Native American history spans tens of thousands of years and two continents. It is a multifaceted story of dynamic cultures that in turn spawned intricate economic relationships and complex political alliances. Through it all, the relationship of Indigenous peoples to the land has remained a central theme.

Though Native Americans of the region today known as New England share similar languages and cultures, known as Eastern Algonquian, they are not one political or social group. Rather, they comprised and still comprise many sub-groups. For example, the Pequots and Mohegans live in Connecticut, the Wampanoag reside in southeastern Massachusetts, while the Pocumtucks dwelt in the middle Connecticut River Valley near today’s Deerfield, Massachusetts.1

Like those of other Native communities, Algonquian elders have traditionally transmitted important cultural information to the younger generations orally. This knowledge, imparted in the form of stories, includes the group’s history, information on origins, beliefs, and moral lessons. Oral tradition communicates rituals, political tenets, and organizational information. It is a vital element in maintaining the group’s unity and sense of identity.

Creation stories, for example, help to define a sense of how human beings relate to the Creator and to the world. A creation story of the Pocumtucks explains the origin of the Pocumtuck Range, located in present-day Deerfield and Sunderland, Massachusetts. The story tells of a huge lake in which lived a greedy giant beaver. The people complained to the god Hobomok that the beaver was attacking them and consuming all of the local resources, so Hobomok decided to kill it. Following a titanic struggle, Hobomok vanquished the beaver with a club fashioned from an enormous tree. Its body sank into the lake, turned to stone, and formed the Pocumtuck Range.

Such stories and their settings establish the Native American presence from time immemorial by relating how the Creator placed Indigenous peoples in their traditional homelands. These are stable and permanent cultural and physical landscapes where Native nations have lived, and in some cases, continue to live to the present day. (Handsman 13). Creation stories thus reflect the central place their relationship with the land occupies in the culture and history of Native peoples. Certain sites within a homeland might hold special meaning and thus serve as important gathering places or focal points. In the Pocumtuck homeland, Peskeompskut (today known as Turners Falls) served as an important fishing area and meeting ground. Wequamps (Mt. Sugarloaf) is the giant beaver’s head and focal point of the creation story describing the origin of the Pocumtuck Range.

The Connecticut River Valley was a vital crossroads for Native peoples of the Northeast. Today, Deerfield lies at the heart of the Pocumtuck people’s homeland. They were part of a network of Algonquian communities in the middle Connecticut River Valley that lined the river. In addition to the Pocumtuck, the Norwottuck homeland lay near present-day Northampton and Hadley, the Sokokis near Northfield, the Agawams around Agawam, the Woronocos near West Springfield, and the Nipmuc homeland lay in central Massachusetts. These peoples were linked culturally, linguistically, politically, and through kinship.

These Algonquian communities together constituted a formidable power in Southern New England (Melvoin 32). Numerous trails and waterways connected settlements with each other, facilitating intricate and extensive trade networks. Algonquians also traded with other peoples living to the west, north and south. The fertile soil and plentiful game fostered a prosperous society that enjoyed a robust economy and a stable political structure.

Eastern Algonquian people resided in different parts of their homeland at different times according to their needs. (Handsman 13). They often lived in smaller groupings connected by a network of trails or waterways. Environmental rhythms, kinship networks and ceremonial requirements together formed a calendar that regulated their movements. For example, a group might move to a location nearby to clear new land for their fields once their current ones became exhausted. They also often located near good hunting or fishing areas. Groups at times might break up into smaller family units that would leave a village to hunt in other parts of their homeland. People also relocated to more protected areas with the colder weather.2

Agriculture flourished in the milder climate of Southern New England, supporting larger concentrations of Native peoples than the harsher northern region. Archaeological evidence suggests that Indigenous peoples of Southern New England (Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island) began growing corn over one thousand years ago. In addition to this staple, they cultivated many other plants, including beans, squash, Jerusalem artichoke, and tobacco. The shorter growing season of Northern New England led Algonquians living in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine to trade with groups to the south to supplement their food supply.

