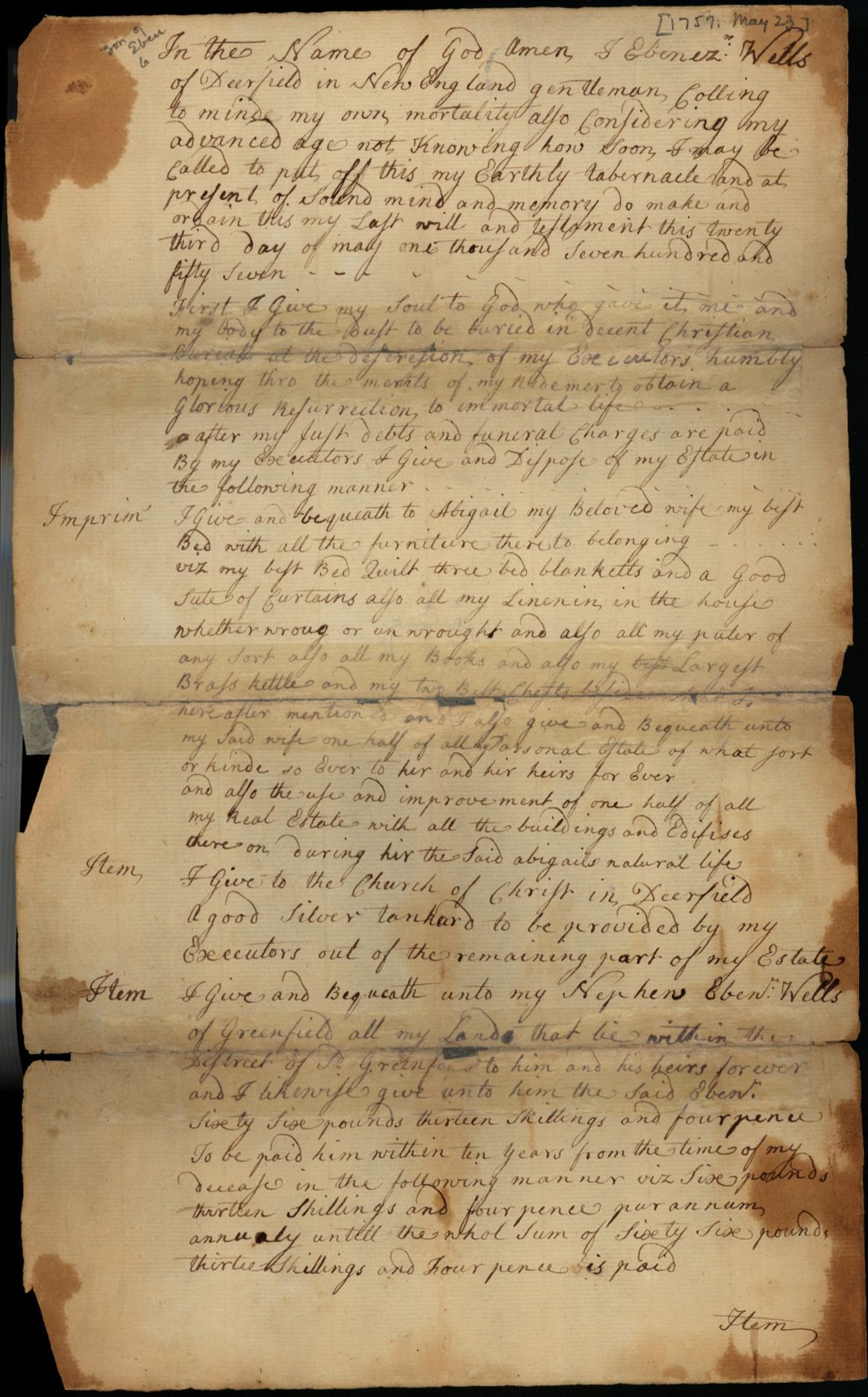

Ebenezer Wells, born in Deerfield, Massachusetts, September 13, 1691, was sixty-five years old on May 3, 1757, when he wrote, or dictated, his last will and testament. Mr. Wells died on June 12, 1758, a little more than thirteen months after the document was written.

Many New Englanders did write wills, but many did not. Those who died without a will were declared “intestate,” and the courts apportioned their worldly goods and property [estate]. This insured that the man’s debts were paid and that his wife and children received their just inheritances.

All wills in the eighteenth century have certain points in common – the writers leave their souls to God and declare the conditions of their burial, and they delineate their worldly goods to their heirs as they wish – but the documents are much more individual than wills written today. Later, in the nineteenth century, parts of legal documents were printed and only specific sections were written by hand. Today we speak of “boiler plate” documents and by that we mean uniformity – documents are printed in volume and one will or deed is structured exactly like another with only the names, the possessions, or property lines distinguishing one from another. In the period in which Ebenezer Wells lived, the mid-eighteenth century, each document was an individual one. The language of each is similar, but is particular to the individual in question.

For example, Mr. Wells first invokes the name of God and follows by naming himself a “gentleman” in New England. He states that he is of sound mind and memory but realizes he has reached an “advanced age” and does not know how soon he may be called from his earthly tabernacle.

