The English who established Deerfield in 1673 were Congregationalists who were descendants of English Puritans. They arrived in New England early in the 17th century in search of economic opportunity and religious freedom. Some of the early Deerfield settlers had lived in towns to the south of Deerfield before settling there.

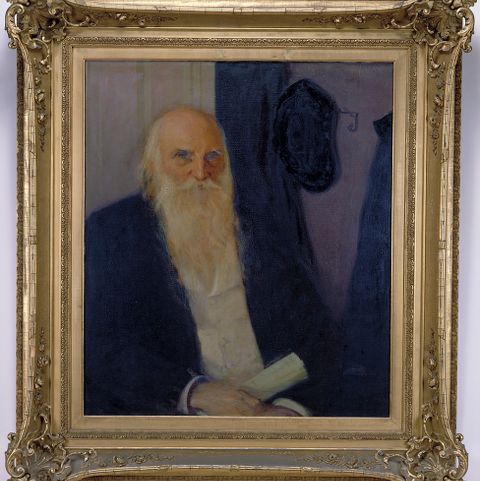

Some of what we know about the lives of Deerfield’s English settlers was learned from George Sheldon, the town’s historian, who lived from 1818 to 1916. He based his conclusions on public records, journals, and family stories. According to Sheldon, the English settlers worked very hard to “bring order out of chaos” by taming the wilderness – they believed that this was what God expected of them. They also had strict beliefs about behavior and believed that idleness was a crime.

Deerfield’s settlers retained a number of customs and beliefs from their ancestors. The Puritans, who derived their name from the word “pure,” aimed to “purify” the English Anglican Church, simplifying services and ridding the Church of its Roman Catholic traces. In the early years of settlement the word “church” referred to the people who attended services, while the buildings were called meetinghouses. These were used for religious services and for town business. The settlers also believed in the absolute truth of the Bible, and put particular stress on the Old Testament.

Each town had a meetinghouse, built large enough to accommodate all members of the community. The most important place in the meetinghouse was the pulpit, which was high and located front and center in the building. There were two floors, but the upper one was a balcony (called a gallery) so that people sitting there could see and hear what was going on. There was no organ until the 1850’s, because the early Congregationalists believed that instrumental music was not appropriate for worship. Reading the Bible was considered extremely important, and it was the principal reason for teaching children and enslaved people to read.