Like their counterparts in many Native nations throughout the continent, Algonquian women worked together to cultivate common fields, as well as harvesting, preserving and preparing food. They also helped to construct their homes and produced many household accessories. Algonquian men hunted, fished, made tools and protected their communities. Working communally and dividing responsibilities along age and gender lines enabled Native groups to accomplish necessary tasks such as building canoes and homes. Significantly, a good deal of children’s work and play revolved around activities that helped them to develop the communal and physical skills they would need as adults. Such activities included keeping crows out of the cornfields and gathering nuts and berries.

Sustained contact with Europeans beginning in the 15th century subjected lifeways established over centuries or even millennia to severe stress. Native Americans have struggled over the last several centuries to retain and sustain their relationship with the land in the face of changing economic relations, rapidly changing political alliances, demographic catastrophe, and warfare.

Much of the early contact between Europeans and Native peoples revolved around trade. By 1600, French, Dutch, and English traders frequented the northeast coast of North America trading metal, glass, and cloth for animal pelts, especially beaver. A reciprocity-based system of exchange characterized initial trade relations. Successful trade depended on good relationships between traders and Native groups. These practices superficially resembled pre-existing exchange patterns among area Native peoples. It quickly became apparent, however, that these new relationships did not really replicate traditional trading practices. They lacked the social and cultural assumptions that provided structure and meaning to the old exchange patterns.

The presence and agenda of these new trading partners generated far-reaching consequences. Native groups heavily involved in trade with Europeans altered their living patterns to better position themselves to deal with the newcomers. That trade placed disproportionate attention on hunting for lucrative beaver pelts in place of traditional subsistence hunting. Native traders became increasingly reliant on European trade goods, adapting them to their own traditional uses. Competition among groups for a rapidly diminishing beaver population increased. The power balance shifted in favor of groups and individuals with connections to traders and European goods (Salisbury 57).

Trade with Europeans generated demographic as well as economic and political consequences. Native people used preexisting trade routes and communications networks to acquire the beaver pelts European traders prized. They received in exchange desirable goods such as textiles, various metals, and firearms. In this way, European traders’ goods penetrated far into inland North America. Old World diseases traveled with those goods, triggering what one historian has termed a “demographic catastrophe.” Before European contact, the peoples of the Western Hemisphere lived isolated from many Old World diseases. They thus did not develop immunities to diseases such as measles and smallpox that plagued other parts of the world. European contact through trading set off widespread epidemics. Old World diseases reduced Native populations in some areas by up to ninety percent. (Salisbury 23, 25). The cultural consequences of this demographic disaster were no less devastating than its economic or political effects. Astoundingly high mortality rates seriously compromised the oral transmission of collective wisdom and culture.

Early and seemingly limited coastal trade contacts with Europeans thus weakened and depopulated many Native nations years before European settlers arrived. English settlers arriving in Massachusetts by 1620, brought another element into Native/European relations: colonization. As with earlier trading ventures, the companies that funded colonizing ventures like that at Plymouth, Massachusetts, also sought to establish lucrative trade relations with Native peoples. At the same time, English assumptions surrounding colonization introduced a new and ultimately incompatible component into European/Native relations. Unlike individual traders, English families came to establish communities and settle permanently on Native lands. The relatively positive relations that characterized early trade between Europeans and Native Americans quickly deteriorated. Cultural clashes and disputes over land escalated as English towns grew and population pressures intensified colonists’ demand for more land.

The English settlement of Springfield, Massachusetts, is an example of how first European trade and then settlement affected pre-existing Native American trade networks and political relations. Settled in 1636, Springfield was the first English settlement in the middle Connecticut River Valley. William Pynchon and his son John quickly established a lucrative fur trade with local Native peoples whose hunters traded furs for European products, while the English sold these furs back to England for high profits. By the 1650s, however, hunters had exhausted the fur supply of the region. Tensions between Native communities flared into open hostility as hunters traveled further into territories outside their homelands to find beavers. Warfare in 1664, between the Kanien’kehaka (Mohawks) of the Haudenosaunee from Eastern New York and the Pocumtucks pushed many Pocumtucks from the central area of their homeland.

