by Susan McGowan

Buildings convey messages, and at different time periods, the messages are different. It is important to remember that in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Deerfield, Massachusetts, and throughout New England, a man’s house was his proudest and his most important possession, a tangible asset to pass on to the next generation.

Dwellings built in one location in one century often bear little resemblance to those built in the same area in another century. Fashion, design, and rationale change. The stoutly-constructed timber-framed story-and-a-half houses of seventeenth-century America, fitted with small windows and with fortified doors, bear little resemblance to the glass-walled constructions designed by architects in the twenty-first century.

The needs and the past experiences of both the housewright and the householder were vastly different between the seventeenth and the twenty-first centuries. Shelter was the major concern of the early European settler in New England. Protection from the weather, from the wildlife, and from the indigenous people was primary to those who settled Deerfield in its early years.

The kind of house one builds is dependent on, in addition to conditions of time and place in which one builds it, the cultural memory of the persons involved. The earlier dwellings, with utility rather than ornament the impetus, were inspired by the familiar – buildings in rural England or in the towns where the residents formerly lived. The woods used were from native trees, chestnut, oak, and pine, both hard and soft. Although often built without decorative additives, there were exceptions. (An extant drawing of 1728 by Dudley Woodbridge and architectural details from the John Sheldon house, built 1699, now in Memorial Hall Museum, illustrate some of the details used.) Verges were sometimes decorated with scalloped boards*; corner boards were attached at each end of the facade and brackets occasionally added to the projecting second floor; doors were embellished with wares made by the local blacksmith – hand-made (“rose-head”) nails and ornamental hinges, latches, and knockers. These details would have been familiar to either the intended owner or the housewright who was charged with the construction of the house, but were probably not found in a published book of plans.

Two-story, five-bay houses (bays = openings across the front of the house, i.e. 4 windows and a door on the first floor, 5 windows on the second), common in New England today, were largely absent from the landscape in the early years of settlement. Rather a story-and-a-half building with a center chimney or a half-house with end chimney was the standard. These unpainted, wooden dwellings were most often sheathed inside with wooden boards. Often dressed with a bead along one edge, the sheathing was nailed horizontally to the vertical studs of the frame against the exterior walls and vertically on the interior walls, where there were no studs. Inside, there were usually two rooms one on either side of the chimney, with an unfinished garret above. One of the downstairs rooms was defined as the cooking room and the other the parlor/bedroom. (Beds were, however, found in every room of these early dwellings.) The ceilings and walls of the rooms were rarely plastered (lime, an essential ingredient for plaster, is absent from the soil in the Connecticut River Valley) but instead revealed the smoothed wooden joists supporting the floorboards of the garret floor.

The early houses were furnished modestly as well, usually with the most basic of possessions – bed, chest, table, chair(s) – but it would not be unusual to find an inventory that included no chest, no table, and no chairs. Floors were bare and many walls were devoid of ornament, save the occasional looking glass, brought from England. Early inventories, taken at the time of the death of a head of household, reveal that the majority of Deerfield’s residents owned few “moveables” or personal property. This would change by the second quarter of the eighteenth century, as the town and its people put behind them the early frontier concerns, including the need to provide constant protection from French and Indian (by the late 1740s the fighting had moved to northern New York and to Canada and the Treaty of Paris in 1763 put an end to the French and Indian wars).

Freedom from fear allowed Deerfield’s residents to devote themselves more intensely to the agriculture that would provide their wealth and improved living conditions. As the eighteenth century progressed, more Deerfield people lived in two-story houses – some with fashionable pedimented frontispieces with double doors, matching window caps (at least on the facade), and exterior paint colors that resembled stone – red, cream, or gray. The earlier simpler structures were either enlarged and “improved” or they were pulled down and replaced with up-to-date versions.

