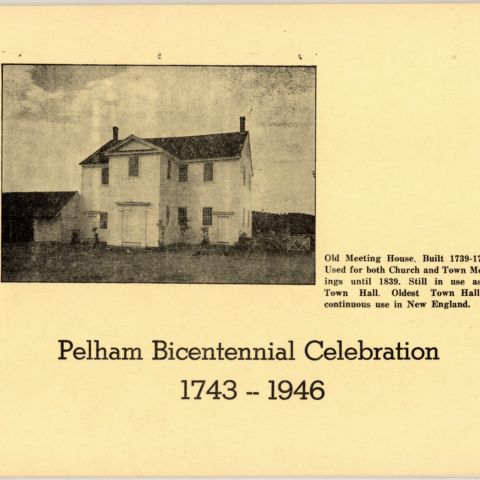

The five meetinghouses built since the founding of the English town of Deerfield, Massachusetts in 1673 were constructed on or near “Meeting House Hill,” a rise of land near the center of town. The original 1690 palisade (stockade), built for the protection of the settlement, enclosed the house lots in the center of town around and including the Common. Eleven houses and the meetinghouse stood within the stockade. In this area today there is a sycamore tree, possibly remaining from the time of the first “turn” (1680-1720). The mile long street that is used today was a dirt road in the English settlement, perhaps following an Indian path that was there before the English came.

In 1728, Harvard student Dudley Woodbridge visited Deerfield and drew some of the things he saw in the town (see Lesson Three). The drawing shows two meetinghouses, an older one and a newer one, perhaps indicating that an old one continued to be used after a new and larger one was built.

A drawing of the 1729 Meeting House, which was taken down in 1824, also exists. Deacon Nathaniel Hitchcock (1812-1900) drew this picture from a childhood memory. The Hitchcock drawing shows that the meetinghouse looks like a church at the time it was taken down, because it has a steeple. This part was added onto the original building. The building has a bell to warn townspeople of fire, and to call them to meeting. There is a clock in the tower, which was important because families seldom had clocks at this time.

A woodcut by John Warner Barber, published in 1839, shows the present day meetinghouse, built in 1824. It is now known as the Brick Church, pictured in the 1995 photograph.

These illustrations give us an idea of the town as it grew over the years. They will be used to orient readers to the meetinghouse, the center of Puritan community life at the first turn of the century.

Deerfield’s English settlers retained a number of customs and beliefs from their Puritan ancestors. The Puritans, who derived their name from the word “pure,” aimed to “purify” the English Anglican church of the time, simplifying services and ridding the church of its Roman Catholic vestiges. Descendents of the Puritans, who eventually called themselves Congregationalists, also didn’t have churches, as we understand the word. Instead of churches, they built meetinghouses that were used for many gatherings, including religious ones. They had simple Lord’s Day/Sabbath (Sunday) meetings, which included many hours of preaching and teaching. They shunned elaborate church rituals. The settlers also believed in the literal truth of the Bible, and put particular stress on the Old Testament. Reading the Bible was considered extremely important, and was the principal reason for teaching children and slaves to read.

There were different reasons a town built a new meetinghouse. Deerfield’s first meetinghouse was burned in King Philip’s War. The second meetinghouse was built in 1682 to replace it, and was quickly replaced itself by a larger one in 1695 because the villagers wanted one “as big as the one” in neighboring Hatfield. In 1729 they built a new, larger meetinghouse because the town was growing. In 1767 this structure was remodeled because the village wanted a steeple like the one in neighboring Northfield. In 1824, the fifth meetinghouse was built solely for worship and its expensive brick construction once again was a statement of the town’s prosperity following the American Revolution.

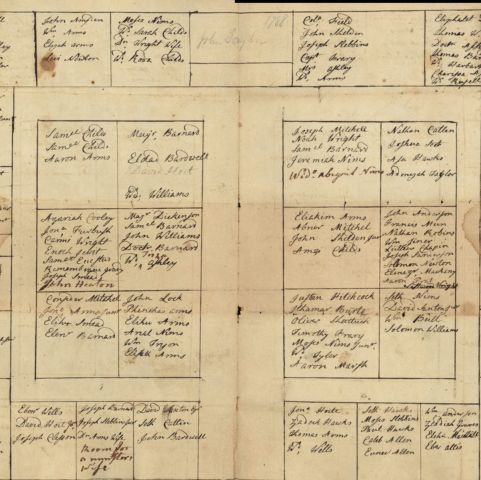

The most important place in the meetinghouse was the pulpit, which was high and prominent. There were two floors, but the upper one was not a full floor. It formed a balcony (called a gallery) so that people sitting there could see and hear what was going on. There was no organ in Deerfield until the 1850’s, but other New England towns had them. Many conservative Congregationalists believed that instrumental music was not appropriate for worship. At first, long benches were used, but gradually enclosed-boxed pews were built and assigned to specific townspeople. There was a committee of men to assign pews. Pew maps, showing the assignments in certain years, survive, and through these seating plans, the social “rank” of individuals and families can be understood. Nearly everyone in the village came to Sunday meeting. The most important people in town had the best pews close to the pulpit. The most important people included those who were prosperous and those who were honored by virtue of age, service to the community, or education. Native Americans and African-Americans sat in back or in the gallery. The meetinghouse was unheated. The pew walls were high and each pew had a door to keep the draft off the worshipers. If a foot stove or heated stone was in use, the pew walls helped contain the heat.

The worshipers spent most of their Sundays at the meetinghouse. The Bible was read. Psalms, songs praising God in the form of poetry, were sung to simple tunes by the entire congregation either without accompaniment, or with a stringed instrument such as a bass viol. The sermon, often used more than once, was sometimes read by the minister and sometimes delivered from memory. Occasionally, ministers’ sermons were published, to be read at home by parishioners. To make sure that everyone stayed awake during the long services, a “tithing man” walked among the congregation carrying a long pole to prod people who were falling asleep. There was time between morning and afternoon services for a meal. Church members went home if they lived close enough, or (as the town grew) to a tavern for the noonday meal.