In the years between the American Revolution and the Civil War, the American home and family exhibited both change and continuum. Rapid changes were quickly stamping out ways of life that had endured for generations, and nostalgia for a vanishing past was discovered as a soothing, if not entirely effective, way to slow down the acceleration of life.

Christopher Clark, in his book The Roots of Rural Capitalism, points out that the men who went to fight in the two wars, the American Revolution and the Civil War, did so under very different conditions, illustrating the extent of rural social change in the intervening decades. Eighteenth-century soldiers were recruited from a household economy that required them to labor on farms as well as to fight. Their vital role in production made colonial and Revolutionary militiamen notorious for preferring short-term enlistments, and for being reluctant to remain far from home for long periods. To conduct the Revolutionary War, Congress came to rely heavily on a continental army recruited from among the young, the poor, and the marginal, for whom fighting conflicted less with other pressing obligations.

[By the Civil War, times were different. Massachusetts farm laborers, mechanics, factory operatives, and clerks enlisted in such substantial numbers and were prepared to serve for considerable periods, hundreds or even thousands of miles from their homes. Population growth, immigration, and the emergence of a wage-labor market had made individual young men less essential to the survival of the rural economy. They could be replaced at their work, or could — if their families had means — even buy substitutes for military service.]

America, unlike Europe, was still pretty much pre-industrial and its smoke-free and sun-filled atmosphere, characterized by clear, clean air, was described as invigorating. The cities, in particular, were characterized by freshly painted wooden houses and buildings made of brick in response to the devastation of serious fires. Much was still produced at home, but was supplemented by store-bought goods. Shops proliferated in cities and villages as ambitious manufacturers, ever-expanding trade routes, and better transportation supplied more products for a growing market, and enriched American parlors with a profusion of objects. James Fenimore Cooper remarked in 1828 that, “The whole world contributes to their luxury.”

One must, however, avoid rampant nostalgia for the past and remember that many images, paintings, or drawings in the days before photography, idealize the “old days.” It is important to remind ourselves that much of what was recorded was what someone liked in places where people were happy. The end result is often one of charm and nostalgia, and bears little link with the truth of history.

It is generally conceded that Philadelphia was the tidiest city in America and that filthy streets were common in most other large cities. In New York City, a law was passed as early as 1731 prohibiting the disposal of carrion or filth in the streets, and further stipulating that the inhabitants “rake and sweep together all the dirt, filth, and soil lying in the streets before their respective dwelling- houses, upon heaps, and on the same day or on the Saturday following, shall cause the same to be carried away and thrown in to the river, or some other convenient place.” The street filth was so pronounced that, by 1800, professional carters had been hired to take up refuse in Manhattan two or three times each week.

The horses that pulled all conveyances, in the days before the automobile, contributed to the smells of American cities and towns, as did the loose pigs that ate the garbage and the pools of stagnant water owed to inadequate drainage. Near the common in the town of Deerfield existed a “nuisance,” a drainage problem directly related to a meander of the Deerfield River across the main street. Adequate sanitation, in addition to drainage, was a problem in villages and cities, but was more noticeable where the population was larger.

As the 18th century advanced and fuel supplies dwindled in quantity even as they rose in cost, the large kitchen fireplace was scaled down. By the 1820s, it was often replaced by iron cook stoves. (Note: By the mid-century cookbooks included receipts for both open hearth and iron stove cooking.)

