“In the beginning all the world was America.” John Milton (1608-1674)

The English settlers who came to New England were, in general, of an ordered, religious ilk and they pursued settlement in keeping with their interpretation of the Bible. It taught them that the Garden of Eden was a disciplined and, therefore, good environment and the wilderness into which Adam and Eve were cast out was chaotic and thus, bad. Their views toward Indigenous peoples were similar – that the harshness of the wilderness accounted for their “savage” state. They lived an untamed existence in an untamed world and the mission of the new settlers was to civilize the people and the land to Western European specifications. The English believed wholeheartedly in the concept of “vacuum domicilium.” For, “it is a principle in nature that in a vacant soyle, hee that taketh possession of it and bestoweth culture and husbandry upon it has an inviolable right to the land.” The challenge of the yeoman farmer was to convert the land from a (useless) wilderness to a (useful) garden in the name of God.

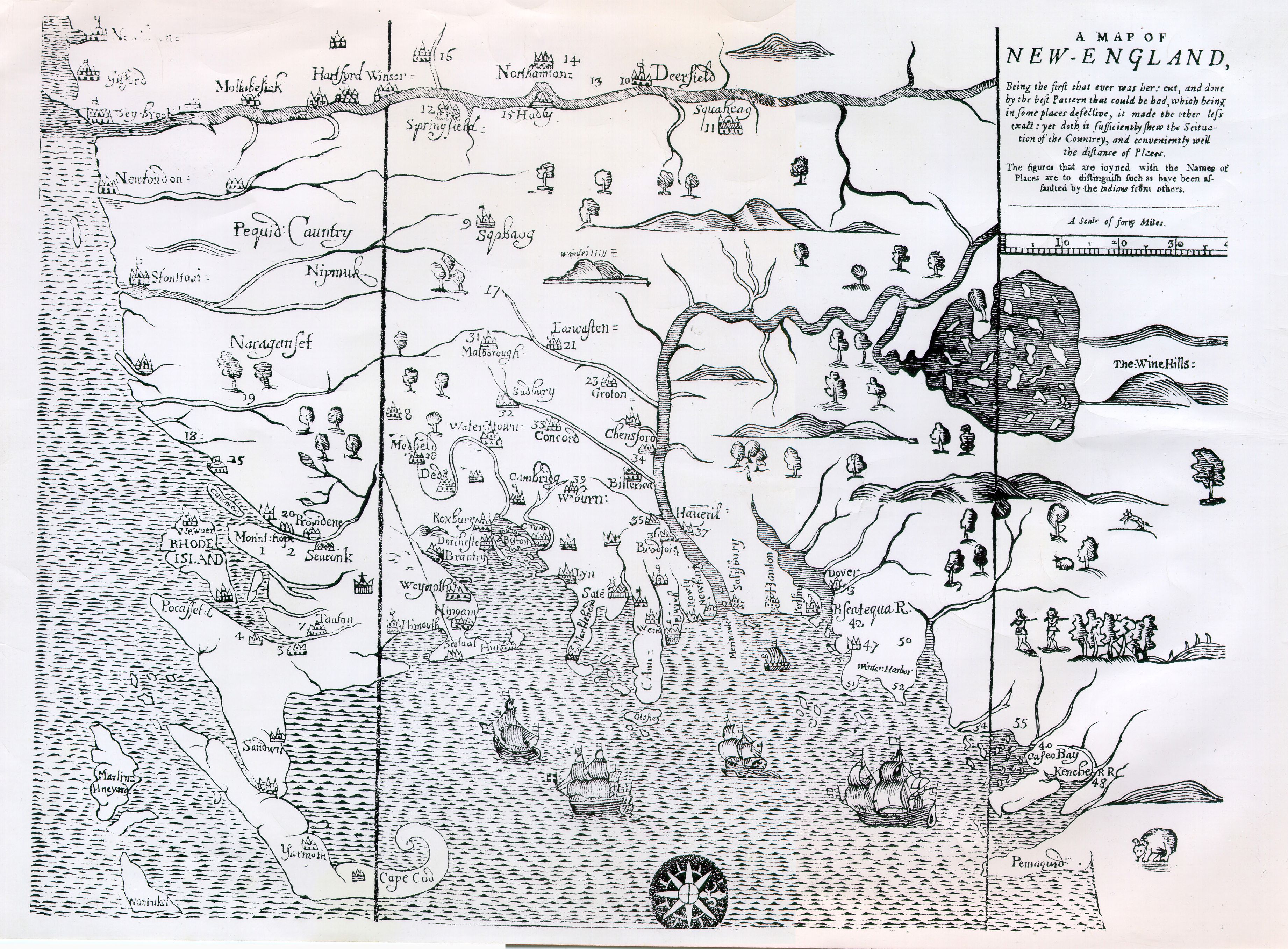

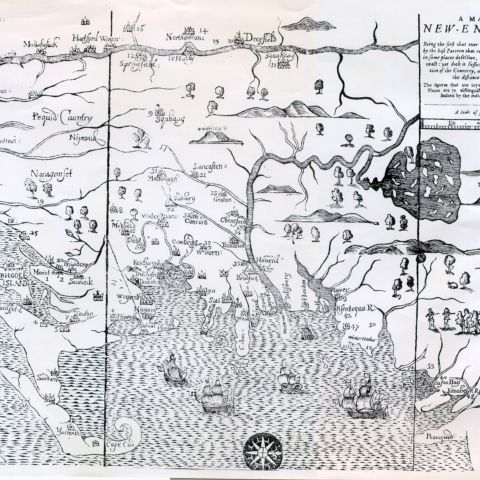

The first wave of English immigrants did not expect to realize the full benefits of taming the wilderness. Each push westward – from the seat of the Massachusetts Bay Colony at Boston to Watertown or to Medfield, to Dedham and hence to Deerfield – resulted in both losses and gains. Their standard of living was initially diminished, but that loss was balanced by being able to own the land. There was the promise of prosperity and it would come to the descendants of those who stayed.

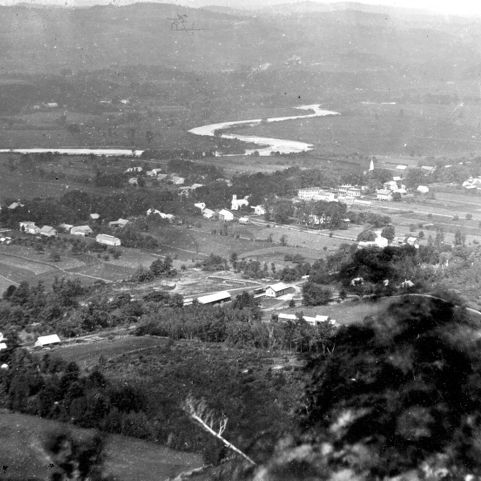

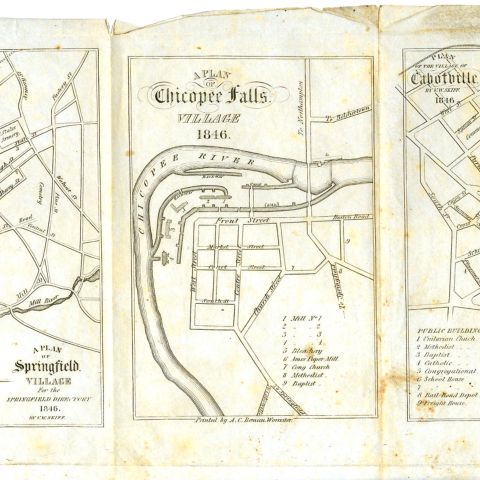

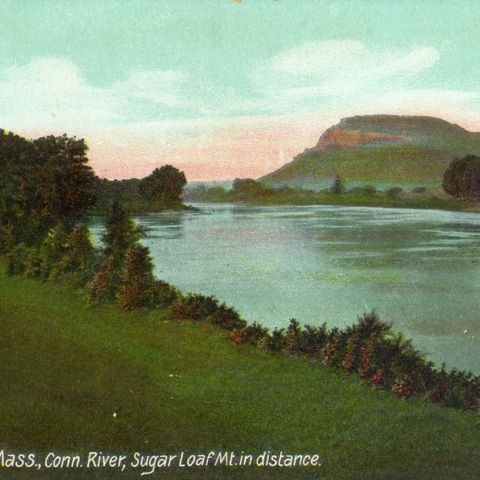

