By Susan McGowan, with inspiration from Richard I. Melvoin’s New England Outpost: War and Society in Colonial Deerfield

Why study Deerfield? Because the town is a model for the study of America’s early frontier. Its residents endured 30 attacks in the first 50 years, two of them with devastating results.

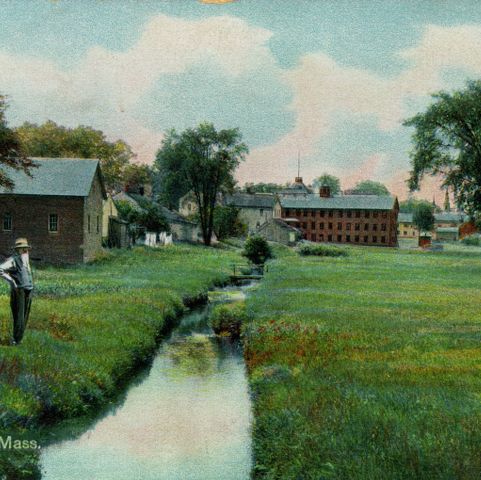

When New England’s lines of settlement, both west from Boston and north up the Connecticut River, reached Deerfield in 1670, they stopped and did not move for 40 years. Deerfield sat on the edge of English settlement for a long time and while it did the frontier dominated its life.

Think of the frontier as “porous” (Colin Calloway), rather than as the “hedge” described by Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 — with trade and interaction between Indian and Indian, English and Indian throughout the 17th century. Melvoin describes this frontier as a zone of exchange between peoples, an area of interaction between cultures. It was fluid and was capable of expanding and contracting.

Three examples: in 1675, friendly Indians dwelled near Springfield even as King Philip’s War began; in the 1710s the Reverend John Williams writes about his “Indian master” coming to visit him in Deerfield; and in 1735, there was a conference held in Deerfield, a meeting between Jonathan Belcher, the royal governor of Massachusetts, and representatives of the Iroquois Nation.

The major force that changed the frontier was, of course, war. That is when the areas of interchange narrow and economic, social, and legal interactions diminish or collapse. Deerfield, as a settlement was isolated. It was not one of a continuous line of settlement linking New England’s frontier. To the north, the east, and the west, there were no neighbors. Deerfield sat alone at “the very tip of a knife blade of settlement” up the Connecticut River Valley. The blade was thin and Deerfield remained alone at the tip for nearly half a century.

Deerfield offered settlers the ultimate risk: it could disappear, and indeed it did, once in 1675 and almost again in 1704. What kinds of people take that risk? Who came?

In 1675 there were about 200 residents. Sixty-eight were adults: 39 men and 29 women. The men ranged in age from 18 to 66; the women varied similarly. Families had on average 5 children. Basically, it was a young man’s town — over three-quarters of the men in town in 1675 were between 21 and 40; the men’s average age was 35 and the women 31. The average age at which a man married was just under 25 and the women were usually 4 to 5 years younger. (These numbers suggest that marriage for men and particularly for women came earlier than in many other New England towns.)

After the battle at Bloody Brook and the abandonment of Deerfield, it was reinvented in 1682. After the 1704 raid, it was once again reinvented, although it had not been completely destroyed this time. Nearly one-half the redeemed captives from 1704 never lived in the town again.

Early Deerfield was as poor as any village in Massachusetts — this is based on county and provincial tax rates and the many petitions for aid from its citizens.

Two major reasons for the poverty:

1. the struggle to survive in the hostile environment took time and energy away from the task of making a living

2. the isolation from resources and markets for trade

As for rugged individualism, another trait that Turner defines as a necessary ingredient for life on the frontier, in Deerfield the frontier drove people together and actually inhibited individualism. In its governance, economics, religion, and social order, Deerfield was inwardly directed, closed, interdependent, and communal. They were, as Melvoin points out, interdependent and beyond democracy, but not “utopian.”

They may have had a vision of what their village could be but they were driven by what it had to be — and in a rough, rude, violent, and unpredictable world.

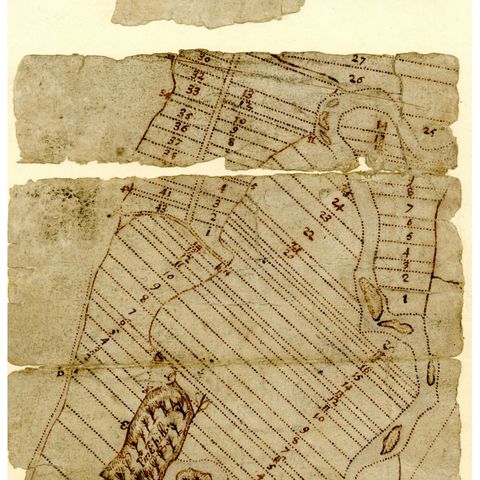

Deerfielders followed English patterns of settlement and the plan resembles a medieval English village.

Their lives were defined by what they could do, where they could do it, how, and with whom. In this sense they maintained not one community but a web of communities. Think of their lives as a series of concentric circles in their relationships with other towns and people…

1. the ring of governance was small and tight and rarely went beyond Deerfield itself

2. the ring of economics was slightly wider, reaching to nearby towns through barter and trade (Northampton was the shire town where deeds were filed, births registered, where the larger taverns were)

3. the kinship and religious ideas and practices stretched further down the Valley (many of the residents had kin in Northampton, Springfield, and towns in Connecticut)

4. the military measures tied them to a wider world — Springfield, Hartford, Boston

Deerfield was alone but it was not hermetically sealed — it was a part of a larger world, even if it was, as Thomas Jefferson later described it, a “three mile an hour world.”

We cannot know how they viewed their lives — but it is hard to imagine that they did not know the risks they were taking by living there. [Robert Hinsdale family]

When the frontier line of settlement moved on after about 1715, with the establishment of the line of forts, the reestablishment of Northfield, and the eventual settlement of the hill towns, Deerfield changed. The people gained security which, in turn, begat continuity… after half a century the town kept a generation of settlers intact and began to see steady growth from within.