O Tempora! All nature seems to be in confusion; every person in fear of what his neighbor will do to him. Such times were never seen in New England.

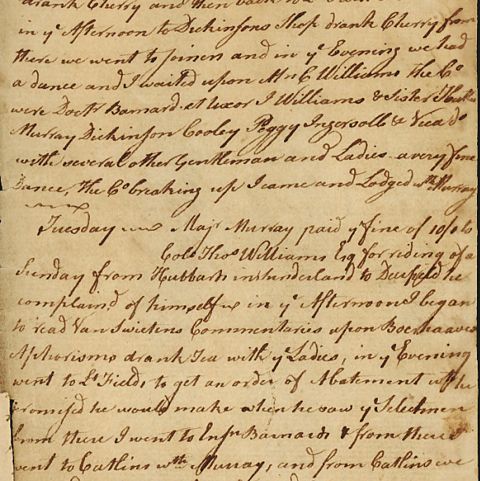

Diary entry of Elihu Ashley, a 23-year-old physician’s apprentice in Deerfield, Massachusetts. PVMA Collections

What was life like in a village in the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts on the eve of the American Revolution?

For many Americans, the Revolution evokes images of tea floating in Boston Harbor, well-behaved gentlemen in knee breeches and buckled shoes politely disagreeing with Parliament and sending along petitions, followed by a perfectly crafted Declaration of Independence, and in due course, the United States Constitution.

Of course, the reality was far more complicated and the outcome much less certain. The American Revolution was a grass roots movement that both divided and united communities. The issues of the day engaged poor and wealthy, African Americans both free and enslaved, Indigenous people, indentured servants and apprentices, women and children. Strife between neighbors and even family members intensified as relations between the British Parliament and the American colonies rapidly deteriorated in the 1760s and 1770s. Patriots, Tories, and people who did not want to choose a side endured political and social upheaval years before the war began in Lexington with “the shot heard round the world.”

Before the American Revolution, Western Massachusetts had been contested territory. Generations of Deerfielders actively participated in multiple wars, including conflicts with Abenaki and other Indigenous people resisting incursions into their territories. Deerfield militia fought alongside British soldiers as England and France struggled for control of North America. In 1763, Britain won the final French and Indian War, reducing France’s North American possessions to islands in the Caribbean, and creating a British Empire larger than that of ancient Rome.

The price of British victory was a crippling war debt. To service that debt and pay for administering and maintaining its expanded empire, Parliament laid heavy taxes in England and its colonies. The British government taxed legal documents, playing cards, and other paper products (Stamp Act), and imported goods like glass, paint, lead, and tea (Townshend Acts). These policies triggered outrage and resistance, dividing colonial legislatures, communities, and families in the process. Tensions between Loyalists (aka Tories) and Whigs (aka Patriots) escalated throughout Western Massachusetts on the eve of the Revolution.

People in the mid-Connecticut Valley were slower to protest and resist than Boston and other eastern towns, at first. The Stamp Act, unpopular as it was, did not rouse anything near the level of unrest and violence in Western Massachusetts that it unleashed in Boston and other coastal cities throughout the mainland colonies. But, there were signs that the traditional political and social consensus was beginning to break down. Community divisions were particularly severe in Deerfield, where the town was about equally divided between ardent Whigs and equally fervent Loyalists.

1770

A Deerfield resident who was a young child in 1770 vividly recalled how residents reacted to the Boston Massacre. “The massacre, as it was called, in King street (now State Street) Boston” was “probably rendered more distinct from a hand bill containing an account of the affair, pasted up in the bar room of my father’s house then kept as a tavern. Part of the description was in Poetry and well calculated to rouse the spirits of the people.”

In the same year, the town began sending new representatives to the Massachusetts General Court, or Legislature. During the previous 10 years, Deerfield had chosen Elijah Williams and Jonathan Ashley, Jr. to represent their town. The Williams and Ashley families were among the region’s seven prominent and interrelated families. They, known as “Mansion People” or “River Gods,” wielded social and political influence up and down the Connecticut Valley. Both Elijah Williams and Jonathan Ashley were strong supporters of British authority throughout the 1760s and 1770s. Choosing to send David Field to the General Court signaled the eroding status of those traditional elites and a breakdown in political consensus. Field strongly opposed Britain’s colonial taxation policies. Members of his family and other Whigs would assume greater authority and prominence through the 1770s as the fortunes of the Williams, Ashley, and other Loyalist families began to decline in Deerfield and other Valley towns.