When they could no longer supply beaver furs to European traders, Native people lost bargaining power and trading leverage. Land became the only resource Europeans were willing to accept in payment for their goods and to pay off debts accumulated through the English credit system. Land sales escalated and English towns began to line the Massachusetts portion of the Connecticut River between 1636 and 1685.

The ideological reasoning of the English who displaced Native Americans from their homelands reveals the radically different and ultimately irreconcilable worldviews of these two societies. English settlers viewed the land as a wilderness void of civilization. Where the English saw “virgin land”, they also saw God’s mandate to appropriate and “civilize” it. John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts, explained the right of the English to take Indigenous land by claiming “[t]hat which is common to all is proper to none. This savage people ruleth over many lands without title or property; for they enclose no ground, neither have they cattle to maintain it, but remove their dwellings as they have occasion, or as they can prevail against their neighbors” (quoted in Melvoin 54).

Native American movement through their homelands was a sophisticated response to the change of seasons and the location of natural resources. In contrast, English society had evolved over centuries a sedentary agrarian culture and an economy based upon individual land ownership. For English people in this period, private ownership and permanent villages were evidence of true and appropriate land use. From their perspective, “New World” land appeared to be empty (Calloway 53). With only rare exceptions, most English people could not recognize the way in which Native peoples used their land in accordance with their needs, cultures, and belief systems.

In Native societies, land was home and communally held. People could not alienate it any more than they could sell air or water. In contrast, individual land ownership conferred wealth and status in European societies. It was a commodity that could indeed be bought and sold. Having never before “sold” land, Native peoples in the Connecticut River Valley may not have initially understood the European interpretation and consequences of land transactions (Melvoin 18).

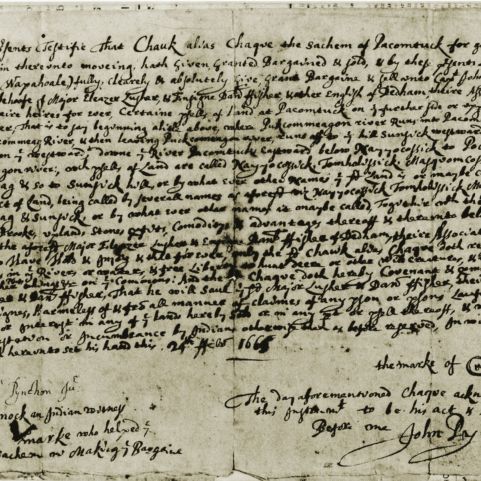

Whether or not Native leaders could or intended to sell land to the English is debatable. Sachems were Native American leaders who commanded considerable religious and economic authority over a community. Evidence exists that some sachems dispensed land use rights to various tribal members and negotiated treaties with other groups. To alienate land completely, however, may have been beyond the authority of any one individual. Some of the language in early deeds suggests that Native representatives viewed the agreement as a traditional transfer of land use. That is, in the first sales, Native peoples acted as though they were selling use-rights, but not absolute ownership of the land itself.

For example, in 1671, soon after the Pocumtuck conflict with the Kanien’kehaka, Springfield land broker and trader John Pynchon brought land proprietors from Dedham (outside of Boston.) These proprietors purchased, surveyed, and laid out part of the Pocumtuck homeland for a new English town. The events and the language surrounding this land transaction reveal just how great was the cultural impasse between the English and the Native Americans on this issue. The sachem Chauk was not Pocumtuck, but somehow was chosen by either the English or the Pocumtuck people to reserve Pocumtuck rights to hunt, fish, plant, and gather wood on the very land he was “selling.” As in other early deeds, the document included clauses enabling Native peoples to retain use of and contact with their ancestral lands. The language of this and other early deeds suggests that what Indigenous peoples believed they were selling to English settlers was the right to plant and set up their homes (Spady 24) on that land.

As time passed, the English definition of land ownership overwhelmed Native interests and interpretations. Towns and settlers increasingly enforced their legal understanding of the deeds as transferring to them an exclusive right to the land. New landowners accordingly sought to prevent Native “trespassers.” Such interpretations forced Indigenous groups to adapt to English life-ways in order to remain in homelands where English had built towns.

