Horace Mann (1796-1859) changed the direction of the Massachusetts school systems. As the first Secretary of the State Board of Education and an early reformer, he championed free public education as a means to combat social ills. Soon after he was appointed he learned that in Massachusetts the more affluent families were sending their children to private institutions. The free schools were left in a state of disarray, with limited financial support, untrained teachers, substandard and unsanitary buildings, and uneven courses of study. Philosophically, Mann believed the mission of the school is to bring into balance the body, the intellect, and the spirit of the child. He believed in moral education without a basis in religion, in a disciplined, but not authoritarian learning environment, and in instruction that lead to problem solving. Furthermore, he believed that the schools should include children of all economic classes. He addressed the issue of untrained and unprepared teachers by working toward the establishment of “normal schools” to instruct them. He worked to extend the school year for at least six months, provided for uniform textbooks and teaching materials, and created school libraries (paving the way for free public libraries in the state).

Influenced by Mann’s concern with hygiene, Massachusetts schools were the first to make physical education and health instruction a mandatory part of the curricula. Following a series of epidemics, medical inspections of Boston schools began in 1894. In 1906, Massachusetts adopted the first statewide medical inspection law. In the early 20th century, the health movement expanded to include physical examinations, eye and ear tests, and hygiene instruction. It interfaced with the emphasis on physical education.

Further, Massachusetts education initiatives included the first English-speaking kindergarten, opened in 1860, in Boston by Miss Elizabeth Peabody. This initiative proved successful and in 1868, a training school for kindergarten teachers opened in Boston under Miss Peabody’s influence. Training in the manual arts was another part of 19th century education reform. It began in 1880, as a highly technical type of high school instruction available only to boys. In 1885, courses in household arts, designed to provide girls with the education formerly offered by their mothers or private schools for young ladies, were introduced. Both types of training began in New England and moved west. By 1875, math and book science were taught in high schools and academies throughout the country, followed by the development of laboratory science.

John Dewey (1859-1952) was another prominent name in education. He advocated for a practical application of training, connecting school activities with life experiences. Dewey believed that children learn by doing. In school, they should be taught to have initiative, to meet responsibilities, and to develop socially.

Alfred Binet (1857-1911) sought to give gifted children special attention. The Stanford-Binet test was used to theoretically determine the intelligence of students.

In the 1870s, before child labor laws were enacted, a special type of education was provided for children who were working in the mills. These “half-day mill schools” existed for a brief period in five Massachusetts cities: Lowell, Salem, Fall River, New Bedford, and Springfield. Children were expected to attend classes in the middle of their day and then return to work. Mill owners saw this as an investment opportunity. The children’s skills improved and their production increased.

