by Susan McGowan

“People “in the know” command powers that the ignorant lack,” a thought taken from Francis Bacon, 1597. And from Samuel Johnson, c.1770, “society is held together by communication and information.”

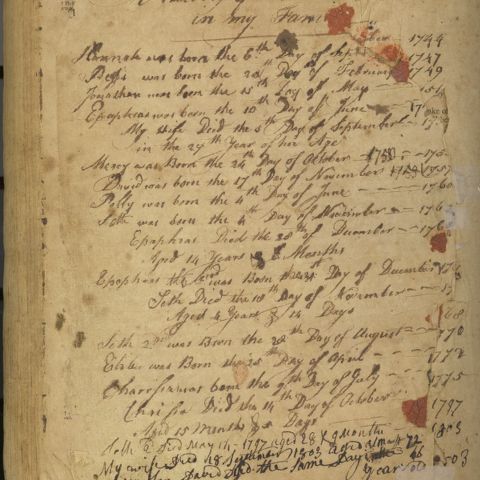

The transformation of society, from colonial to national, was a cumulative phenomenon. The population of the country in 1700 was 250,000, but by 1865 it was 36 million. Colonial society was a face-to-face culture in a time of relative scarcity of information with limited topical range. Most New Englanders were literate, driven by their Protestantism to read the Bible, but the majority of people at that time conversed, read, and attended public gatherings to satisfy personal needs and to express their sociable natures or to feed their spirituality by weekly church attendance. Word of mouth and personal correspondence were the major means of gathering information.

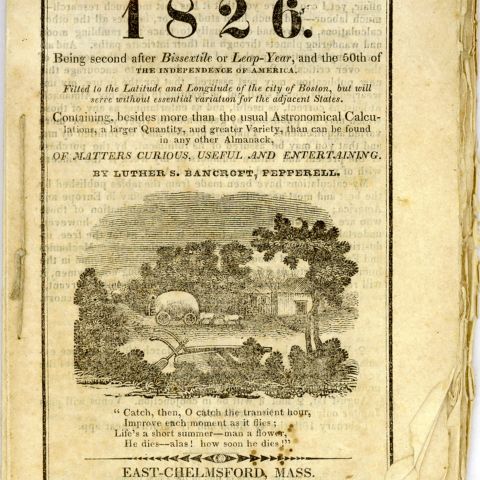

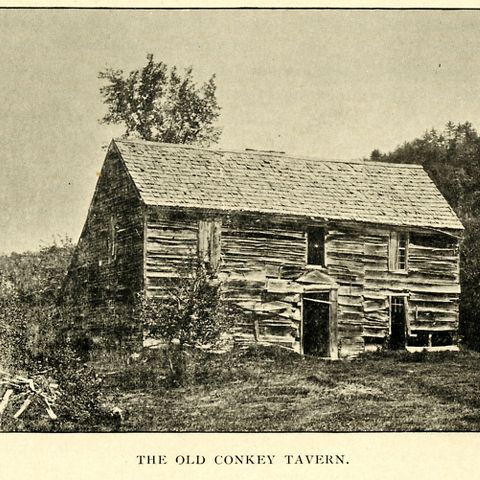

The rank or social stature of persons determined who would be the purveyors of information; those in power talked mainly to each other and were the ones who then made the decisions. Common folk spent their days at labor and joined in conversation with family members and neighbors of similar backgrounds. The rural poor, white or black, had little time or occasion for reading, except for the Bible and perhaps an almanac. Visits to the local tavern might bring news of a more global nature, if it were a place also frequented by travelers or tradesmen.

Even though diversified, colonial society was essentially a collection of local societies in which a coherent Christian culture was perpetuated. Both reading and oratory were dominated by religious messages; the themes of order and stability that were expressed by church and state were mutually subordinate to cooperation in both community and commercial life. As the nineteenth-century republic developed, competition began to replace coherence in public life.

Clergymen and politicians who could win the largest audiences, lyceum speakers who could sell the most tickets, authors whose works sold most widely became influential not because of any office they held or any prescribed public role, but because of their engaging public performances. In a competitive environment of regional or national dimensions, where purveyors of each type of information had to compete with others conveying similar information as well as with a multitude of entirely different sorts of information, each individual was invited to his or her own coherent culture from within the galaxy of religious sects, political parties, and reform societies that were thriving in the new republic.1

The change probably began in the Great Awakening of the 1730s with the notion of individual choice forcefully asserted. It was furthered when the consumer revolution – later in the century – which brought printed textiles, fashionable furniture forms, and improved ceramics, also brought a wealth of information to the general public.