The settlements in the Connecticut River Valley, as elsewhere in New England, were settled in an orderly way, as towns, and not as individual homesteads. The river towns were often laid out on land previously cleared by Indigenous peoples. Forests had been burned, usually annually in the autumn, to keep them open for ease of travel and for better observing approaching enemies. The English utilized the first terrace above the river for tillage, taking advantage of the refertilization supplied by the spring floods, and assigned the second river terrace, above the flood plain, for the village street and homelots. Each family was assigned a long lot, averaging three to six acres in size, for a house, kitchen garden, orchard, and outbuildings. Fields for grains, corn, and hay were located beyond homelots and although in Deerfield they were all within one long fence, strips of land within were individually owned. Mills were built along rushing streams and the woodlots, also separate from the homelots, provided building material and fuel.

Springfield, established in 1636, was the earliest Massachusetts town along the Connecticut River, and was founded by William Pynchon, a merchant and trader of note. The Pynchon family held a powerful influence over the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts. During the 1650s and 1660s settlers established, with William’s son John’s assistance and encouragement, a series of towns along the river north of Springfield.

These tightly clustered settlements were focused on the meetinghouse and maintained a high degree of internal social order and self-maintenance. Attendance at religious worship was obligatory. Although the fields were individually owned, farmers shared their labor and equipment. In Deerfield all landowners were required to maintain a portion of the common field fence, which, by the early 18th century, was nearly 14 miles long.

