Marion Kuklewicz (1932-2017) of Turners Falls, MA; interview by David Nixon 3-1-1994; (Tape 7 of 16 ); TAPE 1 OF 2 –

Edited by Pam Hodgkins 5/28/2025; Jeanne Sojka 8/4/2025

David Nixon: Good morning. It is the first day of March, 1994. My name is David Nixon.

I’ll be conducting an interview with Marion Kuklewicz, who lives at 22 Worcester Avenue in Turners Falls, Massachusetts.

Marion: Good morning, David.

David: Good morning.

Marion: I’m glad you could come out and visit with me this morning, and if I may reminisce a little about some things that are real important to me in my life, and perhaps something has brought me to a place in time where I’m much more aware of the rich heritage that I share. And I guess I should start at the beginning, but I’m going to tell you something that happened to me six years ago. Well, it will be six years in September of 94.

I had an elder sister who had been very ill for two years with cancer, and she passed away in September six years ago.

David: What was her name?

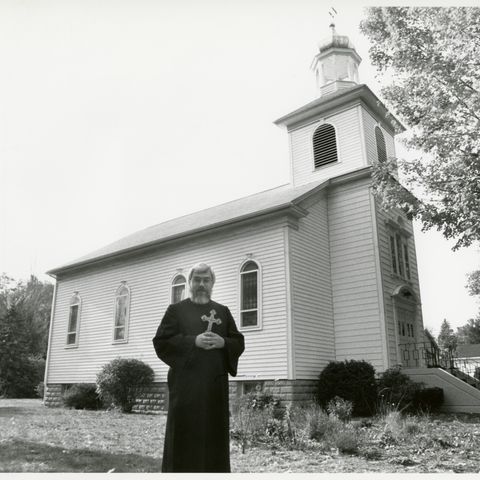

Marion: Her name was Rose Dacyczyn [1922-1988], and that’s not D-E-C, it’s D-A-C-Y-C-Z-Y-N, and that’s an old Ukrainian name. Now, my sister Rose had married a boy [Joseph] who was Ukrainian, and so she had always stayed in our family parish in South Deerfield, Holy Ghost Ukrainian Catholic Church.

And it was at her funeral that something very strange and wonderful happened to me, and as I asked people about it afterwards, it seemed as if I was the one who was most affected by this. We were sitting in the church waiting for the sermon to start, and it was drizzling and raining out, which was kind of fitting, you know, it was really a sad day for all of us, and so it was kind of fitting that it was overcast and gray. And the church was a real special place for my sister.

She had always belonged here from the time of her birth until the time of her death, and was a trustee and a treasurer of the church and so forth. So this was very special, going to be a very special day. The church was very crowded.

It’s a very small, little wooden church, and it was packed. People were standing. And we got in there, and the priest started the celebration of the liturgy, and then he started to eulogize Rose as it came that particular time in the service.

And as he did, he said, “From this day forward, she will be known as Saint Rose.” And when he said those words, the sun came out, and through the stained glass window on the right-hand side of the church, it seemed like a beam of sun came through, and it rested right on my left shoulder. And at that time, I had such a feeling that went through me, it was almost, not fear, but it really shook me, and I had goosebumps, and I kind of just, well, it was like, it was like awe, is all I can say.

It was just awesome. And I turned to my other sister [Katherine Moszulewski] who was sitting next to me, and I didn’t notice that she was experiencing anything, but I didn’t say a word. And after the funeral service was all over, we went to the cemetery, and then we went back to my sister’s house.

I had asked her if she felt anything, and she said, “No, not particularly.” She said, “Except we were all very sad.” And I said, “Yeah, we were.”

But I said, “Did you feel anything else?” And she said, “No.” So I thought, Well, I better not say anything, because people are going to really think I’m off the wall. I mean, I know I’m upset, and mourning for my sister and all, but they’re going to really think I’m off the wall if I tell them what happened.

But I kept thinking about it and thinking about it. And a little later in the day, as we were having a meal together, sharing, all of us sharing in our soil and relatives and friends from out of town who were there, I was busy serving them and all. And then Father Basil [Juli] came along to pay his last respects and to join in the meal with us.

And I sort of singled him out and went over and sat with him and had a cup of coffee with him and began talking to him. And I said, “That was a very moving service.” I said, “In fact, something happened, and I’m not quite sure, but something happened to me then.”

And I said, “But I don’t know what it is, and I have to think about it.” And he said, “Well, Marion, when you want to talk about it further, come and see me.” And I said, “Oh, yeah, I will.”

Well, I never intended to really do much about it. I thought, You know, this is really, you know, it’s, you’re sad, you’re upset. You’re very attached to your sister, so it’ll go away.

This feeling will go away, and you’ll be fine. Well, it didn’t go away. And I would go to work.

And sometimes when I would get out of work, I would get in my car and intend to come home [Turners Falls]. And the next thing I knew, I would find myself in South Deerfield. And that’s not even the direction I should have been driving in.

And I’d go into the church, and I’d sit there, and I would just pray and sit there and think. And a lot of times, I would cry. And I thought, Well, that’s okay.

You’re just dealing with your emotions. A lot had happened during this year. In the start of this year, I had lost my mother’s sister [Annie Biscoe, 1907-1994?], who was our only real aunt that we had.

We had lost her on New Year’s Day. And my mother was kind of a superstitious person. And she said to me, before she had died many years ago, she said, “You know, Marion, you’ve got to be careful what you do on New Year’s Day, because what you do on New Year’s Day, you’re going to be doing all year long.”

