by Susan Titus

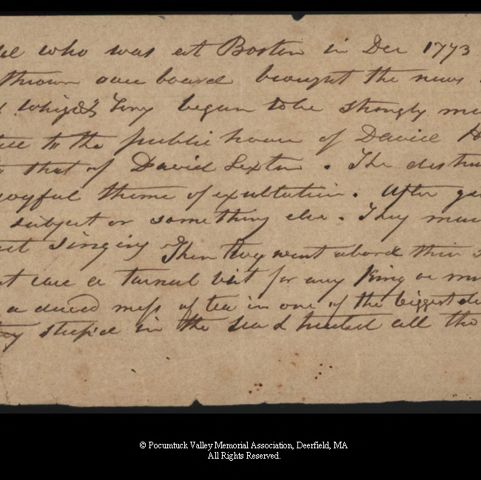

When New Englanders speak historically about TEA, probably nine out of ten of them remember the Boston tea party of December 1773. Although Deerfield, Massachusetts, is one hundred miles west of Boston — a three-day ride on horseback – news of the “big dish of tea brewed in Boston Harbor” traveled to that Connecticut Valley town as quickly as David Field, who was in Boston that night could urge his horse to his home in Deerfield. His news was met with jubilation by fellow Whigs and it was reported that they convened at David Saxton’s tavern near the common for a “jollification” meeting the evening Field arrived. You may be sure that stronger drink than tea was served that night!

Considered an exotic beverage when it first made its way onto the tables of the wealthiest Europeans and American colonials, tea was valued in the west as a “very expensive medicine.” Believed to cure the respiratory ailments, headaches, giddiness, heaviness, colds, and dropsy, tea was reputed to be a restorative against the loss of body fluids caused by excessive sweating and purging, two common medical curatives of the day.

Another exotic drink, CHOCOLATE was supposed to arouse people’s passions and it was said that chocolate could turn old women young and fresh. It was promoted as a mood enhancer and, in addition, as a positive cure for any kind of stomachache. And COFFEE, the third of the brews with almost magical properties, then as now touted as a beverage that made people wakeful and alert. All three beverages began to gain popularity in Europe around 1650 when they were introduced by traders from Holland, Portugal, and England. Coffee was the first of the three luxury drinks to become affordable to the masses. Colonial Americans had coffee houses in cities like Boston by the late 17th century, but tea and chocolate arrived a little later. Until the late 1800’s, all TEA came from China because that country had the right climate and the large labor force necessary for harvesting the camellia sinensis. The tea plant is really a shrub, first cultivated in China, but later introduced to Japan, Sri Lanka, and other countries by monks and European traders.

Tea’s domestic success was ensured in England with the marriage of King Charles II to the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza in 1662. Catherine was already familiar with tea and the ritual of its preparation and when she arrived, she encouraged the drinking of tea at court. On a more modest level, we find a reference to tea in the diary of Englishmen Samuel Pepys who recorded on June 28, 1667, “By coach home and found my wife making tea; a drink Mr. Pelling the apothecary tells her is good for cold and defluxions.” In 1717, also in London, Thomas Twining (whose name is still famous for tea products) opened the first tea shop for ladies.

Tea was the first safe non-alcoholic drink and despite the high cost of the tea leaf, the tea drinking habit gained momentum. In the 17th and 18th centuries it was customary for most people, and that included children, to drink cider, wine, and ale daily since unboiled water supplies were not safe and milk was considered only for babies and very young animals.

Along with tea came another import — porcelain. TEA requires that boiling water be added to the tea leaves which are then brewed or steeped, for several minutes. The European earthen ware of the day wasn’t strong enough to withstand the boiling water and often resulted in thermal shock which cracked the tea cup or pot. One reason for pouring milk or cream into the teacup before adding the tea was to buffer the weaker ceramics against the sudden heat of the brew. Chinese porcelain, fired at temperatures of 1400 degrees, was strong enough to sustain the thermal shock and the wares began to be imported into Europe and England and, eventually, America. It was nearly one hundred years before the first European porcelain was perfected in Meissen, Saxony (Germany) in 1710. Later France would discover the formula and even later England would begin manufacture. The English potters had experimented with the making of porcelain throughout the 18th century, but failed to understand that the product is achieved through a merging of two different clays — petuntse and kaolin — one the “bones” and the other “flesh.”

