by David Proper

In 1786, 90 percent of the nearly 3.5 million Americans, were farmers. They formed the heart of the Continental Army that defeated the British to secure political freedom. During the war, the military was a willing buyer, and farmers had a good market for their products. Later, in order to pay the state’s portion of the costs of the Revolutionary War, taxes were levied on landowners throughout the new United States. In Massachusetts, the merchants in the eastern part of the state, who no longer enjoyed the protection and trading ties with the British (especially the lucrative trade in the West Indies), had to be repaid in hard currency to remain solvent. They demanded payment from the small shopkeepers, payment that was not available.

These farmers, many of whom had been soldiers in the Revolutionary War, were paid in scrip, generated by the state. The state never intended the scrip to be redeemed at face value, but these men used it to pay off their debts until the merchants and storekeepers would no longer accept it because of its plummeting value. A few of the wealthy bought up the scrip as an investment, expecting that the value would be increased. As the value of the scrip declined however, many were affected. Later, the state voted to accept scrip at an increased value.

Since the farmers could not produce the necessary cash for goods and taxes, land was taken then sold at auction to satisfy the creditors, sometimes for as little as 1/3 its value. To assume the land as payment, the courts met throughout the state to act. Throughout New England former Revolutionary officers were often looked to for leadership. They reasoned that if the courts did not meet, no cases could be heard, no suits prosecuted, and no foreclosures could be handed down. Led by Daniel Shays, the rebellious yeomen in Western Massachusetts (the “regulators”) proceeded to shut down the courts to prevent them from acting on the disposition of their land.

In 1786, 1,500 men, in what is now called Shays’ Rebellion, took possession of the Northampton courthouse. Disillusioned by the perceived failure of the government to recognize their efforts to gain liberty, these men later marched to Springfield to gain control of the weapons owned by the Federal Government in the arsenal there.

Mindful of the discontent in the western part of the state and unable to raise a militia at the state level to control the outbreak, the eastern merchants and magistrates underwrote the cost of an army led by General Lincoln. Because of poor communication within the faction led by Shays the plan for three groups of men to meet at the Armory failed. Lincoln’s militia was able to reach the armory before them, turning the cannon on the men, killing three and scattering the rest. Many moved their families north to New Hampshire and Vermont, and New York.

The Aftermath:

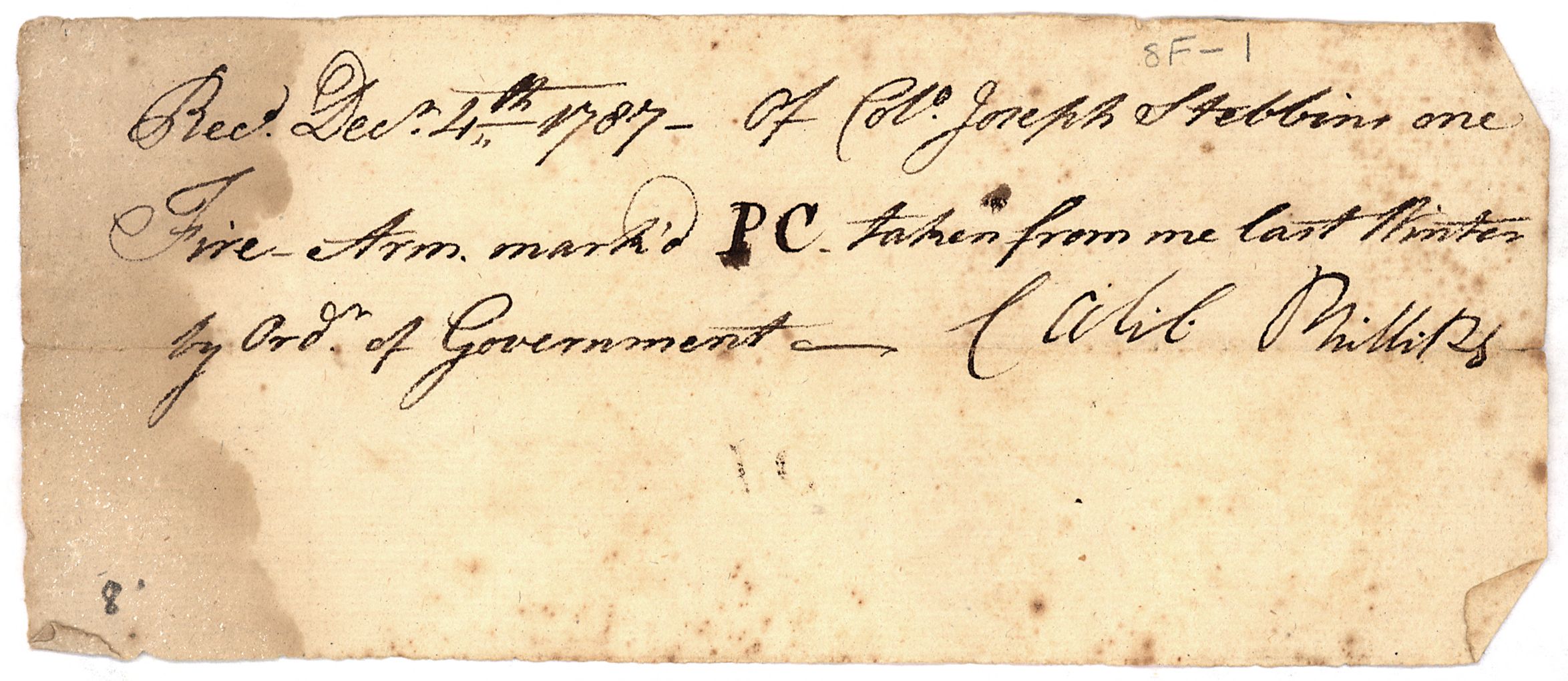

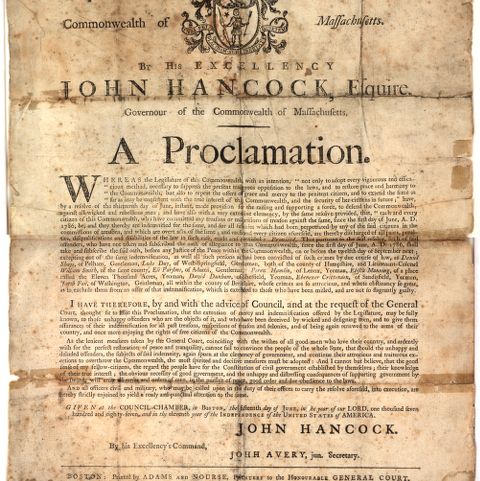

After the rebellion, men were asked to recant and turn in their guns, signing an oath that for three years they would not vote, or hold office, teach, or run a tavern. Although the oaths were taken, little effort was made to enforce them. Shays moved to Vermont, took the oath of allegiance, and was granted a pension by the nation. He died impoverished in Sparta, New York.

The Impact of the Rebellion:

The event occurred in a time when society was in dramatic transition. Some people felt the national government’s constitution rescued the republic from possible anarchy portended by Shays, while others thought of the protests as exercise of “the true democratic spirit by the common folk.”

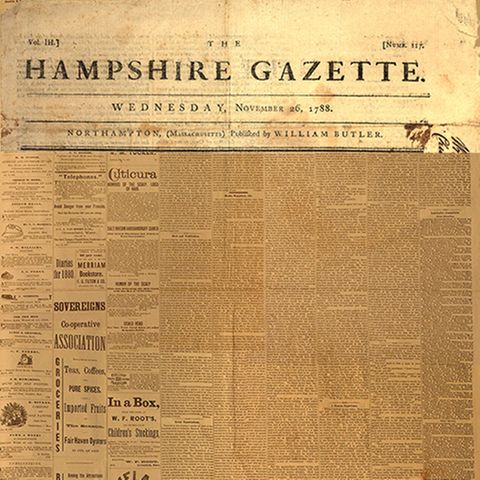

Shays’ Rebellion had implications beyond the state level. Other states had similar issues regarding taxation, scrip, and discontent. At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, it was decided that the Federal Government would assume all state debts incurred to fight the Revolution. The clause “to ensure domestic tranquility” and the words “Commander-in-Chief” were added to the Constitution. The vote for constitutional ratification in Massachusetts in 1788 was 187-168. It was split roughly the same as the opponents of Shays’ Rebellion. Those against were largely in the west for fear of oppression or discontent. Those in favor were mostly in the east, perhaps because it would provide for unified trade agreements.