Well, little did I know how much that was going to affect my life. Because on New Year’s Day, six years ago, my mother’s sister passed away. She had been ill, but it was kind of sudden.

Her passing was kind of sudden anyway. 24 days later, I lost my husband. He had been ill for many years with heart problems, but had managed to get through life, and see his children grow up, and see grandchildren, and so forth.

And then in July, I lost another sister very, very unexpectedly. And it was strange, because she had just retired, and she was thinking about how nice it was going to be that she was retired, and now she could help care for her sister who had cancer, and so on and so forth. And just like that, she was just snatched away from us.

And this seemed to affect my sister, Rose. She kept saying, “Why her and not me? I should have gone first. I was the one who was sick.”

It should have been me. It shouldn’t have been her, and that kind of thing. And because of all this sadness, and all the deaths we had in our family that year, it seemed to bring the rest of us much closer together.

And I spent a lot of time with my sister, Rose. And being that that’s how I work as a nursing assistant in the hospital, I was there for her to help her with bathing, doing her hair, doing personal things for her that she probably was too proud to let anybody else do for her. So nonetheless, bring this back to why was I sitting in that church? And I would go and sit in this one certain pew.

The reason I sat in this pew is that’s where I had this feeling. So I thought, you know, it’s going to come out to me. But it didn’t.

So one day, Father Basil noticed that I was there, and he came out, and he said to me, why don’t you come in and have a cup of coffee with me, and we’ll sit down and talk. Well, this went on for several times. Finally, I said to him, I don’t understand, but I have to be here.

It seems like something is drawing me here. I have to be here. And I said, it’s really such a strange feeling that I have.

When I come into the church, I feel at peace. And he said, “I can tell you what it is, but I think you have to discover it for yourself.” So after several times of going down, just sitting in the church by myself, and then actually going and attending a Sunday service, I felt, I need to be here.

This is where I belong. So I talked to Father Basil more. He said, “Yes, Marion, this is coming home.”

And I said, “I think that you’re right. I do feel comfortable. I feel like I’m home.”

I feel like I’m in touch with people that I’ve missed in my life for a long time, meaning my parents, and my grandparents, and brothers and sisters who have passed away, and not that they were church members at that point in time. But nonetheless, I felt comfortable. I felt at home there.

And so I said to him, “You know, I view life like a book, and that when you start out in life, you start writing a book. And though I’ve never actually written things down, I feel like I’m writing chapters to the book. There’s your chapter when you’re a child, and some of the things you do as a child.”

And I have many pleasant memories of childhood. You know, there’s some bad things in there too, but mostly they’re good memories that you have. And then you go on to become a young girl and a teenager.

And then you start experiencing more of life, going out into the world, and working, and getting married, and having a family. And I had completed all those things. I had grown up.

I had worked. I had a family. I had a husband.

I had a family. My children were grown. I now had grandchildren.

I had experienced the loss of my parents, the loss of brothers and sisters, close relatives, and then my husband. And I felt like those chapters of the book were complete. Those chapters were already written.

And from now on, for the rest of my life, I had to write the rest of this book. And so each day that I live is another page, or maybe each week is another chapter of the book. And so that’s sort of the way I viewed life, and I decided that since this had happened to me, maybe it was worth really looking into why this was so important.

And I started remembering things about my childhood, about my parents, about why the church was meaningful to me, and just a whole lot of things. And I found that the reason I felt like I was coming home was that since we don’t have our family home, which was in Sunderland where I grew up, the church was probably the next closest thing that I could identify with family, simply because my mother’s father and my father had helped to actually build the church, carrying materials by horse cart, the lumber and so forth, you know, maybe the mortar and things like that for actually building the structure. So it was very important to me.

And then what I realized after going to the church for a while was that in the seat that I sat in, where the sun came through and rested on me, it also exited through a window. And the window that exited through was the window that’s dedicated to my grandparents, my grandmother and grandfather Bishko [Biscoe], on my mother’s side of the family.

David: What’s that name again? Bishko[Biscoe], How do you spell that?

Marion: They spelled it, because of the way it was spelled at Ellis Island, they spelled it B-I-S-C-O-E. But it may have been and has been spelled in the past in other members of the family as B-I-S-C-O-E. When you look at the window in the church, you don’t recognize it as spelled that way, because it’s spelled in Ukrainian.

And that’s, I believe, a Cyrillic alphabet. So it looks different. It almost looks B-I-M-K-O, I think, is sort of how it looks when you see it written.

And my grandmother’s name was Anna. And on the church window, it looks like A-H-H-A. But that translated as Anna.

And my grandfather’s name was Alexander, which again is a good Ukrainian name that’s still used a great deal today. So that sort of brought it all together. And that’s sort of when I started really looking back and looking into the past and wondering if there was a reason for me to be back there.

And I now feel that the reason I was back there is that suddenly, I became much more aware of the heritage that I shared. A heritage that was sort of, that we’re sort of losing contact with here in the valley. Many people for many, many different reasons have sort of lost touch with who they really are.

And many people who are of Ukrainian descent or some of the other close-knit Eastern countries, the, some of the Ukrainians, the Hungarians, Czechoslovakians, Lithuanian, gee, I can’t think of some of the other countries, but they sort of went, they wanted to belong to a church. We didn’t have a church at first when we came. So many of them passed themselves off as Poles.

David: Why’s that?