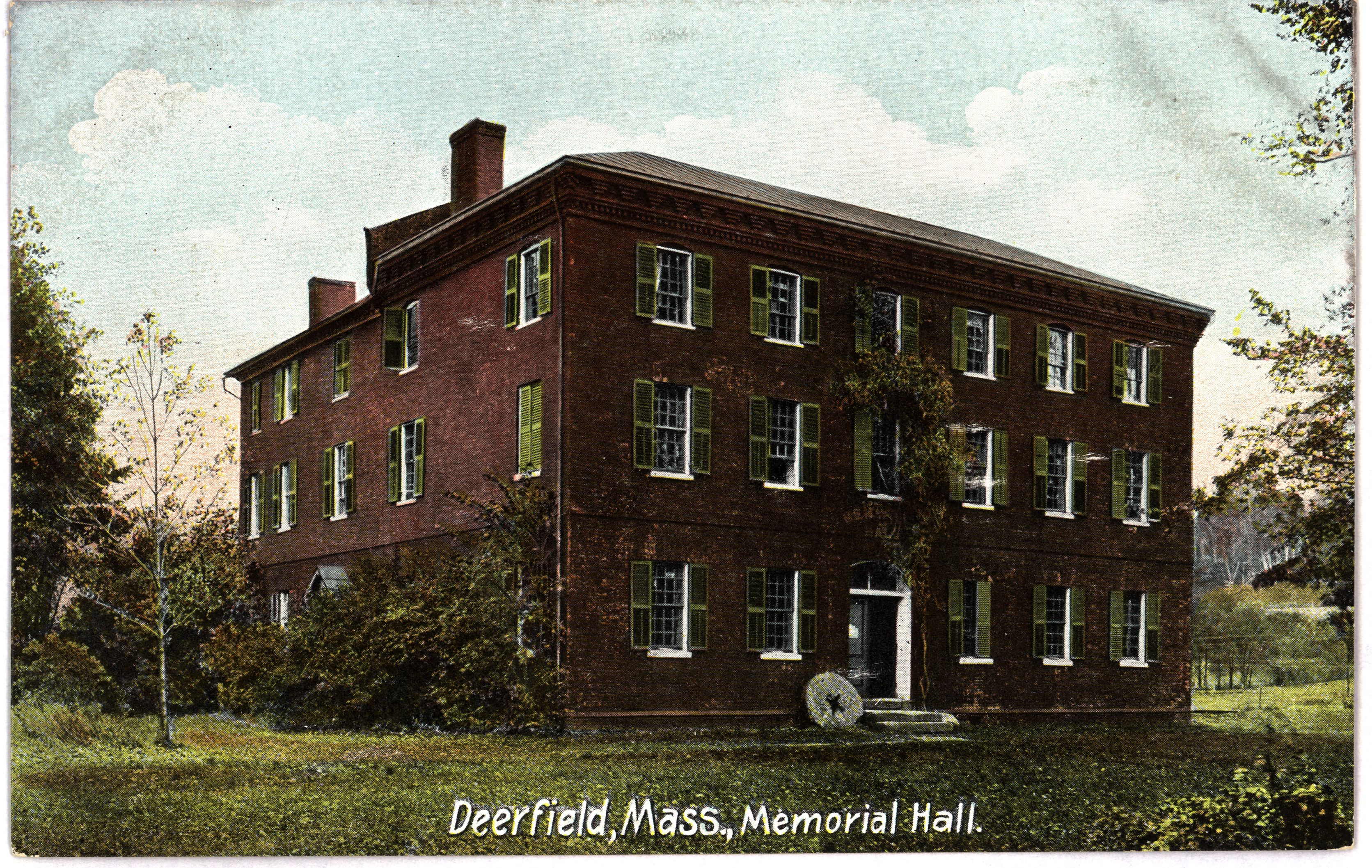

Deerfield has had a long history of fostering education, beginning in the late 17th century when the religion in New England mandated that all children receive some education so that they could read the Bible. Deerfield Academy was founded in 1797. The next year, noted architect Asher Benjamin was hired by the new school to design and construct the brick building on Memorial Street it would call home for nearly 80 years. In 1878, the former Deerfield Academy building became the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association’s Memorial Hall Museum. One of the association’s missions was to educate about the early settlers of Deerfield.

The early 19th century brought with it a split between church and state and education became more secularized. Regulations for governing Deerfield’s schools were voted on at town meetings. In May of 1817, these regulations:

- provided for an annual meeting, held in March, when new candidates for the position of instructors would be presented. The school committee would reveal information about each candidate’s literary qualifications and moral character;

- empowered the minister and two of the selectmen to hire instructors. The three were then charged with visiting the school twice a year;

- required that the instructor keep records of student attendance, study, and behavior;

- required that an instructor regulate the voices in reading;

- required an instructor to proceed in a gradual way in teaching to prepare the way for the next degree of difficulty;

- required that vocabulary be taught as early as possible, but without teaching students words that they were unlikely to use;

- required that the most important courses be spelling, word definitions, reading, writing, and arithmetic, followed by geography;

- required that review of lessons be frequent;

- required that no one be asked to write until age seven;

- required the instructor to keep students’ written work, to be exhibited to the visiting committee;

- required that the old English system of pounds and shillings no longer be taught;

- required that attention be paid to the inculcation of good morals and manners;

- required that lessons on instructive parts of the scripture be read twice a day;

- required that the school open and close with a simple prayer;

- required that “scholars” who were able to read have one lesson each week in some approved catechism.

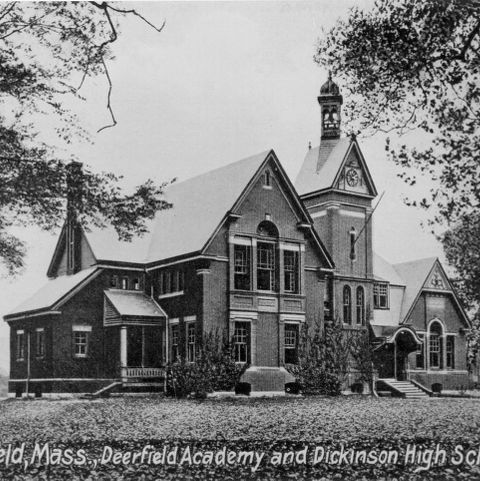

When Esther Harding Dickinson died in 1876, her will provided funding for the new Dickinson Academy and Deerfield High School. The new building, containing a reading room and free library, was constructed on the Dickinson homelot. Both boys and girls attended this college preparatory school.

In 1913, a new brick school building was opened on Main Street in South Deerfield to meet the growing student population. Three previous structures had served the town, the earliest of which was constructed in 1800. The new building had a playground, a modern heating system and up-to-date sanitary facilities. The new curriculum included physical training and hygiene instruction, as well as providing special attention to those children “whose minds are less active” than others.

Another new school was opened on North Main Street in South Deerfield in 1924. In 1926, the state legislature made the separation between the public and private schools official.