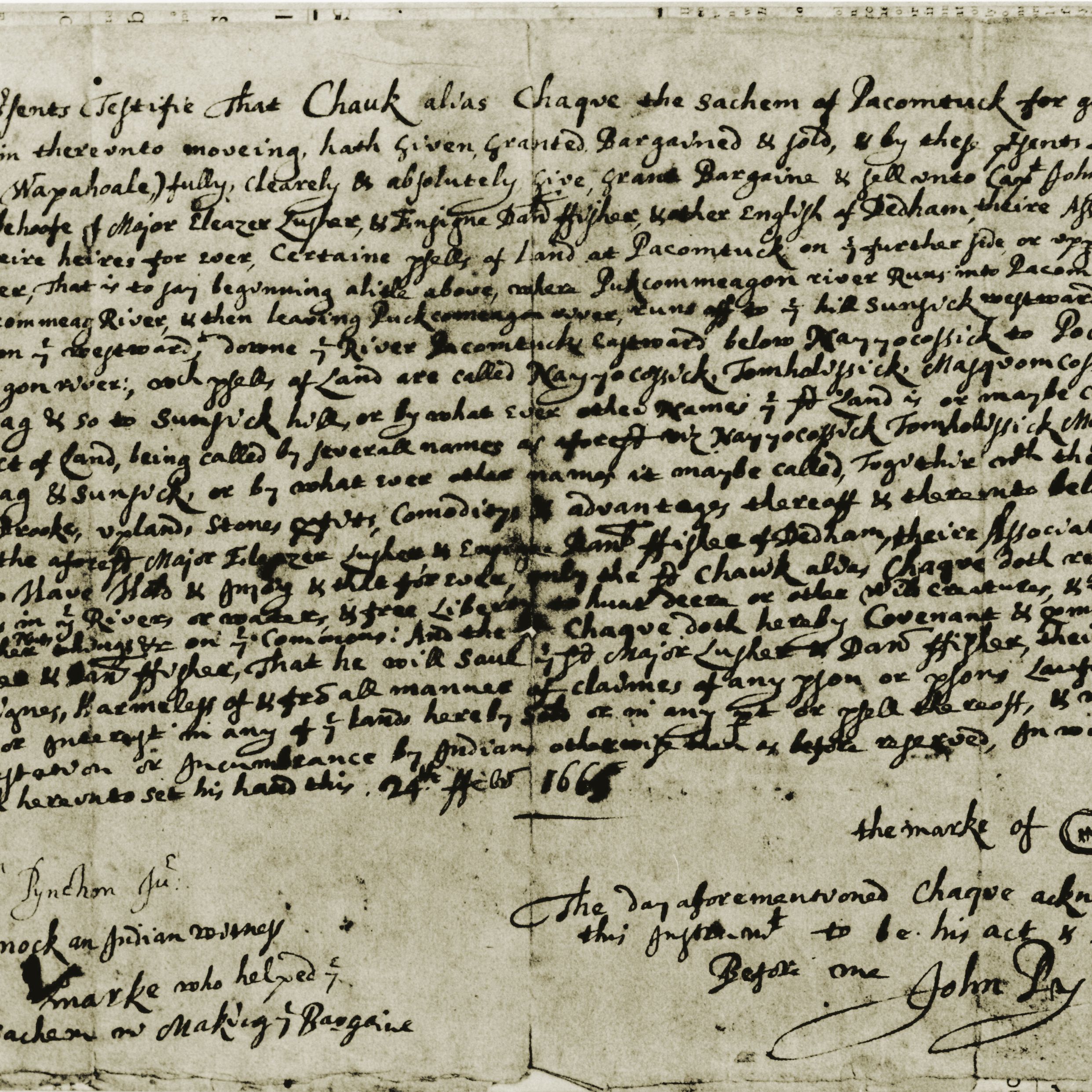

The Connecticut River Valley contains some of the richest agricultural lands in the northeast. It has been a vital crossroads for Native peoples for more than 10,000 years. European explorers and settlers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries encountered an indigenous people who had developed intricate spiritual relationships with the land and all other living beings in their environment. Agrarian rhythms defined the newly-arrived colonists’ relationships with the land. Agricultural practices such as a common field system reflected the essentially communal culture of western Europe in the 1600s and early 1700s, as did the way in which people lived in and used their homes.