Marion: It was easier to be a Pole in this valley than it was to be some of the other denominations that I mentioned. There was a lot of, there was a lot of, people kind of looked down their nose at you. They didn’t really understand where you came from.

I can remember even as far back as when I was a child in grammar school, even though I was born in this country, there were some people in the town that I grew up in and some of the kids that I went to school with that looked at us like we were green horns, you know, fresh off the boat. And actually all of us were born here because my father came to this country with a very young child. And my mother was actually born here.

Her parents were born in either Ukraine or Austria. And again, depending on where the border was at that moment in time as to where they actually came from. But my own father was born in Brody which is in Ukraine.

It’s not too far from Kiev here. And we used to get picked on. And so it was easier to just say you were Polish because they seemed to be more respected than some of these other ethnic groups.

And so for that reason, many, many people just sort of passed themselves off as Polish. You went to a Polish church or a Catholic church and that was it. But our group, our little group of people who are family fathers still have many relatives who participate and go to the little world church in South Deerfield.

We seem to be aware of who we were and who we wanted everybody to know that we were. And the reason that I had been away from the church was when I married, one of the laws in our church was that when you married, you followed your husband. Most, like a lot of churches you marry in the wife’s church and that’s sort of where you go.

It’s usually an understanding if you live near. But in our church law, you followed your husband. And I used to jokingly say, but nobody told me I had to walk two steps behind.

And we sort of joked about that all the time. But that was how it was. And so what happened is like in my family, we were a big family.

There were five girls and there were five boys. The boys sort of were scattered to the far winds, many different states where there weren’t communities that they could join the church, similar to ours. And then three of us married men that were of Polish extraction.

So naturally we followed them. My sister Rose, who was the one who had always stayed in the church, married a Ukrainian boy. So she stayed right there.

And then my sister, my youngest sister [Irene Olanyk Cheney, 1934-2015], married someone who was of Irish descent. So she again followed him and went to sort of a non-denominational Catholic church. So here I was for 35, yeah, about 35 years while I was married to my husband and having our family, we were practicing as Roman Catholics.

And it was okay.

David: Your husband was Polish?

Marion: My husband was Polish and we practiced as Roman Catholics.

David: And his name was?

Marion: Henry George Kuklewicz or Kuklewicz, whichever way you choose to pronounce it. We always said Kuklewicz because it was easier for the kids to sound it out and spell it that way. But in Polish, it’s Kuklewicz.

So anyways, his family had belonged to a Polish church [Our Lady of Czestochowa]. And then there was some problems. And so they decided to join a Catholic church that was non-denominational, [St. Mary’s Church, now Our Lady of Peace].

And that’s where my children grew up. That’s where they were educated. So what happened to me was that then my children grew up to be Roman Catholics.

And I had followed that faith. But after the death of my husband and this thing that happened to me when I was in church, I knew that I had to go back. And it wasn’t easy.

Some of my children weren’t sure that I should go back. And I just said to them, “Well, I feel I must. And there has to be a reason for this. I don’t know what it is at the moment, but I know that there’s got to be a reason for it.” And we kind of joked about the reasons and all. But I really think the reason is that that particular moment in time made me realize that I needed to let people know who I was, why I believed so strongly in my faith, and that it’s really important to me.

And that it’s important for my children to know that there was another side to this family other than the side that they, you know, followed as children. And I think they’re beginning to realize more that though my husband and I were, we were not really that far apart as far as religion was concerned. But that we had taken the best of the best and combined it so that we were able to carry out a lot of the traditions that were similar to both of us.

We were not, we were not able to do everything. But the main celebrations at Christmas time and at Easter time, we just sort of combined the best of both and pulled it together so that they have some feel for the traditions. And it was important.

Christmas Eve is our big important time. And it was always a family time. And we had always stressed that this was a time we all had to be together.

But as families go and grow and marry and, you know, different things happen, it isn’t always possible for them to always be home. But that was the goal. That was the goal we had established as a family, that we would all be together.

If not any other time of the year, that would be one time when we should all be together. And it wasn’t just because, you know, it wasn’t because of Santa Claus. And it wasn’t because of the presents.

It was because of our deep religious conviction that that was an important time to be together. Easter was another very important time for us. So the birth and resurrection were always, you know, foremost in our mind.

And we needed to be together and celebrate and feast and all the other things that went with it. I mean, the Santa Claus, the presents and all that, that was not important. The important thing is the religious aspect in that sort of way.

We hoped our family would see it as they grew up. But you know, America has changed a great deal and values for everybody have changed. But I think as my children are growing older, that they’re beginning to see where I’m coming from, what I’m all about, that they’re beginning to rediscover.

David: I was going to ask you, if you’re writing a book, your life is a book, and this is another chapter. What’s the story? What’s the moral of this chapter that you’re writing now?

Marion: That I’m writing now? I guess I’d have to call it awareness. An awareness, like I said, of who I am, where I come from, and why I have this feeling that this is where I belong, this is where I need to be.

Spiritually, I think reflects a lot of how I think my value system that I grew up with. This is all important.

David: Can you stop for a minute?

Marion: Sure.

David: Why don’t we start? Okay. Can you tell me about your father?

Marion: Oh yeah, that’s kind of an interesting story, I think. My father came to America when he was a very, very young boy.

It seemed that he was one, he was the eldest of five children, born to his parents in Vlody, in Ukraine.

David: How do you spell Vrody?

Marion: V-R-O-D-Y. David: And what was his name?

Marion: My father’s name was John Olanyk.

David: No, it wasn’t John in Ukraine, was it?

