This is the story of a man named John Partridge Bull, an 18th-century blacksmith and gunsmith. He left a few traces in his lifetime, which began in 1731, and ended in 1813. In some ways, Bull was typical of other craftsmen of his period, and atypical in others. Finding out more about his life using surviving evidence can help us to learn more about his community (Deerfield, Massachusetts), his times (mid-1700s to early 1800s), and his place in history.

Biographical histories of famous individuals are common. Less common are biographies of what historians often refer to as “the middling sort” of the 18th and early 19th centuries—people who were neither wealthy nor poor. They were generally farmers or, in the case of John Partridge Bull, craftspeople (also referred to as artisans.) More has been written about professionals such as lawyers, physicians, and ministers, since their record keeping was more prolific and generally more likely to have survived to the present day. Craftspeople, although well-known in their communities in their own time, have been somewhat forgotten and thus have often been slighted by scholars. When historians refer to them, it is often impersonal, as numbers or averages in social and economic studies.

This is rather an oversight. After all, it was craftspeople who (literally) built New England. Better understanding the work these people did and, if possible, what they were like as individuals helps us to find out more about their craft, what their communities were like, and the time period in which they lived and worked. That said, documentary evidence is thin or non-existent for many craftspeople. Fortunately, John Partridge Bull (1731-1813) left an account book full of information about his business transactions from 1768 to about 1788, a fascinating period in Deerfield’s and the nation’s history.

