People in New England were driven by their Protestantism to become literate to enable them to read the Bible and they prided themselves on their ability to master the printed word. Between the middle of the 17th century and the end of the 18th, New Englanders evolved from a society with approximately half the population being literate to nearly universal male literacy. Women were often lacking in the skill of writing, but it is believed that most could read as well as the men they lived and worked beside.

Schoolmasters were hired almost as soon as ministers were in the early towns. The town meeting records of Deerfield, Massachusetts, reveal the first formal school was set up in 1698, only 16 years after resettlement in 1682. Before then there were undoubtedly “dame” schools, or primary schools run by women in their own homes; the dame schools continued for very young scholars even after the construction of school buildings for public education.

A schoolmaster was hired in 1702/03 in Deerfield, but by 1707, the schoolhouse had been sold because of the devastating attack on the town by French and their Native American allies in 1704. As a result, surviving families had evacuated to towns to the south. (The town remained occupied by 24 soldiers posted there to defend the town from any further attacks, and to provide a buffer to Hatfield to the south.) There is little mention of schools or schooling between 1707 and 1720, when the town was reeling from the damage done in 1704.

By 1760, the town fathers had voted to build a new schoolhouse of 22 feet square “doubly boarded on the outside ye wall filled in and light ceiled and double floored below.” The old schoolhouse was moved and converted to a ferry house at the north end of Pine Hill. We know that both reading and writing were taught since it is recorded that reading scholars paid two and one-half pence per week and those who wanted to learn to write paid one and one-half pence. Among the general population, more men and women knew how to read than to write. They wrote in cursive form, rather than printing as we often do today. Therefore, if one were not taught to write, it was difficult to read “written hand” in a letter, for example.

The years immediately after the American Revolution witnessed a great expansion of educational opportunity, a well-educated citizenry being necessary for the success of the republican experiment. Listing reading, writing, measurement and arithmetic, geography, and history as the subjects that ought to be taught in primary schools, Thomas Jefferson said the purpose of these institutions was to “instruct the mass of our citizens in these their rights, interests, and duties, as men and citizens.”1

Interest in formal education was also encouraged by the credit economy that was in place. Farmers and artisans conducted their business with little exchange of actual money. Credit was the rule, but there was no formal institution to regulate the exchange or to articulate the rules. Instead, the barter system was in place which required, in addition to faith and trust in one’s neighbors, a well-developed system of record keeping. Debts were computed in terms of monetary equivalents according to the prevailing standards of value, and then were recorded as so many pound, shillings, and pence owed. Literacy was the avenue to careful record keeping, which, in turn, could mean the difference between survival and the collapse of a trade or a business.

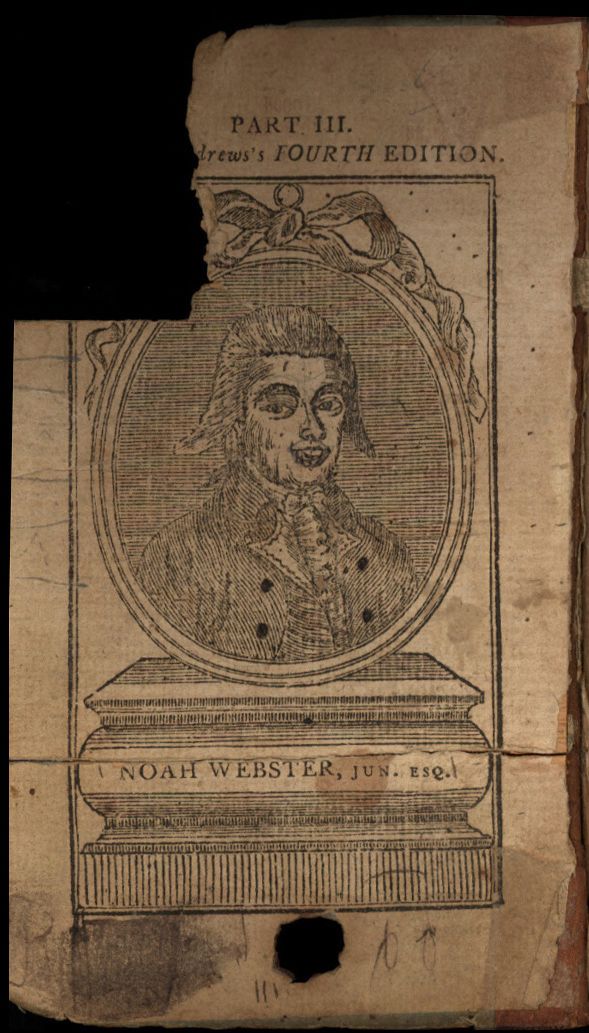

By 1787, Deerfield, Massachusetts, was divided into six school districts with an amount of money assigned to each and in the next year a schoolhouse was built near the center of town. This was a public school, but plans were already being readied for the formation of a private academy. The charter for Deerfield Academy was drawn in 1796, and construction of a two-story brick building began the next year. The school opened on January 1, 1799. At that time, no academies existed to the west; one had been chartered in New Salem to the east, but the 12 others in Massachusetts were all 100 miles or more from Deerfield, along the eastern coast.

The Academy provided limited boarding for students only after 1811, so those pupils whose homes were beyond commuting distance lodged with Deerfield families. Not only had the substantial brick academy building changed the landscape of Deerfield, but the composition of the town was forever changed by the addition of students from different backgrounds and environments with new ideas and varied perspectives.

Deerfield Academy was established for “the promotion of piety, religion, and morality, and for the education of youth in the liberal arts and sciences, and for all other useful learning.” All were instructed in reading, writing, and English grammar. Because of the Academy, Deerfield was now catapulted into the role of a center of learning. The school caught the attention of all of New England, especially when it was learned that of the 49 scholars admitted in the winter term of 1799, eight were female. The practice of admitting female students was not standard in the existing academies, but a number of leaders believed that the education of young ladies was considered important so that “not only the Fathers, but the future Mothers of our race, may be richly furnished to train up their children to learning and virtue…”2

As Linda Kerber has stated in Women of the Republic, literacy is more than a technical skill. It opens one up to the larger world and makes possible certain kinds of competencies. In addition it makes practical the maintenance of a communication network wider than one’s own locality, which then allows for access to viewpoints to add to those accepted in the immediate community.

Endnotes

1Quoted in Fred M. and Grace Hechinger, Growing up in America (New York, 1975), 41.

2Reverend Joseph Lyman, A Sermon delivered at the opening of Deerfield Academy, January 1799 (Greenfield, MA, 1799), 14.