Marion: No, it wasn’t, but someone asked me to pronounce it in Ukrainian, because I have a hard time. But John is what it was in the United States. Probably something like Januk.

Januk is probably more Polish than Ukrainian, but it’s probably something similar to that. In Olanyk, we questioned whether it was actually spelled O-L-A-N-Y-K in the Ukraine, or whether it was more probably spelled W-O-L-A-N-Y-K.

David: How old was he when he came, left Ukraine?

Marion: Well, my father was probably somewhere around 12 or 13 years old when he left Ukraine.

And he left under rather terrible circumstances. He was, as I said, the oldest in a family of five. His mother and father lived in a small farming community, which most of the people that have come to this area are from small farming communities.

They were actually peasant farmers, but because they owned land, were perhaps a little bit more prosperous than some of the people who worked, you know, out for other people. And his father, at that point in time, was in the Ukrainian Cavalry and was killed. He was transferred by a force.

David: And so… Do you know what your father’s father’s name was?

Marion: I believe it was Michael. No, it wasn’t. Excuse me.

It was Thomas. It was Thomas. His name was Thomas.

And his mother’s name was Mary. And Mary. Thomas and Mary.

David: And what time are we talking about? Was this in the 19th century?

Marion: It was in the 19th century. My father was born in the 18th century. In fact, if he were alive today, I think he’d be 102 years old.

102. 102, yeah. And he actually had quite a disagreement with his mother and a gentleman who wanted to marry her after his father was killed.

And his feeling was that this man wanted to marry his mother to obtain the lands that they owned. And this was something that was very much against his father’s wishes. Since he couldn’t convince her not to do this, he had a terrible argument and a fight with the proposed stepfather and decided that he would run away from home and come to America, which I really don’t advise children to do in this day and age.

But he was a very daring, determined man. And so this is what he set out to do. And I don’t really know the story of how he got from Vrody to the sea in order to get on a boat to come to America.

But some way or another, he made his way to the shipyard and got on a boat.

David: Do you know which port he left Europe from?

Marion: No, I don’t.

David: Do you know the name of the ship?

Marion: No, I don’t know that either.

I don’t remember that. Like I said, I was only a child. I was only 12 years old when my father passed away.

And so there’s a lot that I don’t know. There are a lot of missing links. And unfortunately, my older brothers and sisters have all passed away, so I’m not able to gain much knowledge from them.

I do have an older brother that I need to talk to and see if he can give me any clue as to the ship. The other thing is he came without a passport. He didn’t have a passport.

He came with a stowaway. He was a stowaway. He was a stowaway.

How he got on the ship and was able to conceal himself again is not something he revealed. I think he probably didn’t want to talk about it very much when we were youngsters. Probably didn’t want to put any grand ideas in our heads.

And also, I’m sure he realized that was a very wrong thing to do. But nonetheless, he was determined he was going to come to the United States. And I don’t know whether he heard those stories about the streets being paved with gold.

But I know when he came here, [1908?], he found that they weren’t paved with gold. And that in order to make his way, the thing that he was going to have to do was to work.

David: Now, before we get to where he got off the boat, you said that he was a stowaway on the boat.

David: He got caught, didn’t he?

Marion: Yes, he did. And I’m sure that he had to work his passage by working on the ship. And like I said, the ship that he came over on, he always described it as cattle boat.

And he said the conditions were really horrible. They didn’t have berths or bunks or whatever you have on ships now. They came under very primitive conditions.

He always talked about the straw on the floor that they slept on. There were not proper toilet facilities on the boat. So I would assume that probably was his job, was helping to keep that part of the ship clean.

And this would probably be a suitable penance as it would be for someone who was trying to take advantage of the system and, you know, get a free ride, so to speak. I think it turned out that he probably paid very dearly by working in cleaning up, you know, on the ship and getting through it. But nonetheless, a problem arose when he got to New York and they were going to get off the ship and go on to Ellis Island.

He didn’t have a passport. He was without parents and had a very difficult time.

David: How was he going to do that?

Marion: So he posed as the son to a family that was going off the ship in New York and was able to get off posing with their son.

So one of the things that I need to do in my lifetime is I need to go to Ellis Island and see if he’s really listed there.

David: You know, we’ve got this trip coming.

Marion: Yeah, I know.

I know. And that’s, I’m planning on doing that and see if his name is actually logged there or if it isn’t. I don’t know.

That’s something we haven’t really investigated, but it’s something I certainly intend to do. But in any case, he got off the ship and then I believe what happened is there was a family in our town who were quite prosperous. They were a family farm, a farm family, but very prosperous people who lived in Sunderland.

And they would go into New York and pick up the boys and young men who came off the ships and bring them out to work on the farm for them. And since that was what my father was well versed in doing, that was not a problem for him. He took to that very quickly and worked probably mainly because he was so young.

They probably had him work a full boarding room, give him a place to sleep and three meals a day and he worked. And he got a little older, then he started getting his salary. And he worked on a farm right along the Connecticut River in Sunderland.

The land that borders the Connecticut River is the farm that he worked on. And then some land, I think in the northern part of Sunderland they also farmed. But this farmer was growing produce, potatoes, carrots, onions.

David: And what was the farmer’s name?

Marion: The farmer’s name was Charles Clark. And that’s a very noted family in Sunderland, very prestigious family. And there are family members who still live on the main street in Sunderland, one of the big old houses there on the main street.