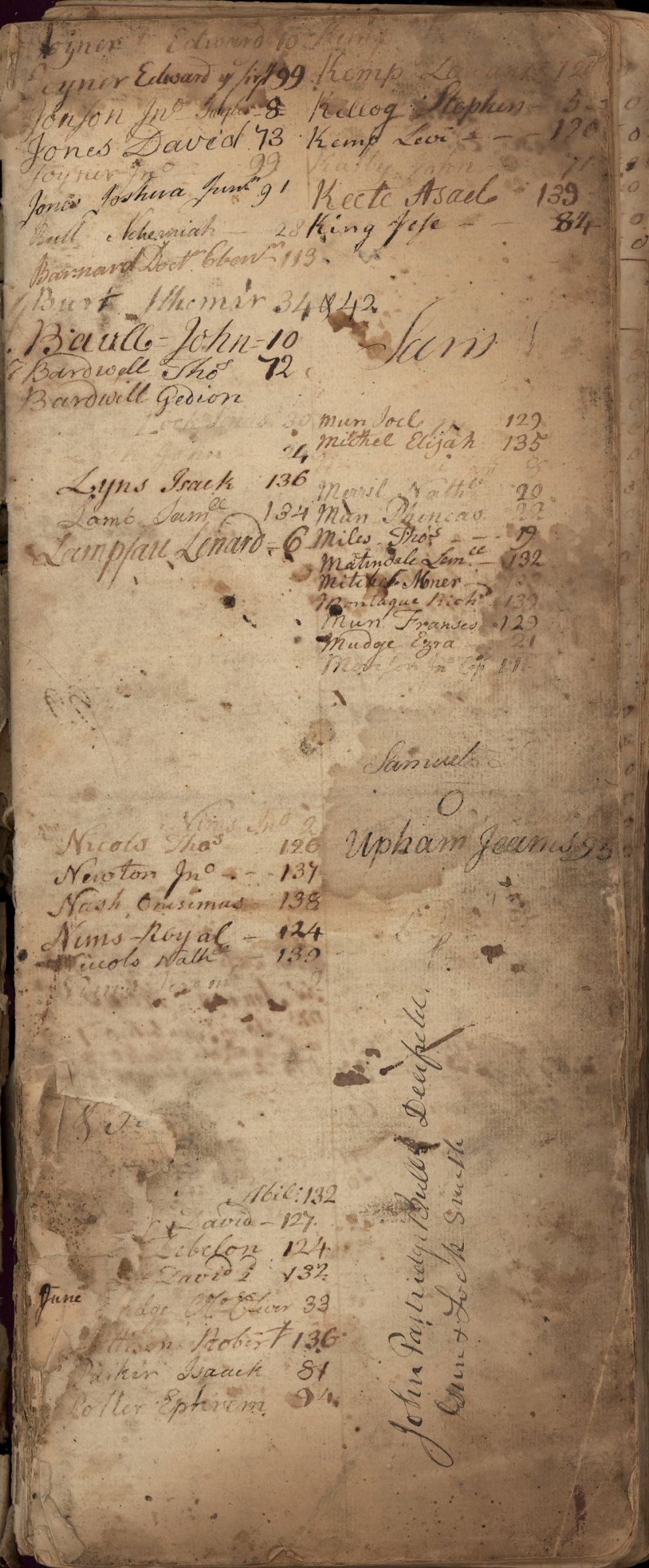

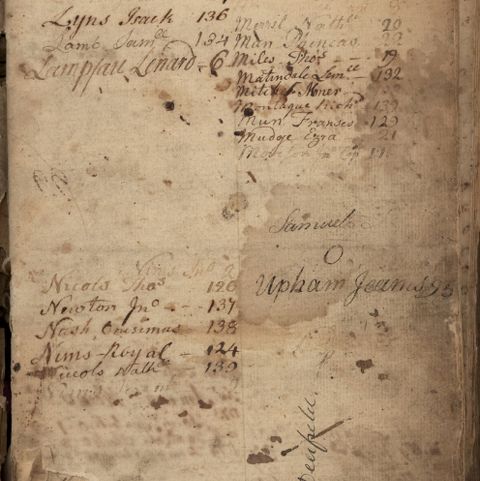

Bull’s house still stands in the village of Old Deerfield, but he left no will and there was no inventory of his estate upon his death. However, his account book, surviving land records, probate files of relatives, town records, genealogical information, and his appearance in other Deerfielders’ account books (including his record as a consumer) all shed light on his life. These sources reveal details about his skills as an artisan, what he made, and how he interacted with others in his community and beyond.

An 18th-century account book provides a portrait of a business. In the case of artisans, account books reveal not only what the artisan made and how they were valued, but also who their customers were (and who they were not), what they ordered, and how they paid (or did not pay.)

John Partridge Bull’s earliest years did not prepare him for the career of a blacksmith. His childhood did not include helping a parent or other male relative at the forge. His father, Nehemiah Bull, was a minister in Westfield, Massachusetts, who graduated from Yale College in 1723. His mother was Elizabeth Partridge, daughter of the Reverend William Williams, the prominent and prosperous town minister in Hatfield, Massachusetts. John P. and his three brothers were raised in what was for that time and place an elite household, and were educated by tutors from the age of four. An inventory of the Reverend Bull’s estate taken after his death at age 39 provides a window onto the material world of the Westfield minister and his young family. In addition to enslaved people–“three Negro maids”—and real estate above and beyond his homelot, the Reverend Bull’s possessions included five bedsteads, numerous chests, tables, chairs, a writing desk, and seven hives of bees.

When the Reverend Nehemiah Bull died in 1740, his sons’ lives were set on a different course than might have originally been intended. Nehemiah had appointed two executors: his “dear and loving wife” and her only brother, Oliver Partridge of Hatfield. Bull instructed them to sell the Westfield house lot and buildings. The money was to be used to discharge his debts and to maintain the widow “so long as she shall continue my widow and what remains thereof afterwards to be divided equally to my children.”

Bull’s will spelled out his hopes and his expectations for his oldest child:

… that my son William get well Educated in the Lattin Greek, tongues of Natural Philosophy and when he comes to be of A Suitable age to live with a Doctor and then he be put to some Skillful Physitian

The minister’s wish for William’s younger siblings provides a tantalizing early clue to the life of the future blacksmith:

and that my other Children be well educated for such Imployment as shall be found agreeable to their Genius and Disposition.

Where did the family go after Nehemiah died? His widow was in her mid-30s, the four sons were aged 11, 9, 7, and 2, and there was a daughter, age 5. A clue appeared in the deed recording the sale of the Westfield house in 1742. It described the sellers as Oliver Partridge and Mrs. Elizabeth Bull, “both of Hatfield.” Elizabeth Bull probably had taken her young family to Hatfield to live with her mother and her brother Oliver and his family.

