This November 1951 photograph shows Nevada troops watching a U.S. nuclear field test from six miles beyond the detonation site.

In a televised address on July 26, 1963, President Kennedy informed the nation about the country’s participation in the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

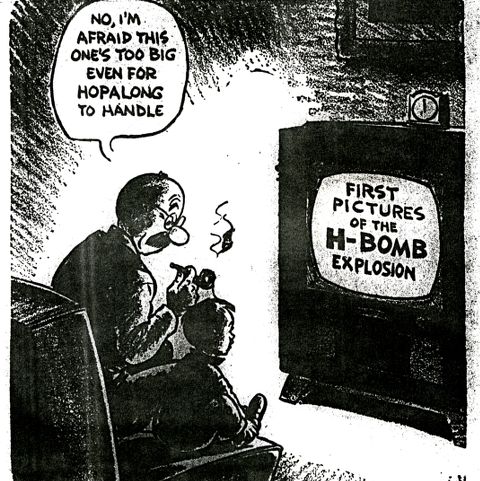

With the United States’ detonation of the world’s first nuclear weapons over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in August of 1945, the Second World War ended. As the Cold War between the Communist countries of the East and the Democratic countries of the West commenced, the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union developed and tested ever more powerful nuclear weapons. The First World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held during August of 1955 in Hiroshima, a little over a year after the test of an American hydrogen bomb rained deadly nuclear fallout onto a Japanese fishing vessel. Less than a year after the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, at which time the United States and the Soviet Union narrowly averted a nuclear war, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States signed the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water. For a decade, Ray Elliott worked at a tracer laboratory where, he explains, “we had to monitor the radiation fallout around different parts of the world. They’d send us samples of air samples, vegetation…to our lab and we would break it down and count the radioactivity fallout, mainly to monitor…since there was a moratorium on the testing of atomic bombs after Hiroshima, mainly to determine whether other countries around the world were testing atomic bombs.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X converse as Dr. King leaves a press conference on March 26, 1964.

Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X embodied opposite approaches to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Advocating militancy, Malcolm X totally disagreed with Dr. King’s belief that nonviolent protest and civil disobedience would lead to black civil rights. Malcolm X once stated, “The only revolution in which the goal is loving your enemy is the Negro revolution. Revolution is bloody, revolution is hostile, revolution knows no compromise, revolution overturns and destroys everything that gets in its way.” Ray Elliott, who believed in peaceful resistance and became a youth advisor, training civil rights workers and organizing boycotts for the NAACP, relates how he confronted Malcolm X who was speaking at a Boston mosque.

Clouds of dark smoke rise from burning buildings during the August 1965 Watts Riots.

Despite the groundbreaking Civil Rights Act of 1964, Ray Elliott believed that there were “no real solutions in enforcement of legislations to be changing the hearts and minds of man.” Events bore out Ray’s concerns. In November 1964, 65% of California voters negated the Rumford Fair Housing Act (which had ended housing discrimination in the state). By amending the state constitution to bolster the rights of property owners, California’s Proposition 14 circumvented the Federal Civil Rights Act which had ended legal segregation a few months before. Further, urban riots, resulting in 34 deaths and over 1000 injuries, erupted in Los Angeles just five days after the passage of the Voting Rights Act which had ended legal voting discrimination. On August 17th, Martin Luther King, Jr. stated that the cause of this violence was “environmental and not racial. The economic deprivation, social isolation, inadequate housing, and general despair of thousands of Negros teeming in Northern and Western ghettos are the ready seeds which give birth to tragic expressions of violence.”1 Several days later, on August 20th, Lyndon Johnson stated in his “Remarks at the White House Conference on Equal Employment Opportunities”,

If there is one thing I think we have learned from the civil rights struggle, it is that the problem of bringing the Negro American into an equal role in our society is more complex, and is more urgent, and is much more critical than any of us have ever known. Who of you could have predicted 10 years ago, that in this last, sweltering, August week thousands upon thousands of disenfranchised Negro men and women would suddenly take part in self–government, and that thousands more in that same week would strike out in an unparalleled act of violence in this Nation?2Footnote 1. Martin Luther King Jr., Statement on riots in Watts, Calif., 17 August 1965, Southern Christian Leadership Conference Records, Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Inc., Atlanta, GA toURL=”http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/article/watts_rebellion_los_angeles_1965/”>Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles, 1965) (http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/article/watts_rebellion_los_angeles_1965/)

Footnote 2. Lyndon B. Johnson, toURL=”http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=27170″>Remarks at the White House Conference on Equal Employment Opportunities”, August 20, 1965. Accessed March 23, 2009. (http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=27170)