My father always loved that land because it reminded him very much of what he was used to at home, very fertile land and all. Back in Ukraine, they grew, of course, their gardens and vegetables and so forth with food. But the territory that he grew up in was very noted for their wheat production.

Wheats and grains were very, very much the thing to grow there. And though they were, you know, they were modest farmers by some of the farmers that you see here, they were able to support themselves, having enough food to keep them from one season to the next growing season. They were able to harvest their grain, feed their animals, turn some of it into flour for bread, others that were used for, you know, general cooking, and were able to support themselves and live a fairly comfortable life.

So farming was what he knew, it was one of the things he loved. However, he decided at one point, he was like, we want to do more than farming. So he had gone to [unintelligible] and they took courses to become a barber.

And he started doing that. He thought that might be a good trade to know. And most of the people who came over looked for something to do besides, they didn’t just have one occupation, sometimes they would have two, so they would have something to fall back on.

And therefore avoid those lean times in life, and wonder where the next meal is coming from. And he started becoming a barber. But even though my father was a farmer, he was a very meticulous man.

And back in those days, when you would give haircuts and trim beards, it was not uncommon to find head lice and so forth. Because a lot of people came, again, in such very primitive conditions and so forth. And he didn’t like that at all.

So he gave up barbering. He thought that was too dirty an occupation. He didn’t like that.

So he went back to being a farmer. And somewhere along the line, because of his work in Sunderland, he became acquainted with my [maternal] grandparents. I would assume, and again, this part of the story is a bit vague, I would assume that he probably met them through my grandmother’s relatives in the Sunderland area.

Because they were of Ukrainian, they were of Ukrainian, Czech, Hungarian, Lithuanian, they were of those groups of people. And they would get together maybe on Sundays and holidays and talk about home and maybe have some partying, picnic type of partying and so forth. And became acquainted with my grandparents.

And then they started talking about establishing a church in the community. And I’m sure this is where the connection came. And at the time, my mother was growing up to be quite a lovely young lady.

David: What was your mother’s name?

Marion: My mother’s name was Julia Lena Biscoe. And her parents’ names were Alexander and Anna Biscoe. And at this point in time, though my mother was born right in a house that was right on the line between Sunderland and Hadley, they had now bought a little farm.

My grandfather had saved up some money and he bought a little farm which was on the Amherst Road in Sunderland. And unfortunately, that bit of farming area is no longer farming. It’s now apartments.

David: That’s where the Cliffside Apartments?

Marion: Cliffside Apartments, Squire Village, that whole section there, that property all belonged to my father and my grandfather at one point in time.

David: Now what did, before your father met your mother, what did he do during the wintertime, during the summer and the spring and fall he worked in farming? What did he do during the wintertime?

Marion: In the wintertime, he probably spent a great deal of time working in the woods as a wood chopper, logging. There were many houses and homes that needed to be built in the area.

So he probably spent a great deal of time doing that sort of thing. The one thing that was my father’s great love was horses. And I think that came about naturally because of his father’s connection with horses.

But my father really loved horses. They were probably better friends to him at some time than people were. He really, really loved horses.

And so I’m sure he probably worked in the woods with a team of horses, drawing out logs to take to the sawmills to cut the lumber and so forth. Also, he would, I don’t know what the word would have been back then, but I’m sure when the means of travel was more by horse and carriage than by cars. I’m sure in the wintertime he also offered his services as a team driver to take people to and from, maybe get supplies from the city, you know, into the villages and things like that. I can remember him talking often about going between Sunderland and Montague’s team of horses and sledding and taking produce or whatever back and forth in that way.

Well, anyways, he met my mother, and they were married in wintertime. I guess that tells you all the things they did in the winter. They must have gotten very romantic then.

They probably had more time. But anyways, my mother and father were married in February, February 2nd of, I believe, 1917. They were married in Sunderland, and that was before the church was built.

So I’m not exactly sure when the ceremony took place [February 3, 1914 in South Deerfield], but I can remember my mother talking about the wedding taking place at, the reception taking place at my grandparent’s home, and that the wedding reception lasted three days. And the reason it probably lasted so long was many of my grandfather and my mother’s father’s relatives came from Pennsylvania, so they would have come out for the event and probably had to stay before they could get to the railroad station to get back home. And my mother and father didn’t come here on a wedding trip.

My father had saved some money, and they were able to buy a small farm in Montague, which he and his new bride moved to.

David: Where in Montague was his farm?

Marion: He had a farm in Montague on Ferry Road. It again borders, it goes out towards the river in Montague, and he had the farm there.

And he started growing produce and started a little dairy and so forth in Montague, and that’s where their first group of children were born. And also, I had told you my father was a very determined man, and he was going to make his mark there come, come high, come hell or high water. He was going to be a success.

One of the things he did is he became involved as a salesperson for a fertilizer company. So he was selling fertilizer for this company to the different farmers in the area. There was only one drawback.

My father couldn’t read. He could write his name, but he couldn’t read. So he only could interpret the contracts that he had his farmers sign for what the people, the officials from the fertilizer dealership told him.

He didn’t realize that in fine print there was a clause that said if the farmers were not able to pay for their fertilizer, which everything was brought on credit then, that he would be responsible. So because he didn’t understand, and my mother wasn’t very well versed, my mother only went to third grade. My father probably had very little, had no school in America and had very little schooling probably at home, so he could read in Ukrainian, but he didn’t read English very well.

I guess you’d have to say he was pretty much self-taught. Some educated person. But anyways, the fertilizer company wanted their monies and times were really hard.