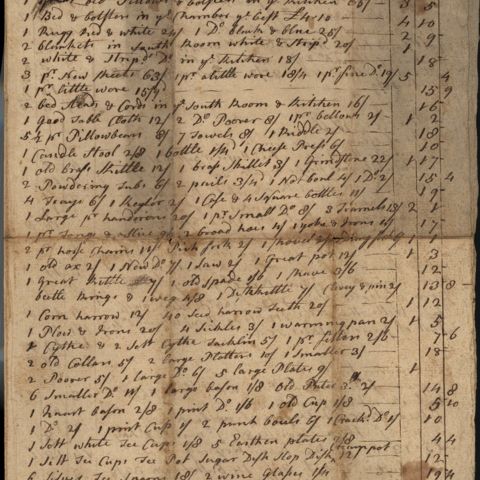

Specialized cooking was accompanied by specialized rooms and furniture forms. The dining room, popular after about 1800, was often fitted with a sideboard, a new form intended to store and display the array of dishes from England and China. Often two parlors, one aloof and ceremonial and the other informal, were visible on either side of a center hallway or entry. Closets were often included in the plans for new houses to accommodate the burgeoning list of possessions. Furniture was displayed around the walls, to be moved into less formal positions when in use and then returned. The card table that spent most of its life against the wall could be doubled in size by swinging the back leg out to receive the hinged leaf on top, accommodated four or more people for cards or board games. The sofa came in vogue around 1770 to augment the bench as a form of multiple seating. Painted furniture, particularly Windsors or fancy chairs, provided brilliant spots of color around the edges of many sitting and dining rooms. By 1800, beds generally disappeared from parlors and were seen mainly in chambers or in downstairs rooms designated as “bedrooms.” Many tabletops were covered with cloth in a variety of materials and the cloths themselves were adorned with a variety of knickknacks, trinkets, books, and lamps. Wool carpets showed up with some frequency in wealthier homes at the end of the 18th century, as did canvas floor cloths, painted, sometimes with elaborate geometric or floral designs. Straw matting from Asia was laid on floors, particularly in summer months. Wallpapers, which before 1750 were imported, were being produced in this country in some abundance soon after the Revolution.

As window glass became more easily produced and less expensive, windows became larger overall and the individual panes increased in size. Although few windows were dressed with fabric in the 17th and early 18th centuries, during the late 18th century more houses began to display curtains.

The fabrics used for domestic purposes, whether window curtains, tablecloths, or clothing were sure to be a miscellany of homespun and factory-produced goods. Although cloth produced in the New England textile mills was available to residents in city and country, and many young women from New England’s farms and villages were enlisted to work in the mills, textile production remained very much a part of rural life far into the nineteenth century. Substitution of store-bought for home-produced cloth did not end independent household manufacture, but often merely pushed the most important part of it one stage along in the production process. Where spinning and, to a lesser degree, weaving had once occupied women’s time, sewing became a common activity for them, both for home consumption as well as for sale.

Thousands of families migrated to the expanding West after the American Revolution, as thousands more moved from the land to the growing cities and towns. Farmers and craftsmen, who two generations before had lived mainly in a world of independent producers, now faced larger, competitive markets, greater social distance, and impersonality. As people moved away from their home base, a breakdown occurred in the link between generations, particularly in the field of household chores. Whereas the apprentice system had worked in early New England homes with the mother-daughter-granddaughter chain intact, that learning method was interrupted as younger generations moved to distant homes and could no longer consult with older family members concerning the “art and mystery” of housewifery. A housewife’s duties might encompass the production, preservation, preparation, and presentation of food, and the fabrication of cloth, clothing, candles, and soap. Although these commodities became increasingly available for purchase in the first half of the 19th century, store-bought goods usually supplemented rather than supplanted homemade products. To replace the mother-daughter oral transfer of advice and information, cookbooks and household advice books begin to appear.

As the end of the 18th century advanced ventilation and air circulation, cleanliness became increasingly important and emphasis shifted from genteel politeness to a healthful lung-strengthening airiness. The night air was no longer seen as detrimental, and modest valances and abbreviated head cloths replaced the heavy curtains that had enclosed the beds through the 17th and 18th centuries.

Cleanliness was difficult to achieve in early America, where the streets were muddy and dusty, window screens were absent, water might freeze before a roaring fire, and soap making was often unsuccessful. The first medical school, Queens College (now Columbia University), opened in New York City in 1790, and the medical profession began to promote hygiene as a disease preventive. By the early 19th century, wash stands began to take their places in many bedrooms, fitted with pitcher and basin to facilitate and legitimize regular “washing up.”

Disease, epidemics, and the problems of early death were still present as they had been in the earlier centuries, and continued to contribute to the frequency of remarriage. Parents, stepparents, children, and stepchildren struggled to rethink and rework relationships. It was an ever-present and ongoing effort to achieve harmony and prosperity in a time that held the promise of continuing increased creature comforts in an enlarging and rapidly changing society.