Inventories are lists of possessions, with current values, of both real and personal property [real estate and personal estate] owned by heads of household at the time of death. If the inventories were submitted to probate court, as most but not all of them were, they were considered approved by the court and filed there.

Such inventories were taken routinely from the earliest years of English settlement, but not every resident’s estate in every town was inventoried. Inventories were not for tax purposes, in those days before federal income taxes were levied, but rather for insuring that debts against the man’s estate were paid. Cash was usually not readily available and that meant that part of the estate might have to be sold to reconcile the debts. Generally, three men were appointed to take an inventory and often at least one of the men was knowledgeable about the occupation of the deceased to insure that the tools could be properly named.

For historians, probate inventories are valuable tools, offering insights into material culture and into the economic development of a society or of a particular family at a given point in time. What a person owned and the value attached to it reveals clues about life in earlier times not available from any other source.

There are, however, precautions that should be taken in the use of inventories for research. A person’s net worth at death did not always give a true picture of his means for most of his life. Some possessions may have been given away before the death of the giver or assigned to an heir and therefore exempted from the list. For example, a man might have given away or sold the tools of his trade after he no longer worked at that trade, perhaps well before he died, or a favored relative might be granted an article or articles outright and, therefore, such items would not be listed in the inventory. Also, objects might well be overlooked or misnamed by the appraisers.

The season of the year in which the inventory was taken should always be considered, particularly in a farming community since grain, produce, etc. will be counted in storage in fall, winter, and late spring, but will be growing in the fields and, therefore, largely absent in the storage areas in the summer months.

The real estate – property – including the homelot is usually listed first, with household goods and personal possessions following. Ordinarily the more valuable items – silver, clocks, and textiles – are named first, but this is not always true. Before 1790 – 1800, values are listed in English pounds, shillings, and pence; after that they are ordinarily listed in dollar amounts. It is convenient for the historian when the appraisers list the objects room by room, since then one can reconstruct the furnishing plan of the house, but this is not always the case. Generally the assets are totaled and the appraisers are listed at the end of the enumeration of possessions. Next is a list of the debts due to the estate and a list of debts owed by the deceased. A true total is then rendered.