The farmers couldn’t pay. My father didn’t have the money to pay, so what was going to happen was they were able to attach the farm and take the farm away from him to pay off the debts that he owed. Well, my mother decided that she had to kind of step in and do what she could to kind of help out.

So what she did was she sold some of her chickens and eggs and maybe a calf or two and ended up amassing a small fortune for them at $200. And that’s what they had to live on for one whole entire winter. They now had seven children, two adults, $200, no home, no place to go.

They came back to Sunderland and stayed in a home that was provided by one of our neighbors and it was nothing more than a shack. It really was a dirt floor shack. We used to use it as a garage at one point maybe in life.

But in any case, they lived in this.

David: Where was this?

Marion: This was in Sunderland and it was off of Route 116 on the right-hand side of the road. The house on that property still stands there.

The house still stands there. It does not belong to my family anymore, although at one point in time my father did own it. But the house still stands there.

It’s a big blue sided house with two huge maple trees in the backyard. It belonged to some friends of mine, my father and my grandparents, and they allowed them to live in this shed. And as I said, I remember that shed very well.

It had wallpaper on the walls, but I believe the floors were dirt. I don’t remember them being solid floors. I still don’t have a very good idea of where it is.

David: Was it in the town?

Marion: It was in the town of Sunderland, right across the street, well almost directly across the street from where Cliffside Apartment is standing now. Okay. Okay, right there in that little valley.

David: So it was on the left side.

Marion: No, well coming from, which way are you coming from?

David: Going from Amherst to the north. Oh, if you’re going from Amherst to the north, it would be on the left-hand side.

Marion: Okay, it would be on the left-hand side. See, I’m always coming the opposite direction because of where I live. I’m always coming the opposite direction.

David: Okay, I know where that house is.

Marion: That big blue house, well there was a shed across the driveway, but it’s a big long shed that we that my parents lived in. I did not live there.

I wasn’t born yet. So they weathered the winter there, probably came in with a wood stove or whatever, and my father probably did whatever odd jobs he could get. Again, anything, he would do anything that was possible to earn two pennies to feed his family.

And like I said, he was a very proud man, but nothing was beneath him except cutting hair and a fun thing that he couldn’t like that. But he would do anything, you know, he would work on a farm, he would work in a lumber mill, he would work cutting wood, anything to earn money to support his family. He did manage somehow to buy another small home in a small piece of property further south on a street that’s now called Silver Lane, but when I grew up in Sunderland, it was called Hungarian Avenue.

And the reason it was called Hungarian Avenue is there were many settlers in that particular section of town who were of the Hungarian nationality. And so some of the so-called elite in the town had dubbed it Hungarian Avenue. But anyways, my folks were able to purchase a house there, a small barn, we had a few cattle.

I’m sure my father had his horses again because he had such a love for horses. And there were seven children when they first moved there. Then I had a brother who was born there.

And again, my father became a little bit more prosperous, working as a farmer, probably worked his own farm, probably worked out for other people as well. He, as they say, he was versed as a young boy in harvesting grain and things like that. So I’m sure he did hay, harvesting grain, working in the woods.

And then eventually, of course, working with a person because he knew about cattle and so forth. And I’m sure whenever there was an opportunity to drive a team of horses, regardless of where it was, he did it. Because that was his great, great love.

I was then born, after they moved to this house in that part of town. I was born there. And as a very young child, we experienced a very sad thing in the wintertime when they were doing their chores in the barn, they used to have to do it by lantern light because we didn’t have electricity at that point in time. Apparently, a cat and dog had gotten into a fight and were chasing each other through the barn, tipped over the lamp. It was in March, it was windy, the barn caught on fire, and everything was lost in the barn.

The barn, there’s flames and sparks from the barn, then ignited the house and they lost the house as well. So there again was this family with now eight children, or nine children. There were nine children, and again, very little money, no place to go.

But my father was able to somehow obtain another house a little further, well actually back, back towards the center of town. He bought another house, which is where, there’s some other apartments there now, I’m not sure exactly what they’re called, or maybe it’s a storage building, but it’s part of Cliffside. There’s another house there, and it was just a little, just sort of across the street, and a little further down from where they had lived in the shack.

They were able to purchase this house, as I remember it. It was a pretty nice house. They had a nice big old family farm kitchen, a dining room, a living room, a bedroom downstairs, and a few good-sized bedrooms upstairs. I will remember that very vividly, and I’ll tell you why later.

But this was the house that we went to, and again had some land with it, which we were able to obtain. Mortgages were probably very easier, very much easier to come by then. Sometimes you didn’t have to go to a bank, sometimes if people needed you, a hard worker, they would just let you pay them a little bit of time, and you could do that.

So he obtained that house and started farming there. At this point in time, he grew onions, potatoes, and he had begun to, along with dairy, he began to start growing tobacco, which was very popular in the Valley, open field tobacco, which is not grown much anymore in this Valley. But that was a crop that you had to take care of very tenderly, and if you had a good year, it could make you a lot of money.

If you had a bad year, then you were lucky if you had money enough to eat and feed your family during the winter. But again, it was a gamble. But with the other things that he did, the produce, the cows, and the milk that he was able to sell, the tobacco, some logging that he was able to do, again, he was able to care for us very nicely.

And my mother, in all this, not only did she have all these children that she had that they did, she had to work just like one of the men on the farm as well. So her day probably started somewhere around four o’clock in the morning. She would get up, go out and help him feed the cattle and so forth, leave us in charge of whomever the oldest one in the house was.