Unlike a painting which, when finished, is framed and hung on the wall and remains virtually unchanged, a house is organic in that it changes and is changed, over time. Buildings are subject to alterations owing to the varying whims and tastes of owners just as the dwellings built in one century often bear little resemblance to those built one hundred or two hundred years later. It would almost seem that houses in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were never considered “finished” as they often contain later additions and extensions beyond the original footprint. Many of them resemble telescopes with their lean-tos and ells stretching out from the original house in several directions. Not only were additions made, but adjustments to existing features were made, too. Doorways were enlarged or diminished and sometimes surrounded with elaborate moldings; as glass became more available and less expensive and as the landscape was tamed the windows were often made larger and more numerous. Roofs were changed, not only by the material used, but often the profile, too, was altered – pitched roofs common to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were transformed or replaced by gambrels by the mid-1700s and to the more shallow hipped roofs, which became fashionable in the nineteenth century.

Chimneys, too, were changed. The large center stack, vital as the source of multiple fireplaces, gave way by the third quarter of the eighteenth century, to two end [back] chimneys, creating a new floor plan with a center passage. Soon after the turn of the century (c.1812) fireplaces were made more shallow and fitted up with iron stoves, the current, more efficient heating method. The stove was slower to be adopted in rural areas, where firewood was not in short supply as it was in cities. Stoves use about one-third less wood than a hearth.

More choices were available for the house interiors, including the use of plaster for the walls and ceilings. The white walls served to enhance the light admitted by the larger windows. Wallpaper, either imported or of domestic manufacture in large American cities, was fashionable and available by the end of the eighteenth century in Deerfield. As an alternative to papered walls, free-hand or stenciled wall decorations were advertised by itinerant artists. Specialized forms of furniture began to appear; no longer were the forms confined to the earlier bed, chest, table, and chair(s). Card tables, wash stands, high chests, matched sets of fancy, painted chairs all were offered by both urban and rural furniture makers and owned by families in Deerfield. Floors were often covered with canvas floor cloths or imported woolen carpets and the windows might be dressed with fabric or the fashionable slatted curtains, known also as “Venetian blinds.” Consumerism and the resulting increase in household goods ultimately caused housewrights to begin to include closets in their building plans.

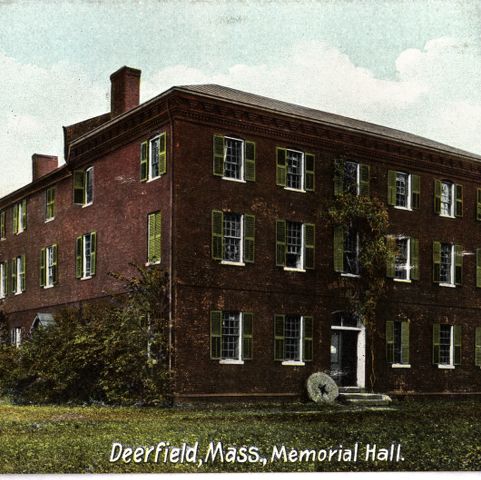

As the frontier mentality passed, English pattern books were consulted for house plans but especially for ornamental details, both on the exterior and the interior of houses. Examples may be found from published books by Batty Langley, William Pain, and others. It was not until 1797 that an American book of architecture was available. Asher Benjamin published, in Greenfield, Massachusetts, The Country Builder’s Assistant, a book containing designs translated from other published sources intended to provide, as stated in the title, assistance to local builders. A number of houses in Franklin County, several of which are in Deerfield, Massachusetts illustrate examples of details published in Benjamin’s first book and in the six books which followed over the years. Memorial Hall, the first building of Deerfield Academy was designed by Mr. Benjamin in 1797, and was the first masonry construction in the county. It is now open to the public as Memorial Hall, the museum of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. Soon after the opening of Deerfield Academy in 1799, a brick dwelling house, a domestic version of the Academy building, was constructed on the Deerfield Street, adding variety to the many frame dwellings on the landscape.

In general, the cultivation of the landscape as provider of foodstuffs was the major use of the outdoors in early New England. Land was used to produce something to eat or drink and a house was built into the landscape “as it lay,” minus the kinds of adjustments to the elevation we are accustomed to today. By the nineteenth century there is evidence of ornamental plantings to embellish the house site, as well as carefully crafted garden plans (Dr. Stephen West Williams, 1823; John Wilson, 1845). More attention is paid to the creation of a setting for the dwelling house than before. Throughout the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth, before the advent of cars, boats, and impressive stock portfolios, a man’s house and property remained his most treasured possession.

*Projecting board placed against the incline of the gable of a building and hiding the ends of the horizontal roof timbers.