There are no known sources regarding John Partridge Bull for the next several years. Surviving records suggest that he likely apprenticed with Seth Pomeroy (1706-1777) of nearby Northampton, Massachusetts. Pomeroy was the pre-eminent gunsmith in all of Western Massachusetts, descended from a long line of gunsmiths beginning in Dorset, England in 1636. While his apprenticeship contract, or indenture, has not survived, Bull’s name appeared along with 28 others in a list of militia men “who went to Deerfield August 1748” under the command of Lieutenant Seth Pomeroy. It would be logical for Bull to enlist, at age 17, to serve under a man whom he already regarded as a leader. Bull’s appearance in Pomeroy’s account books confirmed his continued presence in the area and his relationship with the gunsmith.

By 1752, Bull was 21—legally an adult under the law—and probably ready to start up his own blacksmithing business.Custom and common sense dictated that a craftsman not set up his business in the same town as the master under whom he had apprenticed. Pomeroy was still active in the trade and had two sons who were in line to own the Northampton gunsmithing shop. John Partridge Bull had to find a place where his skills were needed. That place was apparently the Salisbury Hills of Western Massachusetts. By 1754, he was doing business with people in Sheffield and other Berkshire County towns, although he did not end up settling there permanently.

The following year, Bull joined a militia company of Deerfield men in the final French and Indian War (1754-1763), again under the command of Seth Pomeroy. Colonel Israel Williams, a prominent Hatfield resident and leader of the powerful Williams family, appointed 24-year-old Bull as Armorer to Colonel Ephraim Williams’s regiment. In the same company were two more members of the Williams family from Deerfield: Dr. Thomas Williams, the surgeon, and Elijah Williams, the commissary. As the armorer, Bull’s job was to keep the small arms in good repair; in other words, any weapon smaller than a cannon. It was a tribute to Bull’s expertise to be placed in such a position and perhaps a nod to his kinship connections to the Partridges and the Williamses.

Bull marched with Pomeroy to Albany, New York on May 31, 1755. From there, his company traveled in July with other New England regiments to Lake George, New York. English military commanders were eager to go on the offensive by taking the war with the French to Canada. In Massachusetts, Governor Shirley was planning an expeditionary force against the French at Crown Point, New York, on the shores of Lake Champlain. A British victory at the lake would help secure the frontiers of northern and western Massachusetts.

A well-laid ambush by French troops and their Native allies on September 8, 1755, proved disastrous for the colonial forces. Many were killed, including Colonel Ephraim Williams, in what became known as the “bloody morning scout.” Lieutenant Colonel Seth Pomeroy was Hampshire County’s only surviving officer. The survivors returned home in November and Bull’s tour of duty ended December 10, after 36 weeks and five days.

John Partridge Bull reenlisted again in April, 1756. His name appears on a list in the back of the account book kept by Deerfield storekeeper and commissary, Elijah Williams. The same document noted supplies issued by Williams: 1 lb. of gunpowder, 1 lb. of lead, and 3 gun flints. The militiamen themselves generally supplied their own firearms and were issued the ammunition. There were 40 men on the account book list, 13 of whom were from Deerfield. Bull committed to serving until October 18, and Colonel Israel Williams appointed him as armorer for a line of forts built to protect the northern and western boundaries of the Massachusetts Bay colony.

Bull was apparently not stationed at the forts, however. The account book of storekeeper and military commissary Elijah Williams, dated June 7, 1756, states, “John Partridge Bull began to bord.” Within three weeks a debit entry appeared, a purchase of nails to “Bull’s shop.” It would seem he was working as an armorer in a shop on Elijah Williams’s land facing the village common.

John Bull had an active account at the store. In the first two months he bought 68 files — one of the major necessary tools for a smith. He also purchased 13 ounces of brass, useful for gun fittings. Young and single, his accounts show he purchased brandy, flip, punch, and wine several times a week. Bull also purchased material for clothing, plus thread and buttons that he would take to the local tailor, John Russell, to make into a coat and breeches.