Face-to-face communication has never disappeared and remains crucial in the everyday experience, but when the diffusion of this burgeoning of public information moved from face-to-face networks to the newspaper page, profound public influences began to replace communal ones. Face-to-face communication is personal and governed by the relationship of the speaker to the listener. Print required no such inhibitions. The speaker, to be sure, was still subject to some restraints as a writer, but the listener/reader could react privately and, therefore, more freely. He could growl, frown, or ignore the text altogether. Newspapers opted to become neutral and non-partisan with the information they printed or to become frankly partisan. In either case, once the newspaper became cheap and abundant people expressed their own individuality by choosing to read or to ignore the information contained in them. The production and distribution of newspapers, periodicals, and books – small-scale in the colonial era and reliant chiefly on imports – became big business. By 1850, 22,000 men, plus a lesser number of women and children, were printing and binding billions of items annually, plus producing ink, paper, and the type necessary to support the system. Diffusing information became a great national enterprise and “parochial ignorance was no longer legitimate.”2

Nineteenth-century American society was now characterized by the movement of public information from distant, impersonal sources direct to individuals, independent of family, neighborhood or any face-to-face connections. Aided by the republican belief in a social hierarchy based on achievement rather than heredity, the information explosion marched on; the acquisition of extensive knowledge was prescribed for republican citizens in all walks of life. The widespread aspirations of gentility, which took place at the time of the American Revolution, made it increasingly attractive from a commercial standpoint to introduce books, periodicals, newspapers, and public speech to a vast audience of common people.

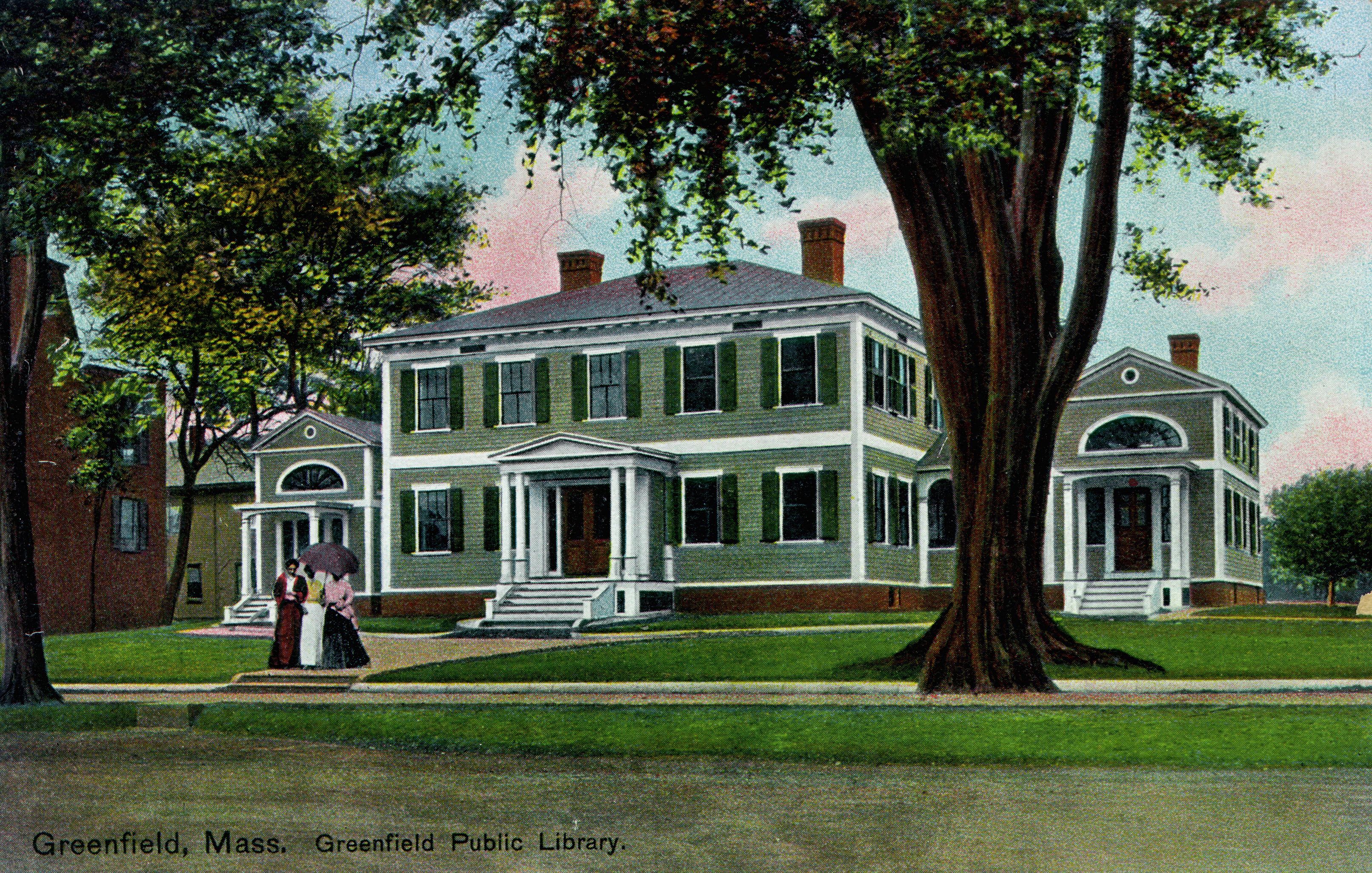

By the mid-nineteenth century this proliferation of printed matter was available to all citizens through public and private library societies, clubs, lyceum lectures, newspapers, and book stores which featured fiction, reference works, legal, medical, and religious texts, as well as practical manuals and the continuously-present Bibles and almanacs.

Endnotes

1Brown, Richard D., Knowledge is Power, The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, 296.

2Brown, Richard D., Knowledge is Power, The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, 290.