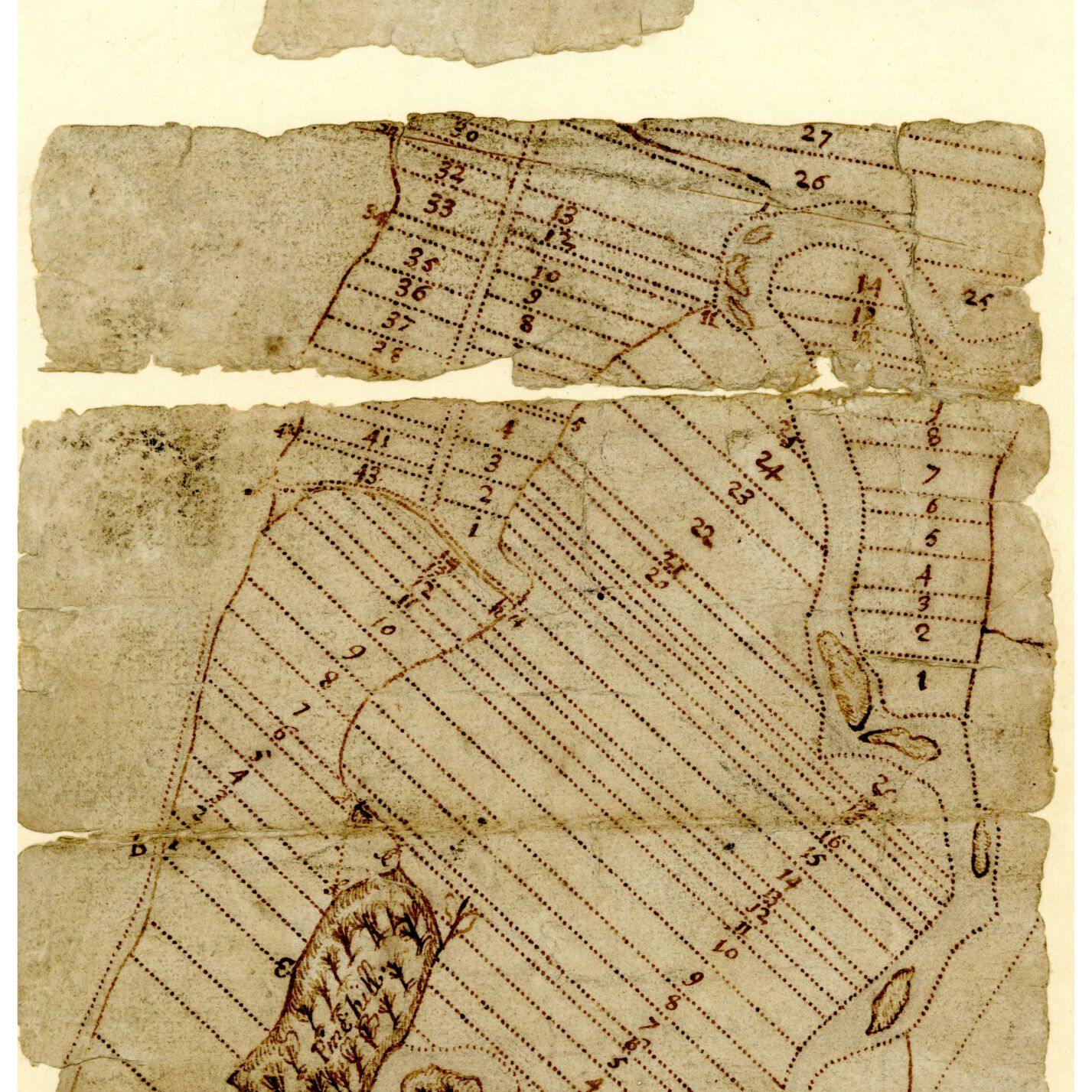

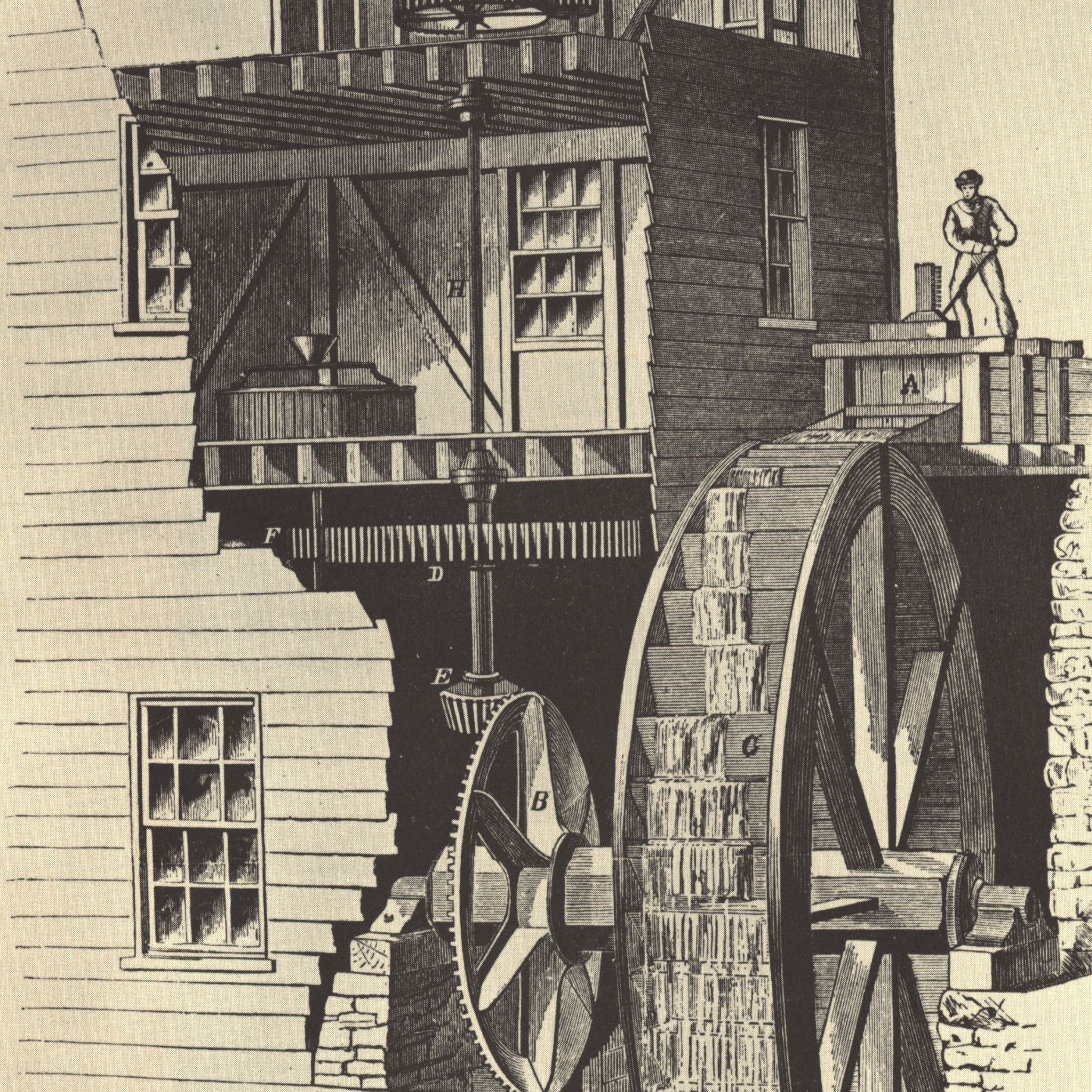

Most early European settlers viewed the North American landscape as a vacant wilderness to be possessed, planted, and subdued. Most New England towns took care to make sure that town founders, called proprietors, received land suitable for tillage, pasture and wood harvesting. Flour mills and sawmills were among the earliest and most important industries in colonial settlements. The Puritans who founded many New England towns intended their communities to be models of Christian love and good government. The meetinghouse was the center of public and religious life.