The rapid decline of the fur trade and English geographic expansion heightened tensions between Native peoples and European settlers. Up and down the valley, unhealthy patterns of unequal and discriminatory relations intensified between English communities and displaced Native peoples (Bourne 135). Colonial governments fined Indigenous peoples for breaking Puritan religious laws such as traveling on the Christian Sabbath. The English further strained relations by selling Native prisoners into slavery or forcing captured Native children to work as farm laborers (Trumbell 173). The law afforded some protections to Indigenous people only so long as they conformed to European standards and lifestyles such as dressing like Europeans and cutting their hair (Sheldon 73).

Native Americans throughout New England experienced removal and restriction from their land and the mandated compliance to English laws and culture. Mistrust, resentment, and anger grew. In 1675, armed conflict broke out in the east among the Wampanoag of Southeastern Massachusetts. Other Native groups quickly followed suit.

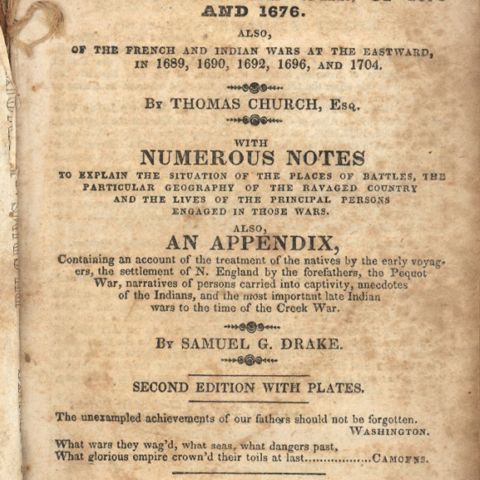

The uprising that became known as Metacom’s War, or King Philip’s War, involved over 11,000 allies from Native communities on both sides of Narragansett Bay (in Southeast Massachusetts and Rhode Island) northwest through Central Massachusetts to the Connecticut River Valley (Melvoin 121).

The war produced terror and tragedy on both sides. Thousands of colonists and Indigenous peoples met terrible deaths. Both sides killed defenseless men, women, and children. New Englanders lived in a constant state of terror for the next one and a half years. It seemed as though only a few seacoast cities would survive. Panic-stricken colonists abandoned outlying farms and settlements and crowded into garrisons. In September 1675, Native American forces ambushed a convoy of farmers from Deerfield escorted by soldiers from Eastern Massachusetts transporting grain south for safekeeping. Sixty men died in what became known as “The Bloody Brook Massacre.”

Meanwhile, Native Americans in Southern New England suffered devastating losses. On May 18, 1676, Captain William Turner led a surprise dawn attack on Peskeompskut (Turner’s Falls) on the Connecticut River in Massachusetts. Approximately 300 Pocumtuck, Norwottuck, Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Nipmuc people were encamped on the falls building up food supplies after a winter of near starvation. Over 240 mostly unarmed Native women, children, and the elderly died in this attack (Melvoin 115). Their men were elsewhere, unaware of the attack and unable to defend their families. The English renamed the falls to commemorate what was, to them, a notable victory. The slaughter at Peskeompskut demoralized Native peoples and greatly weakened their resistance. Lost battles in the spring, disease, and impending starvation brought Metacom’s War to a virtual halt. The Native attempt to push English settlement off their homelands in Southern New England dissolved in 1676.

As overt Indigenous resistance collapsed, the English began to “round up the hostile Indians,” executing some and selling others into slavery in the West Indies. The Pocumtucks, Sokokis, Norwottucks, and Agawams of the middle Connecticut River Valley could no longer live safely in their homelands. Although some stayed, most fled for their lives. Some took refuge in the Mahican community of Schaghticoke, outside of Albany, New York (Day 20).

