NM: Now, when did you enlist?

RL: Uh…it was done in 1945. I think they opened it up…and…

NM: So you had not enlisted during World War Two, but you enlisted at the end? Or…

RL: No, it was, it was at the …it was about the end of the thing, ’cause they had built Westover field for that Second World War, you know, out there. And, … I’ll never forget when they built it, we thought it was just gonna be for soldiers and we got notices sent to our churches, asking…they were going to have a pick–up system in Springfield, where they pick up young women that were eligible, eighteen years old and over, to go out to dance with the young men, because some of’em had to stay over the…overnight before they were shipped out overseas. And they wanted to have entertainment. That was before there was a USO, but it became the USO around the nation, and that…uh, they opened up these clubs on the …areas where the …troops were at …I remember the first time going with a group…about fifty girls from Springfield, and … we were just as bashful as those young men were. They were being awful careful. We…saying, oh brother. But, uh, dancing got us together …

NM: Did you dance as a performance, do you mean? Or…

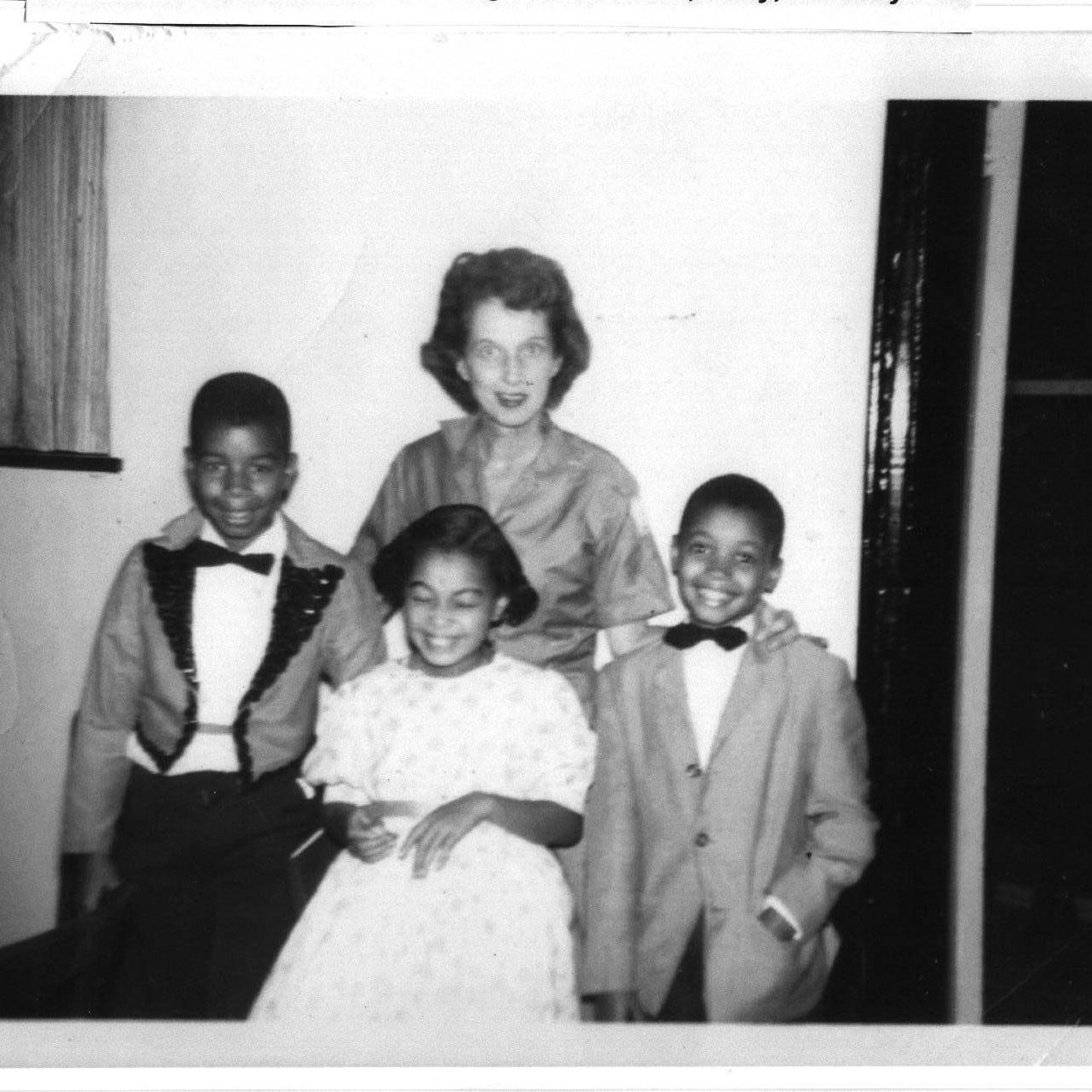

RL: No, no. Dancing. You were girls going there to be friends with the soldiers who would be there overnight, stationed overnight, or during the week, or workers who worked there. There were thousands of them coming in. And they would…they just didn’t want the young men just to come in and sit in there…in the lounges, with no activity going on. And they were trying to figure out how to …let them stay overnight, and yet enjoy what they were doing before they got in…I guess….that, there, uh, unhappy… situation by being a part of the war, you understand. And they asked for volunteer girls, out of the churches first, and then you had to have an age group…belong to a group, and they sent busses in from Westover field to pick you up, either at the churches, or clubs, uh…community centers here. And there…it ended up you had maybe …eight or nine hundred girls out there. That’s a lot of people filling up that big club out there. And, …we went out there and …that activity was very exciting. Uh, I sang, of course, because I …I volunteered with the USO for the simple reason that I…they wanted singers in the trains from the city, and um…I volunteered, and…my children were known as the Loving Trio. The boys tap danced. Holly was a ballet dancer.