In the 1770s and 1780s it became fashionable to drink tea from the saucer, perhaps to allow the tea to cool. One consistent characteristic of tea wares at that time was the deep saucer, borrowed from China. Later in the century, cup plates became part of the tea set and allowed the tea drinker to “park” her cup on the small cup plate while she sipped tea from the saucer — all this in a seated position instead of standing, as before.

Often kept in locked cabinets or small wooden boxes called tea caddies, fresh tea was brewed in the morning. It was then not unusual for the tea leaves to be strained and reused for tea in the afternoon. Tea sets often included a tea bottle, a small lidded flask-like vessel, which held a modest supply of dry tea leaves. Because of the expense of tea, it was considered just as rude for the guest to refuse more as for the hostess not to refill one’s empty cup. Generosity and acceptance were the fashion so, in America, guests learned they must turn their teacups upside down when they had enough.

By the 1840’s, when the evening meal had advanced to 7:30 or 8:00 in fashionable homes, the gap between it and the noonday meal became uncomfortably long. Among the causes for the delay were longer journeys home from the office to outlying districts, longer office hours sometimes followed by visits to gentlemen’s clubs, and the invention of gas lighting, which extended the work day. Ladies began to take a meal of tea and cakes in the afternoon, at first in the bedrooms and then in a downstairs room. By 1850, in England, tea at this time of day had become customary in most middle-and upper-class homes.

Although most men reportedly thought that the hour was devoted to the ceremony known as afternoon tea was “a mild form of dissipation’, the ladies were said to have enjoyed it immensely. The usual ratio of men to women at these afternoon gatherings was said to be five to thirty.

Hostesses tried to outdo each other with a display of their finest china services, table linens, and cake stands, accompanied by an array of small cakes, biscuits, and at least one large cake — either fruit, caraway, or Madeira — as well as hot teacakes and thin sandwiches. (“The slices of bread which you serve with your tea,” wrote Pastor Miritz in 1782, “are as thin as poppy leaves.”) Ladies had to remove their gloves to eat ices, fruit, and sandwiches, but their hats remained firmly on their heads.

By the second half of the 19th century, afternoon tea was being adopted by lower-class homes. A “family” or “high” tea could consist of crusty bread and butter, muffins, and crumpets, cheese, potted spreads of meat and fish, as well as various kinds of cakes. A “small” tea was likely to be composed of thin bread and butter, jam or honey, and cake.

As more women began to work outside the home, teashops were introduced where they could comfortably meet and not be classed as prostitutes, as had been the case in former times.

Encouraged by the temperance societies during the 19th century, tea drinking increased dramatically. Until then, tea had been imported only from China and at considerable cost, but with the discovery of tea growing wild in Assam by Sir Bruce in 1826, a committee was set up in England to plan its cultivation in India on a large scale. The new varieties of tea were soon available in abundance and the prices tumbled. As a result, by the 1840’s, tea was being drunk by all working people and it often comprised the only hot item in their diets. A quite deceptive feeling of warmth and satisfaction can be enjoyed after a pot of tea, although it truly has minimal food value. In reality a glass of cold beer makes a more substantial contribution to one’s nutrition.

Between 1840 and 1890, the consumption of tea in England rose from 1.6 pounds of tea per person annually to 5.7 pounds (about four cups daily), taken at breakfast, at work at the noon day meal, with supper, and at social gatherings. Everyone was drinking tea, and if you have been to England recently, they still are. To further illustrate its popularity, consider the example of British statesman William Gladstone (1819-1889), who was so fond of the beverage that he was reputed to have put tea into his hot water bottle in order to have a supply ready during the night.