Around the turn of the 20th century, a tide of Eastern European immigration altered the ethnic landscape of Franklin County in Massachusetts – and the entire Connecticut River Valley. 1 Eastern Europeans first arrived in the region around 1890, with their presence increasing throughout the next two decades. In 1890, 90 individuals from Poland lived in Franklin County; by 1900, the number had grown to 716 people from Austrian Poland, German Poland, and Russian Poland combined. By 1920, 2,006 individuals born in Poland lived in the county, comprising approximately 4% of the population.2

Newcomers from Eastern Europe were most often rural lower-class residents, displaced by land redistribution efforts employed after the abolition of serfdom. While suffering from poverty and overpopulation, many people also experienced religious and cultural oppression, sometimes through legal measures and sometimes through violence. Many landless residents migrated from the countryside to the cities in continental Europe, either around their homeland or in nearby industrializing Germany. There they worked in factories or in mines before traveling to the U.S. The hope of higher wages and greater security often pulled them to the harbors of New York or Baltimore.3

Most of the Eastern European newcomers to the U.S. were among the poorest ethnic groups entering the country. Lack of money prevented many from moving out of the port cities where they first arrived, or the transit centers through which they passed, and many found industrial jobs in these locales. However, the story of Franklin County reveals that some Eastern Europeans eventually landed in rural areas where they worked as agricultural laborers. Nationwide, only 10.9% of Eastern Europeans worked in agriculture, but in Deerfield, Massachusetts, the percentage was much higher at 83.6%4

Although many newcomers originally intended to make enough money in the U.S. to return to their native lands, the situation in the primarily rural Franklin County was different. Some newcomers to Deerfield probably worked for a time in New York or another Eastern industrial center, or in the mines of Pennsylvania, before coming to this area. Those first to arrive were likely recruited by labor brokers seeking farm hands for Connecticut River Valley farms after the catastrophic Civil War and booming urban areas reduced the area’s population. 5 The newcomers worked in labor-intensive onion and tobacco fields, crops adapted as bigger farms in the Midwest took over corn and wheat production and made New England’s small-scale farming unprofitable. According to one study, two labor brokers claimed to have brought 9,000 individuals to New England for work in mills or agriculture in 16 years.

Coming from many sprawling empires and a multitude of provinces and small villages, this new wave of immigrants practiced a variety of religions, spoke different languages, and harbored varied loyalties and prejudices. Diverse as they were, individuals were often referred to en masse as the “Poles” in Western Massachusetts newspapers and even census records. That the immigrants themselves at times embraced the generalized term on their own accord created a sense of shared identity among individuals from very different backgrounds united in their “foreignness.” 6 The grouping of all Eastern Europeans into a pot called “the Poles” provides insight into the way “ethnicity” is formed, and how lines of nation, town/village, and region seemingly disappeared amidst the Eastern European newcomers to Franklin County.

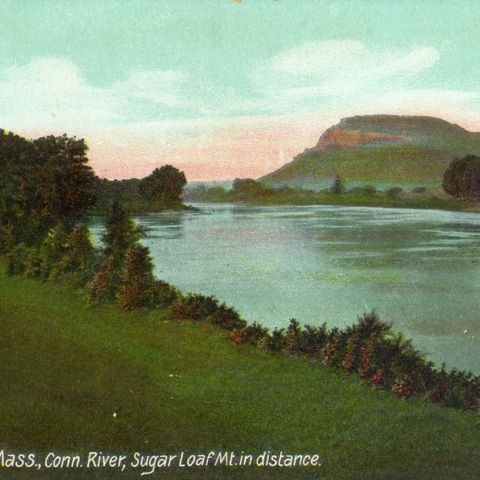

While some immigrants found work in the mill towns of Holyoke, Springfield, and Turners Falls, many turned to agricultural jobs in the rich fields along the Connecticut River. 7 These newcomers were not always warmly welcomed or appreciated. “Nativists”- White people born in the United States- felt threatened by “outsiders” whose languages, religions, foods, and lifestyles differed from their own, and in New England it was feared that “Yankee” culture would eventually be subsumed. Nativists from the East Coast through the Midwest attempted to preserve a pure, “American” past, an idyllic and constructed local and national history stressing Protestant virtue and Anglo-American progress. 8 Across the country, nativism took varied forms, from acts of violence and terror to refusal to hire or work with immigrants.

While Eastern Europeans were praised in some Western Massachusetts news articles from the time for the tremendous labor they put into cleaning up abandoned farms and turning them into tidy, productive businesses, they were also negatively stereotyped in other articles as being lazy, slovenly, lacking in intelligence, unable to speak English, and refusing to conform to Yankee ways. In addition they were Catholics in a land of Protestants. Silences in works like George Sheldon’s History of Deerfield -written as the Eastern Europeans’ presence was first being felt in the community – illustrate that some nativist Yankees worked to deny their entrance into the community.