She would go out, help him get chores started, come back in, get a great big farm breakfast ready. And we would come in, and I say we, because as soon as we were over that toddler stage and able to do a chore, we all had to do our chores. And we all had to go out and help in the barn, help with the milking, maybe feeding the calves, or the pigs, or chickens, or whatever.

Whatever we were able to do was our job at that given time. I used to, I always got chicken duty and pig duty, but I was kind of a little lonesome. Those were my two jobs.

I always had to do those before I went to school in the morning. And then we would come in and have breakfast, and then those of us who were old enough to go off to school, they had their breakfast and went back out and did more work. And in the wintertime, it was mainly taking care of the cattle, doing logging, and this type of thing.

And then in the spring and summer, of course, you got real busy with the planting, and the days were very long days, very, very long days. And I guess what I really want to say about this is that my father never stopped wanting land. Land was a very precious commodity to him.

He felt that if he owned land and property, he was wealthy. It didn’t make any difference if you had money in the bank. As long as you could care for your family in a reasonably good manner, they had food and clothes, and one place to sleep, and so forth.

But it was very important for him to keep buying land. He eventually bought my grandfather’s home when my grandfather became elderly. After my grandmother had died, my grandfather became elderly.

His sons were never cut out to be farmers. And my father always used to laugh at me describing my grandfather as a gentleman farmer, where my father was real hard-working, hard-nosed, a perfectionist, really worked hard. He really wanted to amass a fortune was his goal.

He really wanted to be, actually, he really wanted to be a millionaire. You know, and so that was his goal, was to buy more property, grow more crops, become more affluent as time went on. So he then bought my grandfather’s farm, and was able to have more cattle because he had a bigger barn, or he had a barn that you could expand to and have more cattle, more young stock, more horses, you know, more land to cultivate, more pasture land and everything.

So he was becoming much more affluent as he went along. Then there was another piece of land, and it happened to be the piece of land in the house that I spoke of where they lived in the shack. He wanted that piece of property.

He wanted to acquire that piece of property because it was kind of the link between some land that my father had bought from my grandfather. He needed that piece of property to obtain a real right of way to allow our cattle to cross from one side of the street to the other, through a small pasture and down into some bottom land, which was pasture land and also land that we grew our potatoes and onions on. So as those people became a little aged, they decided to settle the farm, and this is when I can clearly remember money.

He bought that farm, and I think it had 32 acres of land, for maybe $2,300, about. That’s when I first became aware of money, and I was probably about, probably eight or nine years old at that point in time. But I do remember that quite clearly, and the house was really in quite a state of disrepair.

As a matter of fact, the first time my mother walked on a porch to go in the house, she fell through the floor with the porch. That’s, you know, it was really in pretty sad shape, but the land was valuable. So the first thing he did was to take off this big wraparound porch because it wasn’t safe, and get rid of that, and began to start fixing the inside of the house so it was more habitable.

And you have to remember, these houses we lived in were, they were real farmhouses. We then had running water. We didn’t have my grandfather’s house.

We had to pump the water, but we had running water. Gradually, we became able to have electricity in the house, but we didn’t have indoor plumbing for the bathroom. We had to go outside to the bathroom.

It was pretty cold. He didn’t go much in the wintertime. It was pretty cold.

And it gradually, this house that he had acquired, which had belonged to a family by the name of Imbowitz [Embowitz], and I believe that they were, I believe that that’s the Lithuanian name. I’m not sure, but I believe it is.

David: What’s the name again? Imbowitz? Could you spell that?

Marion: No, I can’t really. I-M-B-O-V-I-C-H is what a rough guess, but I’m not sure that that’s correct. The man’s name was Karl, and his wife’s name was, um, God, I don’t remember calling her anything but Mrs. Karly [Annie].

Imbowitz was too hard for us to pronounce, so we always called her Mrs. Karly, and I don’t know if I’ll think about it. Gosh, I only remember my family calling her Mrs. Karly. Well, anyways, we bought the house, and then her husband passed away, and she went to be a caretaker for a family a little further, maybe a mile down the road from us.

She went to be a caretaker for their two children, and eventually married the man, and that provided her with a home for the rest of her life. And she married a man whose name was Grossberg, Peter Grossberg. And she had two, she had, um, she had a daughter. Alice was her daughter’s name, I do remember that.

And Alice grew up with another man by the name of, um, um, there’s a space name for him, but I’ll think of it. Bednarski. Bednarski.

The Bednarskis. And, um, they lived in South Deerfield, and they had a church in South Deerfield, the Bednarskis did, and she was, um, Alice, Alice Bednarski was Mrs. Karly’s daughter. And she had been playing with her mother’s.

David: How did your father learn English, or did he learn English?

Marion: He learned English, um, he learned English through speaking with my mother, who spoke English. My mother spoke English, my mother spoke, um, Ukrainian, she also spoke some Polish. And, um, now that I’m more aware of languages, I realize that she kind of spoke a combination.

Because now when I try to speak some words in Ukrainian, I get kind of, um, snickered at a little bit, because I don’t pronounce them correctly. And it’s because I think that they sort of adapted them to be able to communicate with each other. Um, and so he learned to speak English when he came to Sunderland, with the people he worked with.

And then, you know, after marriage with my mother, she spoke fluent English, like, um, uneducated, but fluent in the words that she knew. So he was able to learn, but never really learned to read, um, very much. He could, he could write his name but that was about all.