1773

In 1773, Deerfield sent a committee to Northampton, the shire town 15 miles to the south, to consult with Quartus Pomeroy, blacksmith and bell maker, about mending the meetinghouse bell. The town instructed the committee to ask Pomeroy whether “he thought it could be mended or should be sent home.” By home they meant England, a reminder that, in 1773, American colonists still considered themselves English subjects.

In the same year, the Whigs again prevailed and voted in another Field. This time, they elected David Field’s son, Samuel, to the Massachusetts General Court. That John Williams and Jonathan Ashley, Esquire were out and the Fields were in confirmed traditional lines of power and authority were being repeatedly and often successfully challenged by the Whigs in Deerfield and other communities across the Commonwealth. Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson refused to convene the General Court as it was dominated by self-proclaimed Liberty men like Field. Hutchinson also sent men friendly to the government to canvas opinion and bolster support. They came to Deerfield where Loyalists entertained them at Major Seth Catlin’s tavern. He was a veteran of the French and Indian Wars and an outspoken Loyalist. None of this helped soothe the suspicions and anger of the Deerfield Whigs.

By year’s end, the political situation took another turn for the worse when Patriots dumped 92,000 pounds of tea into Boston Harbor on December 16, 1773. Once again, reactions in Deerfield were mixed. Liberty men celebrated the dumping of the tea while the more conservative condemned the destruction of property and mourned the breakdown of law and order. Epaphras Hoyt recalled,

“The Tories resorted to the public house of David Hoyt and the Whigs to that of David Sexton. The destruction of the tea was a joyful theme of exultation. After getting a little warm on the subject or something else. They march[ed] in a body thro the street singing

Then they went aboard their ships our vengeance to administer

Boston Tea Party Report, PVMA Collections

And didn’t care a tarnal bit for any king or minister

They made a duced mess of tea in one of the biggest dishes

I mean they steep’d in the sea & treated all the fishes

From then on, according to Epaphras Hoyt, son of the Loyalist tavern keeper David Hoyt, “the parties of Whig & Tory began to be strongly marked.” Benjamin Franklin’s Whig sympathies cost him his job as postmaster general, a position he had held since 1753. As mail service subsequently broke down, 25 Deerfield residents formed a plan to keep up mail delivery in turbulent and exciting times. Each paid William Mosman 12 shillings to carry mail from Boston to Deerfield in 1773, to be delivered to David Hoyt’s tavern at the center of the village. David Field and David Hoyt were among the 25 Loyalist and Whig inhabitants willing to pay to stay abreast of the happenings in Boston.

1774

As punishment for the Tea Party, Parliament ordered the port of Boston shut down, one of a series of punitive measures that became known as the Intolerable Acts. Elihu Ashley, Jonathan Ashley’s younger brother and the son of Deerfield’s minister, wrote mournfully in his journal, “greater Callamities are daily expected.”

Elihu was right. The following month, on July 28, 1774, he wrote in his journal that his friend David Dickinson “came and told me yr [there] was a Liberty Pole brought into Town…” Such poles, dozens of feet tall, were commonly erected in public locations in communities by “Sons of Liberty” to symbolize their opposition to the policies of the British government. In this case, the pole was to be erected in front of David Field’s store. According to Elihu’s entry, Dick dared Elihu to “go and cut it off,… I told him I would if he let me have a saw he went home & got one which I took; and went and sawd it about half off.”

Elihu finished off the job later that same night with help from Seth Catlin and Phineas Munn, Deerfield Loyalists who had little use for liberty poles. The village was abuzz the next day with speculation. Elihu reported he had “heard nothing but Liberty, and ye Poles being Sawd.” On July 30, an anonymous writer posted a letter condemning whoever who had sawn it in half as “some malicious Person, Inimical to his Country.” The same writer noted that the liberty pole been erected again, along with a Tory pole. “Where,” he asked, “are things going, that so sensible people as you the Town of Deerfield are, should suffer these Rascals to carry matters on so. I cannot help feeling, and very sensibly, when I think what the Consequences of these things will be & have no reason to think but that they will issue in blood.” The author of this “anonymous” letter was none other than Elihu himself, who may have written it to deflect rumors that he had destroyed the first Liberty Pole.