As in urban areas, initially many immigrants were single men, though single women migrated as well. The men often lived in boarding houses, many of which were eventually run by an immigrant family who could afford to buy a house and rent out rooms. Single women often worked as domestic laborers, learning English and American housekeeping through first-hand experience, and living in the homes of the families they served. Newcomers who arrived alone often married someone from the immigrant community in the area. The work of both partners – both before and after the nuptial – contributed to the new family’s attempts at financial success. Together the young couple often saved enough to transition from tenant farming to actual ownership of land, up for sale amidst agriculture change in the area. The new wife would leave her role in domestic service, assisting in the fields and with the livestock, as well as cooking and caring for a growing family. Influenced not only by their Catholicism but by the economic value of many children, large families were common among Eastern European agricultural families. Many hands to help on the farm, coupled with the perceived economic mobility of America, encouraged the large families.9

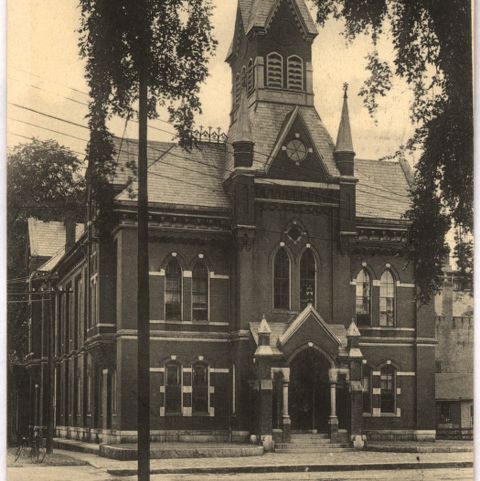

While the family was central to the social and economic organization of Eastern European agricultural laborers in Western Massachusetts, another institution often formed the center of their communities: the church. Many newcomers found established Roman Catholic Churches in or around the communities they settled in – by 1890, Greenfield, South Deerfield, and Turners Falls all had established churches with their own buildings and priests. Around 1910, Greenfield and Turners Falls churches began offering mass in Polish to meet the needs of this new population.

Due to fundraising and building efforts within Eastern European immigrant communities, churches and synagogues began to appear throughout the county. In 1912, St. Stanislaus was completed in South Deerfield, followed in 1914, by Our Lady of Czestochowa in Turners Falls, and in 1920, by Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Greenfield. Jewish families in Greenfield organized a synagogue by 1910, and by 1921, Ukrainian Catholics (Byzantine Rite) had organized a church in South Deerfield.

Places of worship were often the center of social functions and served – through services in the native language and through informal community activities like meals and the observance of holiday traditions – to preserve and transmit the immigrant group’s culture.

Deerfield and surrounding towns in Franklin County, Massachusetts, provide a particularly interesting example of both assimilation and cultural preservation on the part of newcomers and Yankee residents, alike. Once strangers in the land of the Yankees, these newcomers and the generations that followed assimilated to Western Massachusetts and they changed it. One needn’t look far, if driving through Franklin County, to see the evidence and effects of Eastern European immigration on this place. From farm stand and business names to church steeples, their presence and activity through the past is embedded in places and spaces throughout the area, testimony to the way in which they and their descendants continue to shape the landscape and culture of the Connecticut River Valley.

Footnotes

- See Hilda Golden, Immigrant and Native Families: The Impact of Immigration and the Demographic Transformation of Western Massachusetts, 1850-1900 (University Press of America: New York, 1994), and Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Ethnicity and Immigration in American Life, (Harper Collins: New York, 1990).

- An extensive and thoughtful discussion of the background of Polish immigrants to America is found in Golab.

- See Blejwas, and also Long, Grady, “Agricultural Labor Brokers of Eastern European Immigration to the Connecticut Valley” (Deerfield, MA: Summer Fellowship Program, 2000).

- See Miller & Lanning; also see John Higham, Strangers in the Land.

- Long, “Agricultural Labor Brokers”

- The use of “the Polish” as the label for all immigrant groups is widespread in articles in the Greenfield Gazette & Courier, in articles including “Are we to be Polanized” (5-19-1900, p. 4) and “Aliens in New England (12-7-1912, p. 7), and in publications including New England Magazine’s “The Pole in the Land of the Puritan,” (Vol. 29, 1903/04). Discussions of this from a second-generation immigrant’s perspective are found in Marilyn Kuklewicz oral history interview 1, PVMA Collection, transcript pages 10-11; and William Kostecki oral history interview, transcript page 1. For more on how ethnicity is created by both immigrant groups and those native to their new destination, see Kathleen Neils Conzen et al, “The Invention of Ethnicity: A Perspective from the U.S.A.,” Journal of American Ethnic History (Vol. 12, No. 1, Fall 1992).

- See the Massachusetts Entry within the U.S. Census Records for the years 1880, 1890, 1900, and 1910, United States Historical Census Data Browser (http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/census/), published by Inter-University Consortium for Social and Political Research. Also see Long, “Agricultural Labor Brokers,” (FINISH ENTRY).

- For more on nativism, Higham, Strangers in the Land. The newspapers of the period attest to the use of nativist language but do not suggest, at least in the period 1890-1920 that any vigilante anti-immigrant activity took place. This fits Higham’s thesis that since the turn of the century was a relatively prosperous era for the nation, the immigrant threat did not seem so immediate or dangerous, and thus violent nativist activity did not take place. This stands in contrast to the precarious 1850s as the Irish flooded American shores, or in 1920, as the nation’s economy dipped after the Great War and the KKK revived nationwide with vigor.

- An excellent overview of all the churches of Franklin County is in Irmarie Jones, Franklin County Churches (Greenfield Recorder 1983).