Bull’s enlistment ended October 18, but he reenlisted the next day for what would be his last military service. Purchases recorded in Elijah Williams’s account book confirm he was in Deerfield at least 15 days of each month. When his military career ended on January 23, 1757, Bull had served 18 months over the course of nine years: from 1748, age 17, to 1757, age 26.

After the war, John Partridge Bull stayed in Deerfield. His decision to settle there reflected his belief that he could prosper as a member of the community, and that the town welcomed a new artisan. Towns like Deerfield would have ceased to exist without a continuous supply of new people, especially qualified artisans. Bull had kinship ties to two prominent families in Deerfield, the Williamses and the minister’s family, the Ashleys. (The Reverend Jonathan Ashley had been born in Westfield and his wife was the half sister of Bull’s grandmother.) A blacksmith played an important role in an agricultural community and Bull’s specialized training as a gunsmith made him doubly appealing. Although there were two other smiths who worked in Deerfield, each had their own specialties, and neither was a gunsmith.

Bull’s making and mending of guns during his early years in Deerfield were recorded in Elijah Williams’s account book, revealing that Bull was working for Elijah and had not yet established his own business. In August 1757, Bull was credited with mending the guns of three different customers, and on the 10th of August he delivered “one Gun Small Sort,” worth 40s or 2 pounds, to Joseph Stebbins (1718-1797), who lived north of the Deerfield common.

By the fall of 1758, Bull was engaged. He was 27, an average marrying age for a man in the 18th century. Elijah Williams’s account book records: “John Partridge Bull left bord October 4, 1758.” The next day, Bull married Mary Catlin, aged 22, of Deerfield. She was the daughter of Captain John Catlin, the officer who had charge of the line of forts extending from Northfield to Pontoosuc. Captain Catlin died shortly before the wedding, but the ceremony proceeded as planned.

The first reference to Bull’s own shop was April 1759, six months after his marriage. An entry in Elijah Williams’s account book recorded that he paid for shingles for “Bull’s shop.” In the same year, Deerfield church records reveal that Mr. and Mrs. John Partridge Bull were admitted to full membership. It appeared the newlyweds intended to make Deerfield their home.

When the town sold land along Albany Road near the common”to accommodate Tradesmen” in the spring of 1760, Bull paid 29 pounds, 6 pence for two parcels. He was 29 years old and now a man of property. Where did he get the money to buy land and build a house?

Bull’s inheritance certainly played a role. On June 12, 1760, he received—after nearly 20 years—83 pounds, 8 pence as his share of his father’s Westfield estate. The delay was due to waiting for Bull’s youngest brother to turn 21 so the estate could be legally divided among the adult children.

Deerfield had prospered in the 1750s, thanks to a demand for supplies to support the war effort. The 1760s were uncertain economically for this town and others in New England in the aftermath of peace between England and France. No one paid their bills to the gunsmith in the 1760s. Cash may have been in short supply, but Bull paid his bill to Elijah Williams in July 1762 with “2 Johannes” — Portuguese gold coins the equivalent of 4 pounds, 6 pence. He also paid his bill “in full” to John Russell, in 1764 and 1768, with 1 pound, 14 shillings and “a pair of tongues” [tongs]. Bull was forced to take out a mortgage in 1768; the document identified a “house, gunsmith or blacksmith shop, and a small barn” as collateral.

In a 1765 Massachusetts census, Deerfield was listed as having a population of 737 people. The town had 85 houses and 123 families, with a White adult population (male and female over 16 yrs) of 375, 17 enslaved African Americans, and 345 children under 16. Northampton, the shire town, 15 miles to the south, had a population of 674, with 203 families in 188 houses.

Although cash in the form of gold and silver was never in abundance in the 18th century, a robust barter system enabled Bull and his neighbors to live relatively comfortably by exchanging goods and services in lieu of cash. His total income recorded in his account book over a twenty year period was 223 pounds, 18 shillings, 8 pence ; 35% of that income was derived from making and servicing guns.