Other groups eventually followed their Abenaki and Sokoki allies to live at Odanak (St. Francis) in Quebec, Canada. Odanak had not yet become a French Jesuit mission when it began welcoming Native peoples fleeing from the aftereffects of King Philip’s War. Pocumtucks, Norwottucks, Sokokis, and Pennacooks (Haefeli and Sweeney 14) were among the refugees. This mixture of peoples at Odanak eventually took on a “Western Abenaki” identity, since the Abenaki from what is now Vermont and New Hampshire once formed a majority of the population. Still other Connecticut River Valley Native peoples joined allies at Pennacook in New Hampshire and Maine, where forceful resistance continued (Day 21).

As people from different groups came to Odanak and Schaghticoke to live, they maintained close relationships with kin that had relocated to other refugee communities. The persecution and loss these exiles had experienced at English hands kept resentment alive. These shared resentments contributed to the willingness among northern communities to participate with the French in future wars against the English.

In the years following Metacom’s War, the Connecticut River Valley remained a crossroads for Native peoples of the Northeast. The former Native residents, though living largely in New York and Quebec, maintained their connection to their ancestral lands. Schaghticoke, Odanak, and Pennecook became a triangle of interactions (Day 23). Deerfield, lying on the northwest edge of English settlement in New England, was on a common path that formed the middle ground between New England and New France (Canada). That there remained no permanently settled Native American communities fed a popular misconception among European residents that the Indigenous peoples of this region had “disappeared.” In fact, they remained. They were living in the area, visiting friends and families who stayed in the valley, hunting in their traditional lands, trading with the English settlers, and passing through on the way to other villages. In this way, Native peoples maintained their connection with their homelands, a connection that persists to the present day.

Endnotes

1Current scientific interpretations of geologic and archaeological evidence postulate that the first people in North America migrated from Asia sometime during the last Ice Age via the subcontinent of Berengia. Most archaeologists and anthropologists date the earliest known human presence in New England no earlier than about 12,000 years ago.

2According to archaeologist Russ Handsman “[a]lthough Native peoples moved around homelands according to daily, seasonal, and ceremonial calendars, and between homelands to visit kin, they did not abandon or desert these places until forced to leave by the actions and prejudices of others. Even then, their removal was neither complete nor irreversible.”

Bibliography

Bourne, Russell. The Red King’s Rebellion: Racial Politics in New England, 1675-1678. New York: Atheneum, 1990.

Bragdon, Kathleen J. Native People of Southern New England, 1500-1650. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Calloway, Colin. The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600-1800: War, Migration, and the Survival of an Indian People. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990.

Day, Gordon. The Identity of the Saint Francis Indians. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1981.

Melvoin, Richard. New England Outpost: War and Society in Colonial Deerfield. New York: W. W. Norton, 1989.

Handsman, Russell G. “Illuminating History’s Silences in the ‘Pioneer Valley,’” in Native Peoples and Museums in the Connecticut River Valley: A Guide for Learning. Northampton: Historic Northampton, 1992.

Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Sheldon, George. A History of Deerfield, Massachusetts. Deerfield, MA: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, 1895.

Spady, James. “In the Midst of the River: Leadership, Trade, and Politics among the Native Peoples,” unpublished honors thesis, Amherst College, 1994.

Sweeney, Kevin M. and Evan Haefeli. “Revisiting The Redeemed Captive: New Perspectives on the 1704 Attack on Deerfield,” in The William and Mary Quarterly. vol. LII, no. 1, January 1995, pp. 3-47.

Thomas, Peter. “Bridging the Cultural Gap: Indian/White Relations,” in Early Settlement in the Connecticut Valley: A Colloquium at Historic Deerfield. Deerfield, MA: Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State College, 1984.

Education Program Bibliography (12/99) For Teachers:

Atherton, Mary Kay, et. al., Touch With Your Eyes, Orinda Art Council, CA, 1982.

Bracken, Jeanne M., Life in the American Colonies, Discovery Enterprises, MA, 1995.

Calloway, Colin, After King Philip’s War, Univ. Press of New England, NH, 1997.

Carlson, Richard G., Rooted Like the Ash Trees, Eagle Wing Press, CT, 1997.

Carrollton Press, The Laws of New England to the Year 1700, 1991.

Coleman, Emma L., New England Captives Carried to Canada, Southwork Press, ME, 1925.

Cronon, William, Changes in the Land, Hill & Wang, NY, 1983.