Elihu’s worry that the stormy political climate would result in turmoil and bloodshed was confirmed over the coming months. The Massachusetts Government Act proved to be the last straw for Western Massachusetts Whigs. Another of the Intolerable Acts passed by Parliament, the Act forbade any but annual town meetings and handed control of the courts over to a Military Governor, General Thomas Gage. Widespread, organized resistance to the Act erupted across Massachusetts. Angry and alarmed lawyers and court officials watched helplessly as thousands of “Liberty Men” forcibly closed judicial courts in Worcester, Great Barrington, and Springfield, all in the name of “the people.” Deerfielders were once again among those deeply and personally affected by these events.

On August 29, Elihu’s older brother Jonathan, a lawyer, set off for Springfield to attend the quarterly Court of Common Pleas. Just before sunrise the following morning, the Springfield meetinghouse bell rang. This was apparently a signal; a large group of men with white staves marched into the center of town and took possession of the courthouse steps. By 9:00 a.m. over 1,000 men had gathered and their numbers continued to grow. Jonathan Judd, Jr. of Southampton estimated the crowd at two to three thousand, writing in his journal how “They closed the Court and the men formed a circle in the street, rounded up any stray Tories, and one by one they were made to acknowledge the error of their ways … and, further, to sign an agreement not to act under any authority derived from the King.” Moses Harvey of Montague “much abused” an angry Seth Catlin of Deerfield for daring to open the court in his official capacity as a Justice of the Peace and officer of the court. It was a humiliation that Catlin would not forget.

Meanwhile, at home in Deerfield, Elihu endured anxious hours. He restlessly traveled from tavern to tavern hoping for information about what was happening at Springfield and for news of his brother. When a severely shaken Jonathan Ashley at last returned home that evening, Elihu wrote that he had never seen “a person so altered in my Life as my Brother was Entirely without Law, every Man left to the Mercy of his Fellow.” Jonathan Judd echoed Elihu’s sentiments: “Now we are reduced to a State of Anarchy have neither Law nor any other Rule except the Law of Nature…”

As tensions grew, so did animosities and open confrontations between neighbor. The night after the Springfield court closing, a Deerfield mob under the leadership of 25-year-old Joseph Stebbins seized Phineas Munn, aged 38 and an avowed Loyalist, and forced him to “make his confession.” Munn was a cooper and surveyor who, like Major Seth Catlin, had been a soldier in the French wars. Again, Elihu Ashley recorded a firsthand account of the disturbing events taking place in his small community where neighbor was turning against neighbor. Elihu reported that

“S[amuel] Field of Greenfield had gone to his father’s home in Deerfield for protection…he felt very low as he Expected to be mobb’d… The Mobb could not find him but swore if he did not resign himself up they would next Monday night find him if he was to be found. Our Guns, Pistils &c were Loaded, soon Expecting they would come and burst the House…E[lihu] Field, who had been down to see the Mobb, told me they had got Munn, and that he had made his Confession.”

Elihu concluded his entry with words that summed up perfectly the disorder and divisive politics of the year before war broke out in April 1775:

“Oh Tempore, all Nature seems to be in Confusion, every Person in fear of what his Neighbour

will do to him such Times never were seen in New England.”

On September 20, 1774, Deerfield chose delegates to attend a county convention at Northampton to plan responses to what Liberty men believed were the Massachusetts Government Act’s open assault on the constitutional liberties in the colony’s charter. The convention recommended the creation of a Provincial Congress, and that communities defy the despised Act by continuing to hold town meetings. By October 1774, the newly-formed Massachusetts Provincial Congress was essentially a shadow government for all the Massachusetts towns outside Boston, citing the “intolerable grievances and oppression to which the people are subjected…manifestly designed to abridge this people of their rights…and, if carried into execution, will reduce them to a state of slavery.”