Bull’s best years were in the 1770s, when his gunsmithing tasks increased steadily. Between 1773 and 1780, he made 312 repairs to firearms, mainly to the gunlock, the most complex component of a flintlock firearm. Bull’s list of repairs suggests that although many people owned a weapon in the years immediately preceding the American Revolution, many guns were broken or in need of maintenance:

1771 — 16

1772 — 22

1773 — 36

1774 — 71

1775 — 88

Like his fellow other participants in the rural economy, Bull both owed and was owed money by many of his neighbors. In practice, this mutual indebtedness acted as powerful social cement. Ideally, local debts were always collectible and customers brought in goods, labor, and small amounts of cash in payment. Some incurred debts that were carried forward for years before any effort to settle was made. Like most rural communities, Deerfield was mainly agricultural. Even the most prosperous farmers did not have large amounts of ready cash on hand. Few had the assets sufficient to settle all their debts on demand. For most, economic survival meant not being called upon to settle frequently — or, worst of all, unexpectedly.

In Bull’s case, most of his customers made some effort to settle their accounts in the years of the account book, 1768 to 1788. He collected on 80 percent of his accounts — 190 out of 239 customers made payments. Not all, of course, paid in full. Actually, only 61 of the 190 who paid, settled in full. The most common method of payment was in goods: produce, building materials, fuel, and scrap metal. Food or household products included dairy, grain, fruits, and meat, plus candles, tobacco, and rum. Cash was the medium for only 22 %, or 45 of his customers.

Labor, believed by many scholars to have been the dominant means of payment in this time period, constituted only 6.8 % of the total (16 of the 190 who settled.) Bull probably did not encourage labor as a means of exchange. Unlike most of his neighbors, he was not farming in Deerfield. In addition, he had three sons who were old enough in the 1770s to help him in the shop, and whom he “loaned out” to pay creditors in labor.

During the busy years in his shop, men like Simeon Burt (b. 1733) assisted him. One year, he notified the Deerfield Selectmen that he had “taken into my house John Holden, the son of Caleb Holden, aged 12 years.” (The Holdens were from Pepperell. Massachusetts law required notifying town selectmen of a stranger in your household, as towns sought to ensure that newcomers or transients who fell into poverty would be ineligible for relief based on residency.)

Bull’s life began to change as the American Revolution came to an end and his wife, Mary, died at age 45 in 1782. He devoted more of his time to agricultural work. In addition to the ordinary tasks of mending guns and locks, making a spring for a door lock, and casting a pewter ink pot for Elijah Williams’s son John, Bull also “drove plow” for Williams for 10 days and “took up flax” at Carter’s Land (West Deerfield). Driving the plow for a day earned Bull 2 shillings; he earned 2 shillings, 4 pence to make a fire shovel. “One day’s work in the garden” was worth 1 shilling, 4 pence.

The Bulls sent their oldest son, William, born 1761, to Yale, like his grandfather. William served in the militia in the Revolution. Already trained as a blacksmith by his father, he apprenticed to a physician in Lanesborough, where his Uncle Nehemiah Bull was a justice of the peace. He then became a doctor. John P. Bull continued easing back from blacksmithing and gravitating towards farming. He had no aging parents to consider and his two oldest children, Elizabeth and William, had married. His primary responsibilities were to himself and his unmarried children: Molly, Oliver and Samuel, all of whom were in their 20s. By the spring of 1789, the Bull family had left Deerfield and was established on the 120 acres of land John purchased from the Catlin brothers in the 1760s. It was on the north half of Deerfield’s additional land grant, by then a part of the town of Shelburne. Bull had been listed in Shelburne’s tax list as a non-resident since 1781.

John rented his Deerfield house to Dr. William Stoddard Williams, who recorded in his daybook … “moved my Family into Mr. J.P. Bull’s House for 1 Year April 8, 1789.” For each of the next 5 years, Dr. Williams paid Bull 100 shillings (5 pounds) for the rent of the house. On June 2, 1794, “John Partridge Bull of Shelburn, Gunsmith [sold the house] to Wm Stoddard Williams of Deerfield, Physician [for] 166 pounds.”

John Partridge Bull died on December 24, 1813, at the home of his son, Dr. William Bull of Shelburne. The date is recorded, as was so much of his life, in an account book, in this case that of Dr. William Stoddard Williams of Deerfield. The terse line reads, ” J.P. Bull mort.”