The Puritans developed an early government that did not distinguish between civil and ecclesiastical law. The philosophy of the English settlers was manifested in the design of the early meetinghouses. The first New England meetinghouses were square, hip-roofed buildings with a central pulpit to ensure that the participants would be actively involved in worship. Congregants were expected to be able to hear and see the worship service clearly. Deerfield’s first meeting house, built in 1675, was similar to the post office building, which presently is next to the fifth Meeting House. Later meetinghouses were house-like in appearance, and the pew benches were placed lengthwise in the building. Eventually, a steeple was added either on the building itself or on a small addition that was designed solely for that purpose. Deerfield’s second Meeting House, built in 1682, supported a steeple, but nearly spread apart from its weight. During the Federal Period, meetinghouses were often colored with contrasting trim on the windows. Colors ranged between shades of orange, blue, yellow, or brown. In 1729, the third Meeting House was constructed, a far more elaborate structure than the first two houses. Measuring 40′ by 50′, it featured an elaborate doorway, a cupola, paneled boxed pews, a gallery with carved posts, and an elaborate pulpit. The Meeting House also featured a sounding board, often placed above the pulpit to improve the carrying of the minister’s voice. In 1768, the cupola was removed and replaced with a square steeple tower with an open octagonal belfry with a spire. The Meeting House was painted “a dark stone color, the window frames white, the doors, a chocolate color.” The seating eventually changed from pew benches to box pews to provide warmth. Small “heating boxes” were brought by families to warm the enclosed space. More affluent parishioners brought their own cushions and robes as well.