NM: Now these were your children.

RL: Those were my children. And they were called the Loving Trio, and they became a part of the USO circuit, as I did, for about six years there at Westover field, to do the entertaining on a regular basis. … I remember one particular…each of us…of the children had their own… costumes and things, and I remember one night, …my husband had given my sh…beautiful silver shoes…to Tony, that’s the middle boy, ’cause I had three children. And when we got up there, it w…was a November night, snow, and et cetera. I have … Artics on, and so forth. And I looked around and I says to him…we were going to change up, to get started, and I says, T…okay, Tony, where’s the shoes? And he’s lookin’ at me. And I thought he had it. And I said, wh…wh…where’s the bag with my shoes in it? He says, home. And there we are… …I said, what d’ya mean home? [chuckles] My husband Minor looked him and says, where is it? ‘Cause he was about…then he was about nine, ten years old. And he says, he forgot it. He…he…what he had…his costume, you know… to…[big sigh] Okay. So, in the Artics and the evening gown, we performed.

NM: Artics…

RL: That’s another picture. I didn’t bring it, but I have a picture of me in those Artics and that…evening gown and I…they thought it was part of the act! And uh, I didn’t think it was part of the act! But these are some of the cute little things that happened that … we as a family, we enjoyed going out there and…going up to Rhode Island sometimes, we went up to… USO in Rhode Island, … where they had some of the …planes station up there….

NM: Now, when you were going out to Westover, was that before you were married, or you were…

RL: Oh no! We were married. We were married, oh yeah. We were married…as I say, Holly must’ve been about, uh, seven. Tony, at the time, must’ve been about uh, eight. Tony…Butch…they’s known as the Loving Trio. And the idea is that they were going so much with me that…and they were doing their own dancing …with being called by the studio they took lessons from, and they, uh…’scuse me… [Tissue break]

NM: Sure…

RL: …they automatically got used to people, and entertaining, so they had their own… dance… routines themselves that [the]…studio the children were out of, were taught, and they were able to be quiet, because they were quite a site to see, youngsters like…that young, and… it was something that I enjoyed because I was an older person, knew where the kids…working with me…and my husband, and we had quite a year doing that.