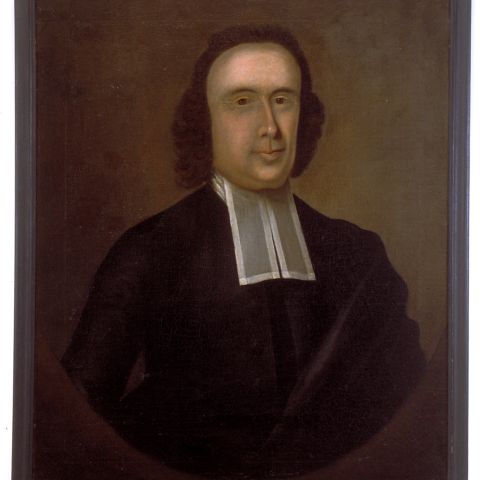

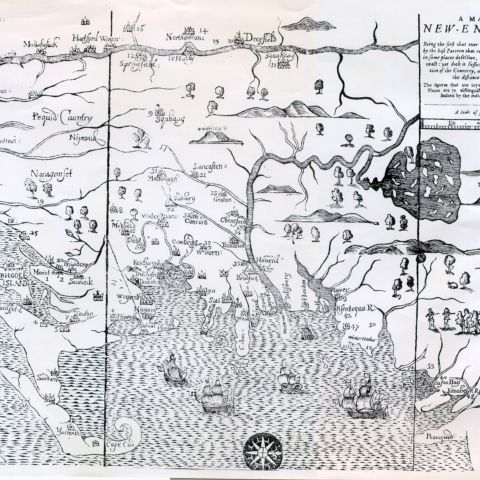

The Spanish, Portuguese and French dominated early exploration and trade in North and South America. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, the English colonies had more than made up for lost time. Their success in attracting settlers was unmatched. From the earliest period of colonization at the turn of the seventeenth century until 1760, as many as 700,000 British men, women and children left the Old World for the New. Social, economic and political developments in the seventeenth century lay behind this unprecedented movement. High rents, periodic food shortages, civil war, and diminishing opportunities pushed some people toward the colonies, while dreams of prosperity drew others. Persecution or the fear of persecution for religious or political reasons induced still others to leave their homeland. And, by 1619, the first involuntary African immigrants arrived in the colonies and were present in the Massachusetts Bay Colony by 1638. Developing from frontier outposts into thriving provinces was not without growing pains. Religious disputes, economic crises, and political unrest characterized colonial life at the end of the eighteenth century. Much of this tension grew out of the colonial experience itself. Most people believed, like the New England minister Jonathan Edwards, that every person had an “Appointed office, place and station, according to their several capacities and talents, and everyone keeps his place, and continues in his proper business.” In reality, the colonies could not recreate the elaborate hierarchy of wealth and status that structured English society. Through it all, successive waves of newcomers continued to play a critical role in creating, defining and redefining colonial society.

Turn of the Century: 1680 – 1720

Details

| Topic | Immigration |

| Era | Colonial settlement, 1620–1762 |