After the above formalities, Mr. Wells then proceeds to “give and dispose of” his Estate. The expressions and some of the vocabulary may be unfamiliar to a modern reader, as will a number of the objects he “gives and bequeaths.” The handwriting is easily read, once the reader remembers that the medial “s” is ordinarily written as an “f,” and that capital letters may or may not occur where expected.

As is expected, Mr. Wells first names his wife, Abigail. By law, the widow receives her “thirds” of her husband’s estate whether or not a will has been written, but in a written will she may be given more than one-third, as occurs in this instance. Mr. Wells leaves to his wife one-half of all his personal estate plus the “use and improvement” of one-half of all his real estate. Women did not ordinarily inherit real estate as owners, but were instead given the use of the property so long as they did not re-marry.

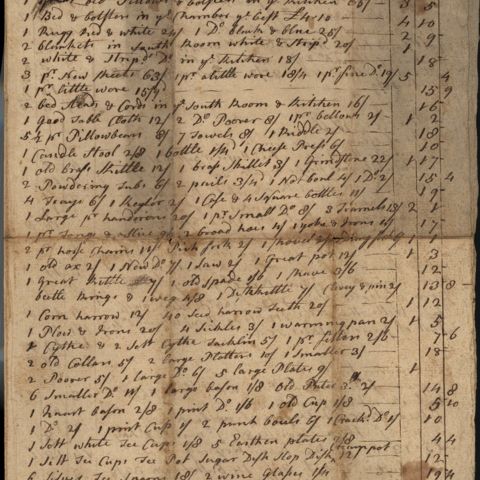

In his personal estate, Ebenezer leaves to Abigail his best bed “with all the furniture thereto belonging.” The best bed, with all its sheets, blankets, and bed curtains was very likely the most expensive item in the inventory of an 18th century family. Textiles, because of the time it took to process them from sheep’s wool or flax, were costly. The “furniture” on Mr. Wells’s best bed referred to the textiles on and around the bed and included the best bed quilt, three bed blankets, and a good sute [suite] of curtains. He left his wife, in addition, “all the linenin” [linen = sheets, napkins, tablecloths, etc.] in the house, plus all his pewter, all his books, the largest brass kettle, and one-half of all the personal estate that he did not name.

Ebenezer Wells names as his second inheritor, the “Church of Christ in Deerfield.” To them he leaves a “good silver tankard” and charges his executors to see that the tankard is made and presented to the church.

Ordinarily the children of the deceased would be named next. However, Abigail and Ebenezer Wells were childless, so the following bequests were made to Ebenezer’s own siblings or to their children, his nieces and nephews. He leaves to them either property, in the case of the male members, or money to the females. [This is a reminder, once again, that property does not ordinarily descend to females in the eighteenth century.]

Mr. Wells concludes the apportionments in his will by assigning “all the remaining part of my Estate whether Real or Personal that is not already disposed of” [recall that his wife received one-half of his personal estate, i.e. all his possessions except land (real estate)] to his nephew and namesake, Ebenezer Wells, son of “my Brother Thos Wells Late of Deerfield deceased.”

He lastly names his “Beloved wife Abigail” and his nephew Ebenezer as executors to see that the conditions of the will are followed.

What can you learn by studying an eighteenth-century will? It may be the only record of a person’s existence. He may have left no letters, no diaries or account books. From the will you may learn, as in this case, what he valued most. All his possessions are not listed, as they would more likely be in an inventory, but we do get insight into a portion of the furnishings of the house where Ebenezer and Abigail Wells lived. We know they had a curtained bed and a quantity of linens. They owned pewter, all of which descended to the widow. Several brass kettles must have been in the kitchen, since Mrs. Wells received “the largest” one. And one can assume that more than two chests were in the house, since Abigail received the “two best.” From the bequest of “a good silver tankard” we can infer that Mr. Wells was a member of the church.

This document helps us to reconstruct Mr. Wells’ family – to create, from those named as heirs, who his relatives were, his genealogy. We assume he had no children because none are named. From other sources we know that Ebenezer owned two slaves, Lucy and Cesar. They are not named in the will. Slaves were not freed by Massachusetts’ law until 1783. Lucy married Abijah Prince on May 17, 1756, one year before the will was written and, since she married a free black, probably obtained her freedom at that time. She was undoubtedly gone from the household in 1757. Was Cesar a part of the personal estate left to Abigail or to the nephew Ebenezer? We cannot know without an inventory.

Although the book titles are not named, Mr. Wells thought enough of his library to leave it all to his wife. No ceramic ware is mentioned. Pewter, common on tables in the first half of the eighteenth century, stayed in the house since it was given to Mrs. Wells. And she received the two best chests to house “all the linenin in the house whether wrought or unwrought.”

Mrs. Wells was given the “use and improvement of one-half of [the] real estate.” This meant that, although she did not own the house, she could continue to live there with Ebenezer Wells, her husband’s nephew as the owner. Ebenezer, born in 1730, married June 20, 1757, a little more than a month after the will was written. He and his wife must have moved into the house on Lot 26, at the corner of Memorial Street and Deerfield’s main street soon after the senior Ebenezer died on June 12, 1758.