Patriot warnings that British policies would make slaves of all Americans did not go unnoticed among free and enslaved African Americans throughout the colonies. Indentured servants, apprentices, and enslaved people (sometimes referred to as “servants for life”) were common sights in fields, shops, and houses throughout British North America. By the mid-18th century, over a third of households on Deerfield’s mile-long main street included at least one enslaved person. At a time when slavery was legal in every colony, including Massachusetts, many people of color seized upon the revolutionary language of natural rights to claim the liberties Patriots insisted were the birthright of all people. Among them was Cesar Sarter of Newburyport, Massachusetts. Enslaved for twenty years before gaining his freedom, Sarter reminded readers of the Essex Journal in 1774, “I need not point out the absurdity of your exertions for liberty, while you have slaves in your houses…one minute’s reflection is, methinks, sufficient for that purpose.”

The Provincial Congress urged the continued boycott of English manufactures and declared tea drinkers to be “enemies of the country.” Predictably, the Reverend Ashley promptly held a tea party. Meanwhile, his son Elihu was starting his first medical practice in Worthington, Massachusetts, trying hard to establish a reputation as a skilled and trustworthy physician. Elihu was determined to keep his political opinions to himself but it was not easy. The month after he arrived, Elihu heard that the Worthington town meeting “was very much divided, and as it was upon Political Matters they could not agree. There was an Article in the Warrant to see if the Town would accept and put in Excon [effect] the Resolves of the Provincial Congress, there was Eleven that protested not to pay any regard to them, especially the Resolve respecting the Tea.”

Elihu played it safe, refusing to take tea except with members of his own family or among those with confirmed Loyalist sympathies. He tried to distance himself from those less discrete about their Loyalist opinions. Nathaniel Dickinson of Deerfield came to Worthington and heatedly condemned attacks on Loyalists “tho before this I advised him to be still and not say anything before the People, but he would not hold his Tongue and was too warm for his Interest.” Elihu’s words proved prophetic. Dickinson would flee to Halifax, Nova Scotia, during the war and his estate seized and auctioned off.

Relations between community members went from bad to worse. Elijah Williams had died in 1771, but his son John was just as much a Loyalist and not afraid to speak out. According to George Sheldon’s History of Deerfield, a mob gathered at Williams’s home but there were already a number of his friends inside, armed and ready for trouble. When the mob advanced to break down the front door an upstairs window opened and Major Seth Catlin appeared, musket in hand. He promised to blow a lane right through the visitors if they came one step closer. A committee was permitted to enter to discuss matters and apparently shared a deal of hot, strong flip. They announced when they came out that Mr. Williams was a good patriot and had given Christian satisfaction.

The business accounts of John Partridge Bull, a Deerfield gunsmith and blacksmith, attested to the rising tension. Bull repaired 36 guns in 1773, substantially more than the 16 he had worked on in 1771. The numbers would climb still higher over the next two years. From 1774 – 1775, Bull would repair a total of 159 guns.

Militiamen began drilling in earnest in towns throughout the Commonwealth. In places where Loyalist militia officers refused to participate, the men demanded and elected a new slate of officers. Meanwhile, the Reverend Ashley would not give in to community pressure from Deerfield’s Whigs. He refused to read from the meetinghouse pulpit the proclamation the Provincial Congress issued for a fast day in December 1774. When his son Jonathan acquiesced and read “God save the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, his father rose and added “And the King, too, I say, or we are an undone people.”

For the next five years, until his death in 1780, Deerfield split over what to do about their outspoken Loyalist minister. To Ashley, it must have seemed that the world of deference and hierarchy that had once made him the most respected man in the community had turned upside down. Those who supported him managed (barely) to keep the town from voting him out, but his salary remained in arrears and the town withheld his contracted allotment of firewood.

1775

By early April, 1775, the political situation in Worthington, Massachusetts, had become so tense that Elihu despaired of being able to stay there. On April 13, he wrote plaintively to his fiancé Polly Williams, “my God Who can take any comfort now a Days? I expect to be drove off fm Worthington before long. They begin to be very Inquisitive respecting Political Affairs and my Principles.” When news arrived in early April that more British Regulars had arrived in Boston, Deerfield Loyalists gathered to celebrate. Surely now, they reasoned, law and order would be restored and mobs would become a thing of the past. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. News of the fighting at Lexington and Concord reached Deerfield on April 20. Fifty Deerfield Minutemen quickly assembled and set off for Boston. Blood had been shed and there would be no turning back. The American Revolution had begun.