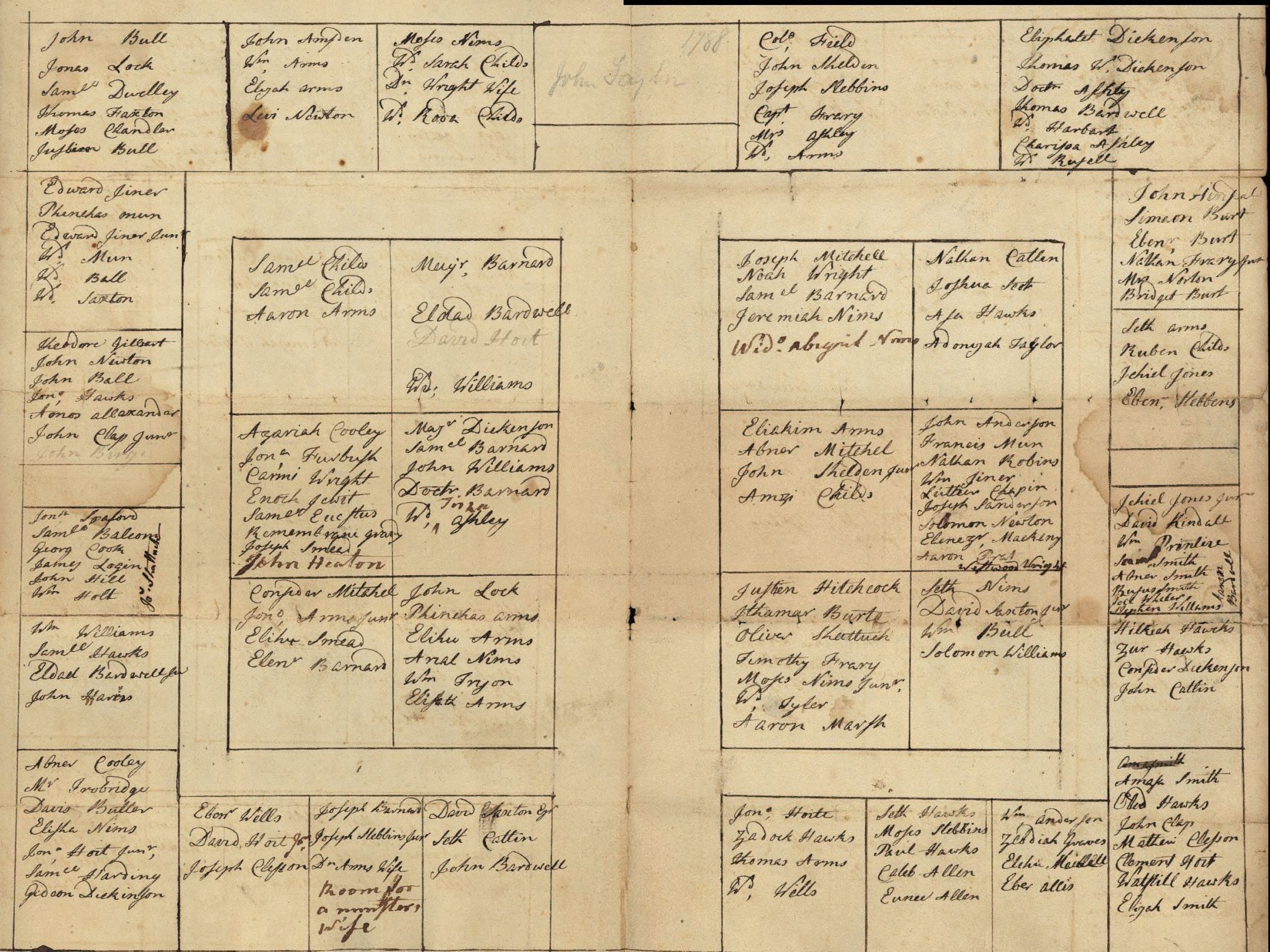

At first, long benches were used, but gradually pews were built and assigned to specific townspeople. Everyone in the village was expected to come to Sunday meeting. The most important people in town had the best pews, the ones nearest the pulpit. The most important people included those who were rich, well-educated, and those who were honored because of age or service to the community. Indigenous people, African Americans, children, and single young people sat in the gallery. The pews were high and enclosed, partly to keep the congregation warm, as the meetinghouse was not heated. There was a committee, elected by the townspeople, who assigned pews. Some seating plans still exist. They help us to get a sense of the social “rank” of individuals and families in Deerfield.

The settlers spent most of their Sundays at the meetinghouse. People brought heated stones or foot warmers to help them stay warm. The Bible was read. The congregation sang psalms (prayers in the form of poetry) to simple tunes without accompaniment. The minister delivered a sermon, which was handwritten and was often used more than once. To make sure that everyone stayed awake during the long services, a “tithing man” walked among the congregation carrying a long pole to prod people who were falling asleep. On Sunday there were services in the morning and in the afternoon. People went home to eat between services if they lived close enough, or (as the town grew) to a tavern for the noonday meal. Town meetings were held four times a year or as needed to settle business.

There was no separation between church and state. All White male heads of households paid for a portion of the minister’s salary. They elected one another to hold rotating offices and formed committees to oversee town business. Committees and positions included (among others) the board of selectmen, the town moderator who ran the meetings, and a fence viewer who made sure the fences were in good order. They also elected committees such as the one to assign seats in the meetinghouse and they appointed the tithing man. Religion was central to their community.