Demos, John, The Unredeemed Captive, Knopf, NY 1994.

Dublin Seminar, New England/New France, 1600-1850, Boston Univ., 1989.

Five Colleges Public School Partnership, Native Peoples & Museums in the Connecticut River Valley, Historic Northampton, 1992.

Five Colleges Public School Partnership, Where We Live Teacher’s Source Book, 1996.

Five Colleges Public School Partnership, Adjusting the Lens: Indian Images & Identity, 1997/98.

Flynt, Suzanne, et. al., Gathered & Preserved, PVMA, Deerfield, MA, 1991.

Frakur, Alan, et. al., The Deerfield Reader, American Heritage Custom Pub., NY, 1996.

Historic Deerfield, Inc., Early Settlement in the Connecticut Valley, Historic Deerfield Inc. & Institute for MA Studies, 1984.

Melvoin, Richard, New England Outpost, Norton & Co., NY, 1989.

Proper, David, Lucy Terry Prince, Singer of History, PVMA, Deerfield, MA, 1997.

Sheldon, George, A History of Deerfield, Massachusetts, PVMA, Deerfield, MA, 1895.

Williams, John, The Redeemed Captive of Zion, PVMA, Deerfield, MA, 1987 (1706).

Wiseman, Frederick, The Abenaki People & the Bounty of the Land, Lane Press, VT, 1995.

Wiseman, Frederick, Gift of the Forest: The Abenaki, Bark & Root, Lane Press, VT, 1995

For Students: Non-fiction

Bernstein, Rebecca S. & Jodi Evert, Felicity’s Craft Book, Pleasant Co., WI, 1994.

Bonvillain, Nancy, The Mohawk, Chelsea House, NY, 1991.

Calloway, Colin, The Abenaki, Chelsea House, NY, 1991.

Cobblestone Magazine, Deerfield; A Colonial Perspective, Sept. 1985.

Cobblestone Magazine, Indians of the Northeast Coast, Nov. 1994.

Kalman, Bobbie, Colonial Life, Crabtree Publishing Co., 1992.

Kavasch, Barrie, Earthmaker’s Lodge, Cobblestone, 1994.

McGovern, Ann, If You Lived in Colonial Times, Scholastic, 1964.

Quiri, Patricia R., The Algonquians, Franklin Watts, 1992

Sewall, Marcia, People of the Breaking Day, Atheneaum, NY, 1990.

Shemie, Bonnie, Houses of Bark, Tundra Books, 1990.

Sherrow, Victoria, The Iroquois Indians, Chelsea House, NY, 1992.

Siegel, Beatrice, Indians of the Northeast Woodlands, Walker & Co., NY, 1972.

Waters, Kate, Tapenum’s Day, Scholastic Inc., NY, 1996.

Weinstein-Farson, L., The Wampanoag, Chelsea House, NY, 1988.

Fiction

Bruchac, Joseph, The Arrow Over the Door, Dial Books for Young Readers, NY, 1998.

Bruchac, Joseph, Children of the Longhouse, Dial Books for Young Readers, NY, 1996.

Dalgleish, Alice, The Courage of Sarah Noble, Aladdin Paperbacks, 1954.

Dorris, Michael, Guests, Hyperion Books, 1994.

Durrant, Lynda, Echohawk, Clarion, NY, 1996.

Flower, Kelsey, The Children of Deerfield, Deerfield, MA, 1952.

Hyde, Mathilda, Little Captives of 1704, Olde Deerfield Dolls, Deerfield, MA, 1919 (out of print but available for loan through PVMA).

Osborn, Mary P., Standing in the Light, Scholastic Inc., 1998.

Smith, Mary P. W., The Boy Captive in Canada, PVMA, Deerfield, MA, 1904.

Smith, Mary P.W., The Boy Captive of Old Deerfield, PVMA, Deerfield, MA, 1904.

Speare, Elizabeth, The Sign of the Beaver, Dell Yearling Books, 1983.

Speare, Elizabeth, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, Dell Yearling Books, 1958.

Wilson, Ellen E., Two Paths in the Wilderness, Crane Pub., 1997.