Feb 29, 1704

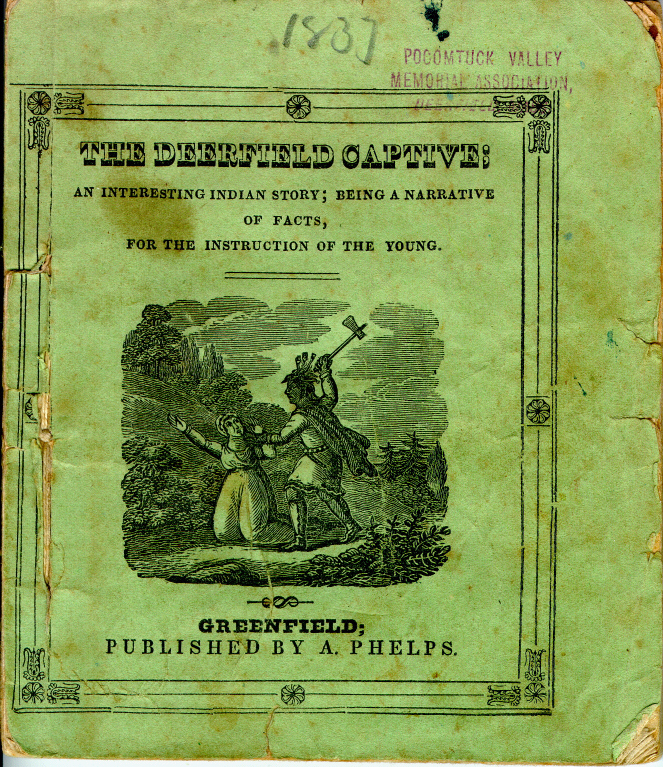

On February 29, 1704, the sun rose on a chaotic scene in the English town of Deerfield. Bodies lay in the street as plundered houses burned. Led by a French lieutenant, a force of 47 French Canadians and 200 Abenaki, Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk(, and Wendat (Huron) attackers had launched a devastating, successful attack on England’s northwestern-most North American settlement.

The Deerfield raid was part of Queen Anne’s War (1703-1715), also called the War of Spanish Succession. Determined to weaken England’s presence in North America, France sent soldiers from New France (Canada) to attack English settlements and outposts. Indigenous nations fought alongside the French, determined to keep their homelands safe from English expansion and maintain their traditional sovereignty.

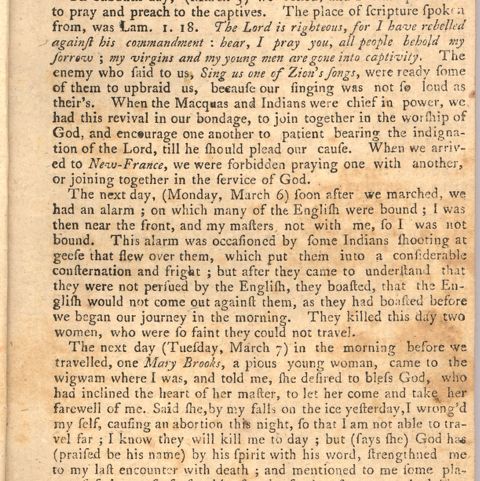

Of approximately 300 men, women, and children in Deerfield that day in 1704, over half were killed (48) or captured (111.) The attackers herded their captives across the icy Pocumpetook (Deerfield River ) and readied them for the 300-mile winter march through Abenaki territory to New France. Many captives were unable to keep up and perished along the way.

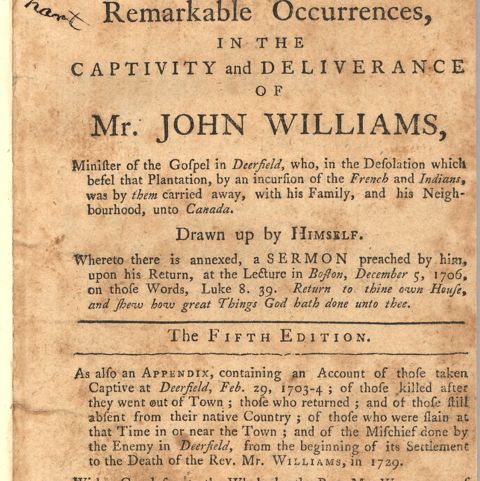

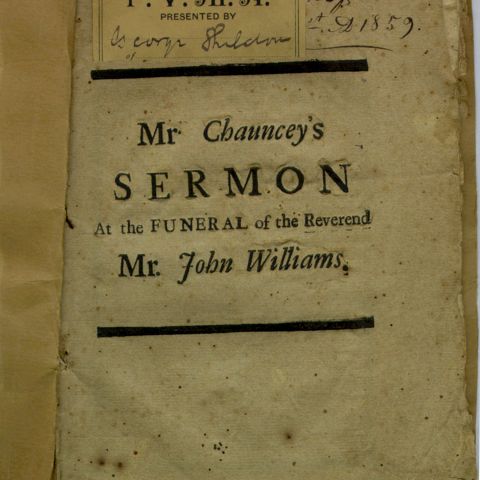

Among those captured were the Reverend John Williams, his wife (killed on the journey to Canada), and several of their children. The minister survived the march to Canada, was ransomed, and made his way back to New England. Upon his return, Williams wrote an account of his captivity, The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion. The book was a best seller and heightened awareness of the raid on Deerfield for generations to come.

Not all the surviving captives returned. Some chose to remain with their adoptive Indigenous or French families in Canada. Among them was the minister’s daughter, Eunice. A Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) family adopted the seven-year-old girl and refused to part with her. Ransom negotiations dragged on for years but Eunice ultimately decided not to return. As Kanenstenhawi, she embraced her new life and community. She converted to Catholicism, married a man from her village of Kahnawake, near Montreal, and lived the remainder of her long life there.

The adoption of Deerfield residents like Eunice into Indigenous communities fostered ongoing relationships between Deerfield and several Native American nations. Over the years, former captives and their families, including descendants of Eunice Williams/Kanenstahawi, visited Deerfield. These visits, as well as formal and informal gatherings and events, have refreshed and celebrated their unique connections to the present day.