Deerfield was one of the new English settlements along the valley of the Connecticut River in the 1660s. The General Court granted 8,000 acres to the proprietors of Dedham, Massachusetts, because a section of their town had been designated as a “praying town”- an English-style Christian settlement for the Indigenous peoples in their area. Those English living where the praying town was to be were forced to move and the Dedham proprietors planned to offer them land in Deerfield. However, most of the displaced residents chose not to settle in Deerfield because it was still considered a dangerous wilderness. They sold their rights to their property to others already living in Western Massachusetts who were more accustomed to living in unsettled areas.

The land the Dedham proprietors chose to become Deerfield was the homeland of the Pocumtuck people. Deeds (at least five) were drawn up by the English to purchase the land and although the Pocumtuck people did not understand the concept of exclusive ownership, the put their marks to the deeds thinking they were agreeing to share their homeland. However, to the English, the deeds served to legally legitimize their full rights to it.

The next step in the orderly process was to hire a surveyor to lay out the homelots and the fields. The plan of 1671 by Dedham surveyor Joshua Fisher served to permanently transform the land at Pocumtuck from the source of livelihood for a mixed agricultural, hunting and gathering people without permanent dwellings or fixed claims to the land, to an ordered and owned landscape of English agriculture and husbandry, strengthening the already accepted premise that by enclosure, agriculture, and the establishment of permanent dwellings that a long-term claim to the land could be established. When Joshua Fisher presented his report on May 16, 1671, he had defined forty-three houselots laid out on both sides of a six-rod-wide common street running north to south on a mile long elevated “banke or ridge of land.”

The Proprietors first determined the location of each Proprietor’s houselot based on a random drawing and then worked out each lot’s size based on the number of cow commons each Proprietor held in Dedham. The eventual placement of the houses, facing each other on the mile-long street, suggested both a Puritan watchfulness and a healthy respect for the dangers of the wilderness behind them.

Although the layout of the town and the system of governance that was adopted followed common practices of other English settlers in other English towns, there were some departures. Only a few of the Dedham men came to Deerfield; most of the original Proprietors speculated with the lands and sold to others from the east or from towns south in the Connecticut River Valley. As a result two very different groups of people established residence: 1) the Dedham Proprietors, a formal, careful, legalistic body who ordered the Town Plan; 2) the Others, a rougher, poorer group of risk-takers.

By 1673 the new town of “Paucomptucke” – soon to be Deerfield – was granted, by the General Court, “the liberty of a towneship.” This meant the actual settlers would manage the affairs of the town, since most of the men with strong Dedham connections had sold or had failed to claim their rights. In addition, the General Court increased Pocumtuck’s land holdings from 8,000 acres to a tract “seven miles square,” provided an “able and orthodox minister” be settled within three years. In 1675 there were about two hundred residents, the adults ranging in age from eighteen to sixty-six. Early Deerfield was as poor as any village in Massachusetts. The struggle to survive in the hostile environment took time and energy away from the task of making a living and, in its position “at the very tip of a thin knife blade of settlement” up the Connecticut Valley, the town was isolated from resources and markets for trade. The very fact that the settlers had placed themselves at the narrow north end of their seven-mile-long grant, far from the neighboring town of Hatfield, implies that they knew where the good farm land lay and were willing to accept isolation in the bargain.

In its governance, economics, religion, and social order, Deerfield was inwardly directed, closed, interdependent, and communal. As for “rugged individualism,” a trait often associated with people on the frontier, in Deerfield the frontier drove people together and actually inhibited individualism. The people may have had a vision of what their town could be but they were driven by what it had to be in a rough, rude, violent, and unpredictable world. In a sense, they maintained not one community but a web of communities: first, a ring of governance that was small, tight, and rarely extended beyond Deerfield itself; second, a ring of economics that was slightly wider and included the nearby towns with barter and trade; third, a ring of kinship and religion that stretched further down the Valley; and fourth, a ring of military involvement which included the larger world of Springfield, Hartford, Boston, and even Europe and England. Deerfield was alone, but it was not hermetically sealed; it was a part of a larger world.

Deerfield sat on the edge of English settlement for forty years and while it did the frontier dominated its life. The frontier was fluid and was capable of expanding and contracting, more porous than hedge-like, with trade and interaction between Indian and Indian, English and Indian, and English and English throughout the 17th century, but the risk of disappearing was a risk that was felt every day. When the frontier line of settlement moved on after about 1715, with the establishment of the line of forts across the northern boundaries of present-day Massachusetts, the re-establishment of Northfield, and the eventual settlement of the hill towns to the west, Deerfield changed. The people gained a security which, in turn, bestowed continuity. After half a century the town kept a generation of settlers intact and began to witness steady growth from within. Protected by water and hills, tamed to their standards, and surrounded by rich farmland, neatly cultivated, with their fruit trees arranged in neat rows, the people in the town of Deerfield could see, from every direction, order wrought from chaos.