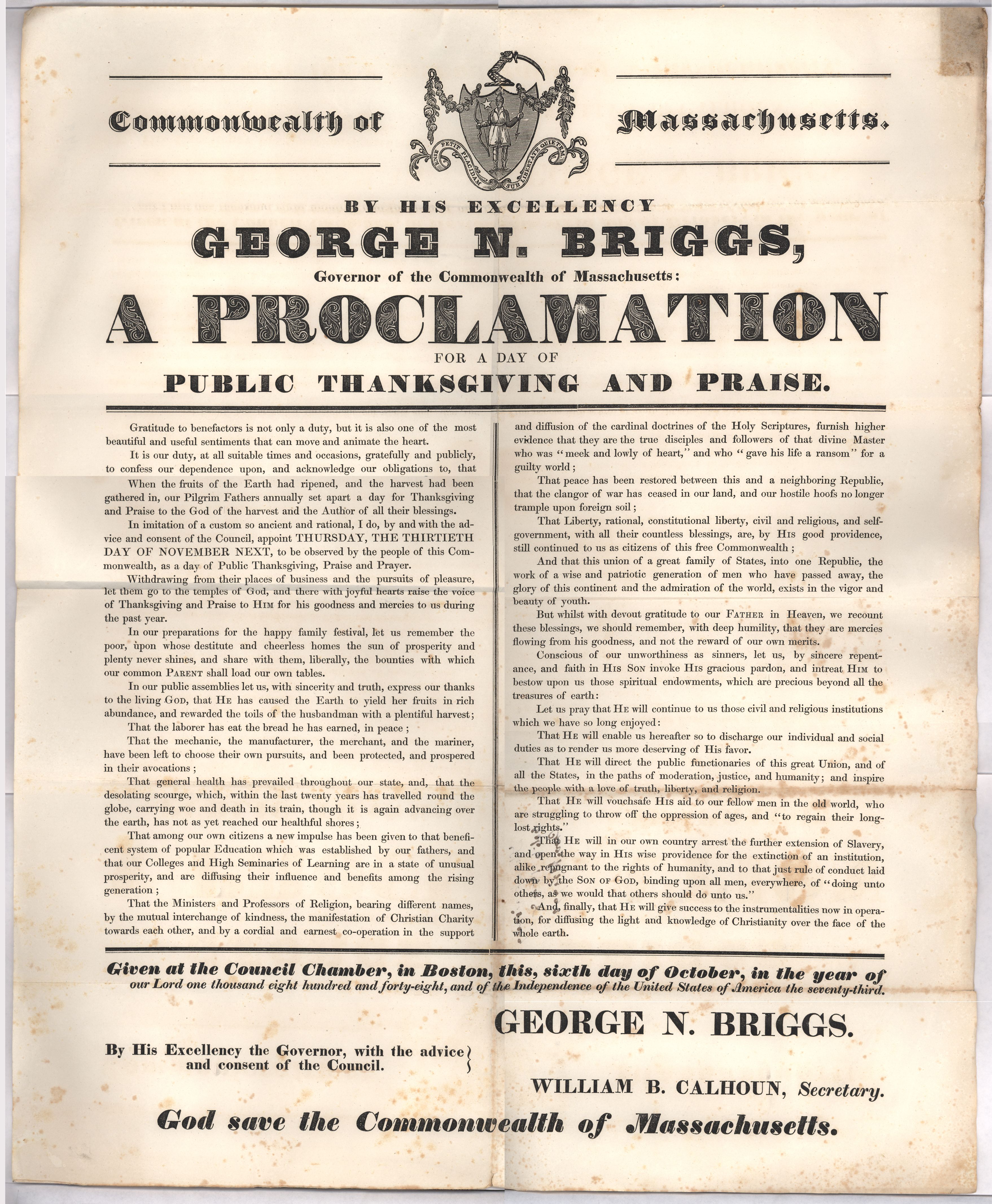

The Mexican War had its roots in land issues between the United States and Mexico. By the 1830s, Mexico’s claim to a good portion of the American Southwest was several hundred years old. Settlers of Spanish descent occupied the rich lands of California, New Mexico, and Texas, but only lightly; large areas remained entirely occupied by Native peoples. Texas was Mexico’s closest province to the United States, a large tract largely populated by Native Americans. In 1821 Mexico had gained its independence from Spain and wanted to populate Texas with non-Native Americans, but few Mexicans wanted to move that far north to a hostile land. Mexico then encouraged Americans to settle Texas and several thousand settlers came. With Texas being so near the southeastern U.S., most of the settlers were slave owners, and they quickly established large cotton plantations. In the decade and a half after its independence Mexico was politically unstable, and Texans were allowed near-autonomy. By the mid-1830s, Mexico had created a stronger central government under General Santa Anna, and the Texans worried they would be drawn under Mexican authority and perhaps even lose their slaves. They went into open revolt in 1836 and after their victory at San Jacinto they forced Santa Anna to sign a treaty recognizing the Republic of Texas. Texas then petitioned the U.S. Congress to be admitted as a new state, but antislavery activists blocked the bill. In 1844, James K. Polk won the U.S. presidency, having run on a pledge to annex the entire west for the United States, based on the concept of “Manifest Destiny.” The U.S. election of 1844 also produced a bare majority in the Senate favorable to making Texas a state, and it became a state the next year. Polk then sent an army into the disputed region. The Mexicans crossed the Rio Grande and on May 13, 1846 Congress declared war. The war was highly unpopular in New England in particular, which saw it as an attempt by slaveholders to expand the number of slave states. The war was extremely popular in the South, especially in the newer states, which saw the potential for an increased number of slave states carved from captured Mexican territory. In early 1847 U.S. General Zachary Taylor defeated the main army led by Mexican President (and General) Santa Anna at Buena Vista. At that point, it appeared the war was over, but President Polk detested Taylor and wanted to squelch his chances of a successful run for the presidency. Polk adopted the plan that General Winfield Scott had drawn up for a march on the Mexican capitol from the port of Vera Cruz. The march was dramatic and highly successful, and after the battle of Chapultepec, Mexico City surrendered (September 17, 1847), Santa Anna resigned, and the war was effectively over. The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February 1848 ceded all the land Polk had sought. In all, more than half of Mexico was taken, although the U.S. made a relatively small financial settlement in compensation for it. The ceded territory would become the fantastically rich states of the American West, but the immediate aftermath was to increase divisions between free and slave states. Evidence of mounting tensions over the issue could be seen in expressions such as the October 6, 1848 Thanksgiving Day proclamation by Massachusetts Governor George N. Briggs, which included a call for an end to “the further expansion of slavery.” Debate over the slave status of the territories gained in the Mexican War proved so divisive that it would be a key cause of the Civil War (1861-1865) a generation later.

Mexican War

Details

| Date | 1846–1848 |

| Event | Mexican War. 1846–1848 |