Um, however, he did become a citizen, so whether they treated them, and it was just by rote that he learned, and then he really learned to read. Um, after my mother, you know, when radio came to be, um, the news that he lived by, you know, world news and so forth, was all getting from the radio. He would sit and listen to the radio at times, things like that.

So, you know, it was getting through that, as opposed to, you know, reading the newspaper like a lot of people do.

David: When did your father become a citizen?

Marion: Um, I don’t know the year, but I would, I would assume probably in the 1930s. Possibly 1932, 33.

David: Did your father ever return to Europe?

Marion: No, no. He, this was the one thing, um, he said when he, when he left his home, he left with the understanding that he was going to live a new life for himself, a new world, as he called it. And he always said he never looked back.

He never looked back. He never saw his mother again from the time that he left. He never saw any of his brothers and sisters.

Um, he did communicate with his mother at one point in time. He wrote a letter to let them know he was alive, and I think she wrote back. And then, after World War II, we lost our, no, not World War II, after World War I, we actually lost all contact with the family there.

I, I have a scrap of an envelope of a letter, and I, I’ve been thinking that maybe the last, um, bit of communication was in the 30s. I’m trying to think if it was 1936 or 37. I would have to get that out and look at it.

But somewhere along in that era was the last we’ve heard of it. So, um, we do know that during the, um, First World War that his brothers were in the service. And whether they were captured or killed or whatever, um, I don’t know.

I have one picture in, well actually my sister had it, and I now have it in my possession, a picture of his brother, um, it was during the wedding ceremony. And it was, obviously, in the wintertime, because they all had their fur coats on, and, you know, he dressed in one, uh, clothing. And, um, that was taken probably in 1936, 37, and it was something that was mailed to him by his family.

But, but I know that he had absolutely no contact with them after, after 1938. They never had any contact with him. I feel certain that we have, um, you know, that we have some relatives there.

Um, I’ve never, we’ve never communicated with them, have no line of contact. The only thing is back in the 40s, um, probably in 19, probably in 1944, 45, um, he did have some contact with a cousin who was living in Michigan. Um, I don’t even remember her name.

It was those, uh, she did come to visit us. Um, Tessie, I think her name might have been, I’m not, I’m not sure. And she and her daughter lived in Michigan, and what her priest in Michigan was, was the housekeeper for a priest in Michigan.

How, um, long she had been in the States, I don’t know. I don’t know when she came, or how she got there, but she was there with the daughter. So I would assume she either came, uh, after her husband was killed, or, or something, but I really don’t know the full story there.

David: Now, you mentioned that your father helped build the, like, the church in South Creek. Mm-hmm.

Marion: Yeah, he did.

Marion: I’m not sure, um, you know, probably not monetarily, but the fact that he was able to, uh, haul things, lumber, and things, uh, probably cement, lumber, those kinds of things, for the actual building of the church. I think of, of the two factions, I think my grandfather and grandmother were probably more, uh, more into, um, probably more involved in the actual coming about of the church building, that they didn’t really have the funds or the means to do that. But I think they were probably more, um, in tune with the fact that the community needed a building, needed a church building, needed a place to worship, um, so were there, you know, as founding, the founding fathers of the church.

And I think my father’s role in it was more of the helper, the builder, the hauler, you know, working with the horses, and actually doing a lot of the heavy work. But I think probably, um, again, because my grandparents were older, I think they were probably more involved in the spiritual end of that than my father was. Not to say that he was not, um, you know, interested in religion, but because he had left home at such an early age and had to find his way and, um, you know, just work so hard, he probably wasn’t as tuned into it then as my mother’s, um, side of the family was.

He was never really, he was never really the, um, churchgoer that my mother was. You know, he believed, he had a deep faith, he believed in the traditions, but as far as actually coming to church, he was not, um, there as much as my mother was. And simply because his excuses that he had too much to do, he was too busy, um, you know, with, with taking care of the farm and so forth.

Um, he would go, you know, for special occasions, but he didn’t attend regularly. And I think my mother was probably more religious than the fact that she liked to go every Sunday. Uh, and did go almost every Sunday, except in the summer.

In the summertime, if you were haying or something, that took precedence over everything, because you had to get that precious hay and deal with that when the sun shone, um, and you couldn’t, you just couldn’t put it off. And so consequently, um, I think it was that way for most of the people in the community, that they all had a real firm belief, but if, if farming or something like that, you know, something came up that was more, um, I shouldn’t say important, but the timing was so that it had to be taken care of just then. Um, that was where their first priority was, because that is what kept them, um, able to feed their animals and, you know, make their life prosperous.

So that, that is a given. And I think, you know, that probably was not seen as a sign of simpleness if they didn’t farm. They were just taking care, taking care of business and, and doing what they had to do to, to, to survive.

Because, you know, it was a real struggle, you know, a real struggle.

David: Now, you were the ninth child.

Marion: I was the ninth child in the family.

David: What year were you born?

Marion: Oh, boy, when were I ever born? 1932. March 10th, 1932.

David: So you’ve got a birthday coming up.

Marion: I sure have.

Um, I do, um, yeah, actually I was born right at the start of the Depression. Oh, yeah. During the Depression, actually, because I think it started in about 29.

Mm-hmm. And, um, so, you know, actually, again, when you stop and think about the Depression, we were survivors then. Um, we had the farm, we had farm animals, we had, uh, produce that we grew.

We were able to eat well. Uh, we lived very well. I can remember, again, back in the 30s, um, back in the…

[tape ends]