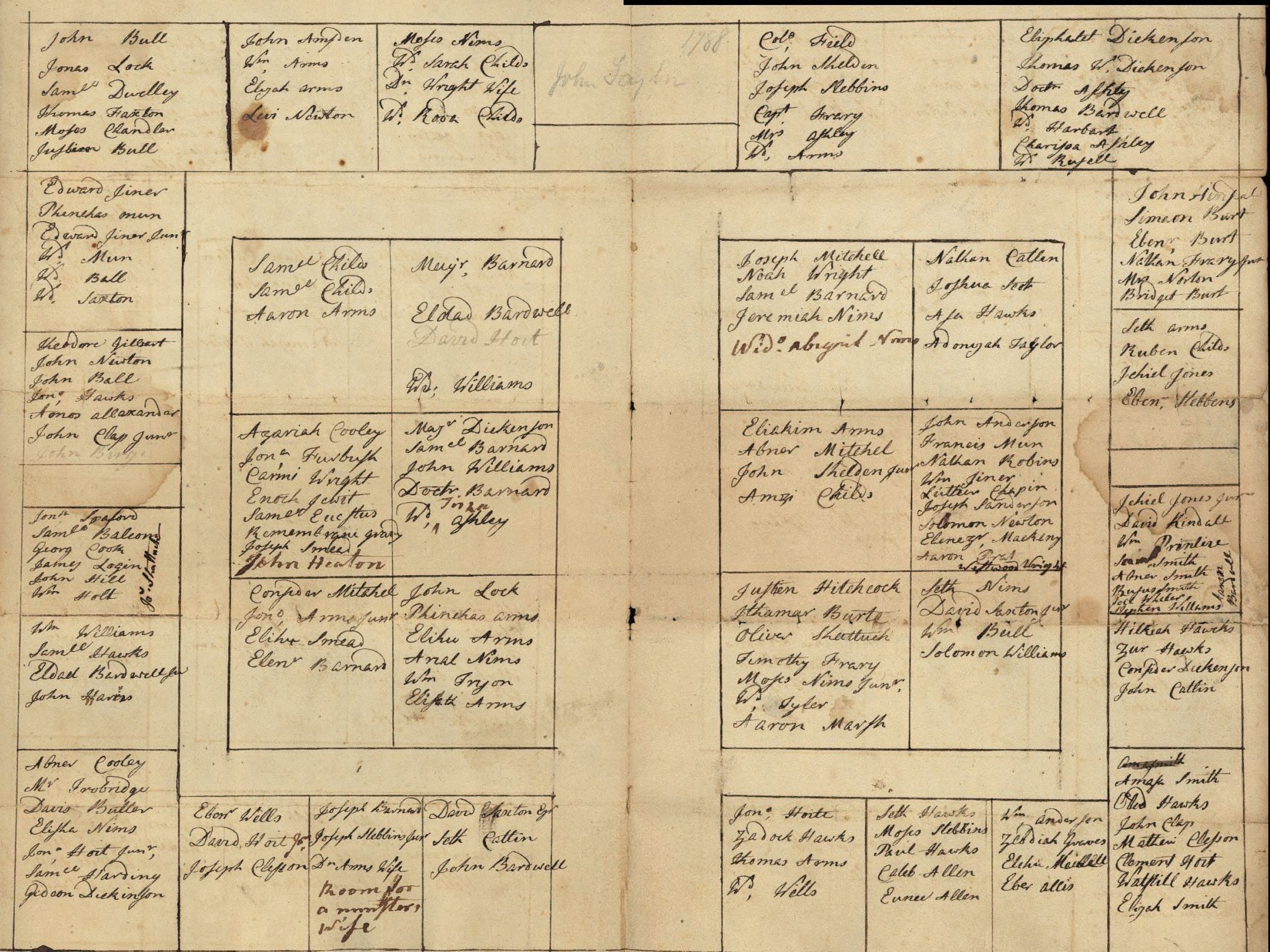

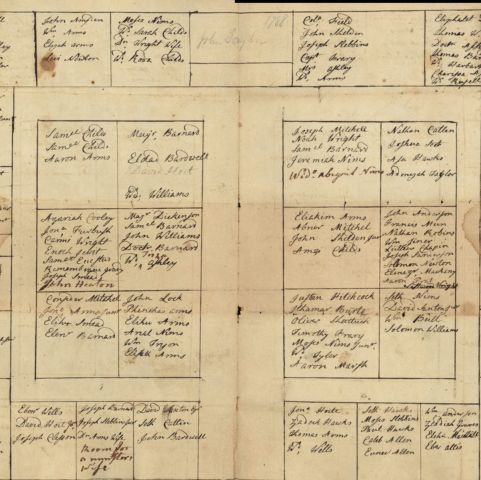

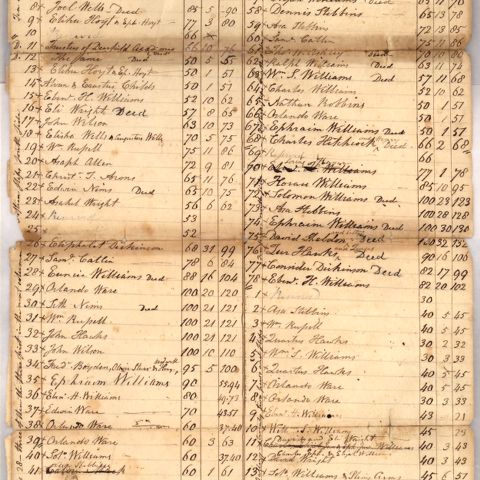

Eventually, the Meeting House pews were once more turned with the pulpit at one end of the edifice, opposite the entry doors. These were often sold to individuals to help with the cost of constructing the building. A seating committee was established that apportioned the benches and pew, based on social status, piety, and age. Documents from Deerfield’s fourth Meeting House illustrate these seating plans.

Taking communion is one of two Protestant sacraments. Once more the sense of community is underscored, as the members remain seated while receiving sacrament. Early communion vessels varied in size and shape, according to the user. Later communion cups of the same size and shape were used, moving away from distinguishing social order in the taking of the sacrament. The addition of lighting and heating was delayed until the early 19th century, when candles in chandeliers, followed by kerosene lamps were introduced. Heating was not introduced until the woodstove with long stove pipes extended throughout the church to radiate heat.

In the Connecticut River Valley, Asher Benjamin, known as the first American-born architect, published from Greenfield. One of his most influential books was, The Country Builder’s Assistant. It greatly influenced the architectural style of the New England Meeting Houses during the Federal Period. These churches were either painted white or were built of brick. Deerfield’s fifth Meeting House, built by Winthrop Clapp in 1824, is in the Federal Style. The meeting houses were centrally located in a community, and used to connote wealth and refinement, each town often striving to build a grander edifice than the other. Over time, following national trends, new denominations came into Deerfield and brought new building styles.