This exhibit was developed to explore the five themes below across three “turns” of the centuries: 1680–1720, 1780–1820 and 1880–1920.

First Turn: 1680 – 1720

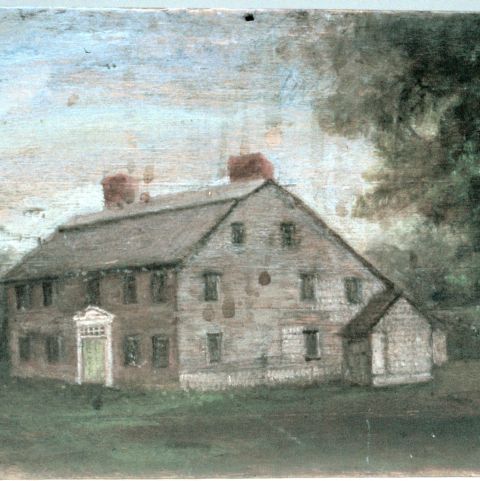

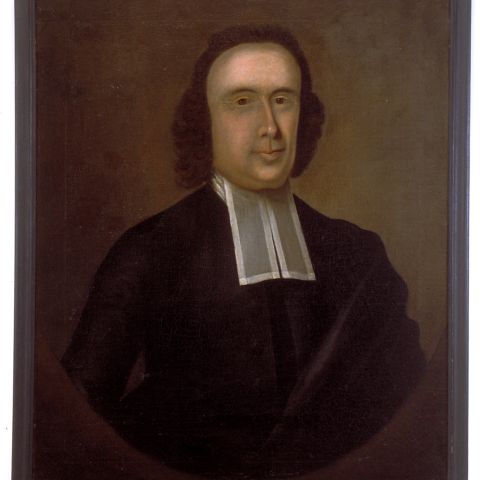

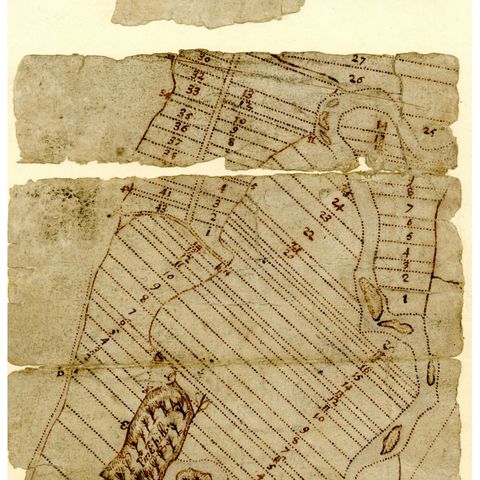

The Spanish, Portuguese and French dominated early exploration and trade in North and South America. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, the English colonies had more than made up for lost time. Their success in attracting settlers was unmatched. From the earliest period of colonization at the turn of the seventeenth century until 1760, as many as 700,000 British men, women and children left the Old World for the New. Social, economic and political developments in the seventeenth century lay behind this unprecedented movement. High rents, periodic food shortages, civil war, and diminishing opportunities pushed some people toward the colonies, while dreams of prosperity drew others. Persecution or the fear of persecution for religious or political reasons induced still others to leave their homeland. And, by 1619, the first involuntary African immigrants arrived in the colonies and were present in the Massachusetts Bay Colony by 1638. Developing from frontier outposts into thriving provinces was not without growing pains. Religious disputes, economic crises, and political unrest characterized colonial life at the end of the eighteenth century. Much of this tension grew out of the colonial experience itself. Most people believed, like the New England minister Jonathan Edwards, that every person had an “Appointed office, place and station, according to their several capacities and talents, and everyone keeps his place, and continues in his proper business.” In reality, the colonies could not recreate the elaborate hierarchy of wealth and status that structured English society. Through it all, successive waves of newcomers continued to play a critical role in creating, defining and redefining colonial society.

Second Turn: 1780 – 1820

In 1780, about three and a half million Americans lived in the area east of the Mississippi River. By 1820, the population had swelled to nearly ten million people, many of them surging westward in unprecedented numbers. Beckoned by seemingly boundless opportunities and fertile land, Americans at the turn of the nineteenth century were, above all, a restless people. Europeans used to seeing men and women live for generations in the same village witnessed with amazement a nation on the move. Before the American Revolution, Americans had looked to Western Europe for models of genteel behavior and civilization. In the decades following the war, Americans acted upon what they felt had been the promises of the Revolution. In so doing, they rejected forever the hierarchical, patriarchal society of the eighteenth century. In its place rose new, voluntary forms of association. Americans, observed the French traveler Alexis de Tocqueville, “are forever forming associations…of a thousand different types …Americans combine to give fetes, found seminaries, build churches, distribute books, and send missionaries”. Foreign observers remarked with amazement on America’s leveling spirit, the democratic impulses that swept away old customs and usages for the new belief that one white man was as good as another, regardless of his birth. Inequalities of wealth abounded but what mattered most to Americans in this period was the perception that all men could succeed on their own merit. Voting requirements based on property and other measures of wealth fell by the wayside as the right to vote expanded to include virtually all white males. This radical vision of equality was for the most part confined to white men, however. Blacks, Native Americans, women and many other Americans in this period continued to suffer under political exclusion and economic exploitation and in some cases lost suffrage and other rights of citizenship. At the same time, some abolitionists and utopian dreamers of the antebellum period and beyond insisted upon equality of opportunity for all Americans, regardless of economic status, race or gender.

Third Turn: 1880 – 1920

In 1800, the United States was a fledgling nation embarking on a brand-new experiment in republican government. Seventeen states hugged the eastern seaboard as explorers and settlers established territories in the west. A mere handful of manufactories in New England experimented with new machines and methods for textile production. The vast majority of people lived and worked on farms. The total population was less than six million. One hundred years later, seventy-six million people lived in the United States. The country spanned the continent and railroads linked the East and West Coasts. Almost half of all Americans living in the Northeast dwelt and worked in cities of more than 8,000 people. The same would be true for the nation by 1920. Millions of Americans migrated west or to urban centers. Hundreds of thousands of African Americans migrated to northern cities. Thousands of Native Americans experienced forced migration and relocation. Always a nation of immigrants, the United States experienced unprecedented immigration in this period. These newcomers flooded into cities and rural communities. They struggled to adapt to a new country while preserving their own distinct cultures, languages, and belief systems. Rapid advances in technology and industrialization changed and continued to change the way in which Americans lived and worked. Mass manufacturing made available cloth and ready-made clothing to consumers. Electric lighting and running water became more common, especially in urban areas. These developments had a darker side, however. Men, women and children worked long hours in unsafe factories to meet the insatiable American appetite for cheap, mass-produced goods. Jacob Riis shocked viewers with his photographs of the living conditions among the urban poor. Lincoln Steffens’ exposé on the political corruption in the nations’ cities scandalized the country. Meanwhile, rural farmers struggled to keep their farms in the face of increased competition, costly machinery, and falling prices. The failure of post-Civil War Reconstruction to secure the rights and liberties of African Americans bore bitter fruit, especially in the southern states. The social and economic stresses that accompanied rapid industrialization took its toll on Americans in this period. American culture promoted the family circle as a haven from the pressures of urban and industrial life. Parents were urged to protect the innocence of their children from the harsh reality of the outside world for as long as possible. Men and women struggled with newly emerging gender roles and responsibilities as more and more women entered the work force through choice or necessity. Many Americans looked back with nostalgia to the country’s pre-industrial past even as they celebrated the accomplishments of the twentieth century.