residents. Such rental shall include perpetual care. The Board of Directors of the Association laid down some rules:

- The above prices are for standard-size lots – others to be established by the Board

- Trees, shrubs, etc. must be approved by the Board

- No fences or railings around lots

- No tombs

- Right to place stones, monuments, memorials subject to approval of Board

and further, that if any monument, effigy, or any structure whatever or any inscription shall be determined by the Board to be offensive or improper, that the Board shall have the right to, and it shall be their duty to enter upon said lot and remove the offensive or improper object or inscription, after a conference with the lessee of the lot. [Discuss the difference in the number of rules between the two burying yards and how it reflects society in general.] Was society in general becoming more complex? Does an increased population demand that more rules and regulations be imposed upon the citizens of that society?

In the time of the colonial revival, beginning in the 1870s¸ interest in beautifying public spaces began to emerge. Rural cemeteries became picturesque gathering places for family outings where people took delight in the sobering influences of the presence of death. Aided by melancholy writers in the style of Hawthorne and Poe and by the paeans to nature published by Thoreau and William Cullen Bryant, the public created a popular culture centered on the sentimentalization or “domestication” of death and people were stirred by ruins or monuments set in a place of nature.

As there were changes in the attention paid to the landscaping of public spaces, like burying yards or the newly designated cemeteries, there were also changes in the rituals attached to dying. Before the Civil War, the care of the dead was largely the domain of the deceased’s family and neighbors. The corpse was customarily laid out on a board that was draped with a sheet and supported by chairs at either end. The body was washed, almost always by a female member of the household, and wrapped in a sheet for burial. A local carpenter or furniture maker (in Deerfield, the coffin maker was a wheelright named John Death, until he changed his last name to Dickinson), supplied a coffin, a simple pine box with a lid. The undertaker, often the same carpenter or furniture maker, or perhaps the owner of the local livery stable, took the coffin to the house and placed the body inside. With the family and friends gathered around, the minister performed the appropriate religious rituals, and then the undertaker conveyed the coffin to the graveyard.

Around the time of the Civil War, embalming gained wider use in order to preserve the corpses of the dead soldiers whose families wanted them shipped back home, sometimes a considerable distance. Embalming was not a new nor a mysterious art – its practice dated back to ancient Egypt – but the Puritans regarded it as distasteful and unnatural. This began to change with the death of Abraham Lincoln. In order to make the long, slow journey by train from Washington, D.C. to Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln’s body had to be embalmed. The marvelous effects of embalming were witnessed by the huge audience that gathered along the train route of Lincoln’s funeral procession. His body was displayed, not in a simple pine box, but in an ornate mahogany casket – now the more preferred term for coffin – with silver-plated hardware and a silk-draped interior.

This set a new standard in the business of dying. By the late-nineteenth century, caring for the dead had become a business. Embalming, promoted as a public-health measure, now took place in a funeral home rather than in the home of the deceased. Casket-makers offered a variety of choices to an increasingly prosperous public as undertakers banded together in 1882 to create the National Funeral Directors Association.

When you walk through an old graveyard in your hometown or in your travels, think about what has made it look the way it does: attitudes toward death and attitudes towards beautification of the landscape. Take note especially of the inscriptions on the upright stones set in fence-enclosed spaces kept trimmed by young livestock. The outdoor art and nature museums of the late nineteenth century – Mount Auburn Cemetery in Boston is a fine example – were devoted to elaborate memorials to the past and to nature. Compare and contrast them with the late twentieth-century’s “burial garden” with closely trimmed grass, ornamental plantings, and artificial flowers, the markers an almost insignificant adjunct – small, flat, uniform, and embedded for the ease of the mowing machines. What is the message?