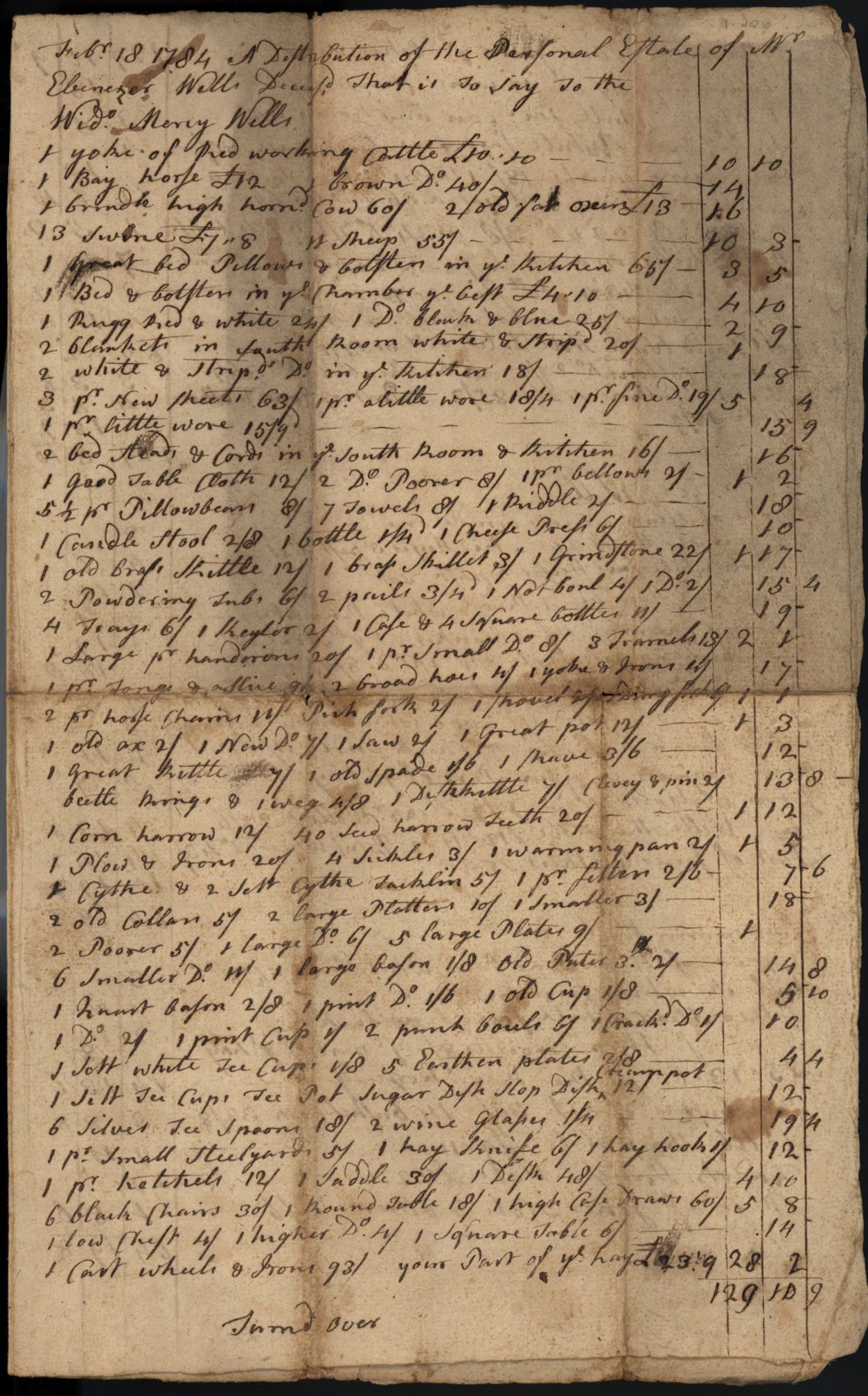

The inventory of Ebenezer Wells (1730-1783) of Deerfield, Massachusetts was probated in Hampshire County Court. Although Deerfield is now in the county of Franklin, before 1811 it was a part of Old Hampshire County, which extended from the Vermont border to Connecticut. The probate court was located in Northampton.

Probated February 3, 1784, the estate inventory of Ebenezer Wells begins in an orderly fashion with the listing of the real estate – fifteen parcels in all; the homelot, [#26 on the Deerfield Street] is named first. The other parcels include land in Deerfield and in the adjacent town of Conway; both pastureland and woodlots are named. Included is half-interest in a sawmill in Conway and the “Privilege of the Stream forever.” It was not uncommon for men in the eighteenth century to own parts or shares in enterprises such as sawmills.

The appraisers then list the livestock. The number of animals provides evidence that Mr. Wells was a farmer. He owned twenty-five heads of cattle, which included a yoke of steers worth 100 shillings and a yoke of fat oxen at thirteen pounds. Three horses and a colt, thirty-four sheep, and thirteen swine complete the tally of farm animals. Feed for the animals are listed next; also in the barn where the animal provender was stored is listed 130 pounds of “flax in the bundle.” Flax is the raw material from which linen is spun, and many families raised enough raw material to supply their own needs. In this period clothing and bedding were most often made of wool from the sheep and of linen from flax.

The next item, a desk valued at forty-eight shillings, suggests that the appraisers were now in the house. They go on to list chairs, tables, and chests, but then revert to farm equipment – hoes, yoak [yoke] and irons, pitch fork – then kitchen equipment such as a dish kettle and iron kittle [kettle] and back to old spade, plough irons, and sicles [sickles]. What must we conclude? – that the men were walking back and forth between the barn and the house or that the kitchen and [probably] the shed contained equipment for cooking as well as farm tools. Probably the latter answer is the true one.

After “2 old Collars” [for horses? – possibly hanging on the wall of the shed or the barn] we are certain they are inside the house since the first line includes a trundle bed and bolsters, great bed pillows and bolsters, followed by bedquilts, bedrugs, blankets, bedsteads and cords – six beds in all in addition to the trundle. The term bedstead is a familiar one and refers to the wooden bed frame, but “cord” is not a word used in the twenty-first century when referring to beds. The “cords” are the ropes that are laced between the side rails and the head and foot rails to form a support for the “bed” or mattress. It would be nearly impossible to have six beds set up in one room, so it would seem that the appraisers were wandering through the house tallying objects, but not walking from room to room in a progressive way.

What follows is a mixture of fireplace equipment (pair cobb irons, pr tongs & slice), textiles (18 pair sheets, table cloth, pillow beers), items of clothing (great coat, velvet jacket), spinning and weaving equipment, and table ware, both pewter (large bason, old pewter) and ceramic (sett TeaCups, cream pot). Six silver teaspoons are listed near the end, followed by “2 wine glasses” and then, surprisingly, a hayknife, hayhook, hechels, saddle, and finally “2000 feet White pine boards” [in the garrett, perhaps?].

In order to aid in the understanding of the estate of Ebenezer Wells, it will help to examine the number of children born to the couple and how many family members were living in the house at the time of his death in 1783. Mr. Wells had married Mercy Bardwell (1737-1801), of Deerfield, Massachusetts on June 20, 1757. They had nine children born from April 19, 1758 to February 1, 1774. In 1783, the year of the father’s death, the children ranged in age from twenty-five-year-old Ebenezer to nine-year-old David. True to the pattern in the eighteenth century, the first child was born in the first year of marriage and successive births were every two years. What was unusual was that all nine were live births; the only child who did not live to full maturity was Zeeb, who died at age seventeen, four years before his father.

Mercy Bardwell was twenty years old when she married and she bore her last child at age thirty-seven. Ebenezer, the oldest son did not marry until 1786, and George Sheldon, in his History of Deerfield, tells us that he was a silversmith who kept shop both on Lot 35 (Col. David Field’s store) and on his father’s homestead. Ebenezer, then, was still at home in 1783 at age twenty-five. The second son, Benjamin, had married in 1782 and settled in Conway and Zeeb, born 1762, had died in 1779. The fourth son Quartus, born 1764, was at home with Sarah, age seventeen; Mercy, age fifteen; Thomas, age thirteen; Samuel, age eleven; and David, age nine. This means that, in addition to Mrs. Wells, we can assume there were seven children living in the house on the Deerfield Street in 1783. The house, at that time, had six rooms, a full cellar and a large attic situated on slightly more than four acres stretching from the main street to the woodlot on Pocumtuck Mountain.

The names of the debtors and those to whom money is owed help the researcher/historian to understand something about those members of the community and provide a glimpse into the state of the local economy. Many people leave no paper records of their own, but are recorded only in the papers of others. That evidence validates their existence and allows them to be put into a time and a place. Every document from the past has virtue; it is up to the researcher to fathom how it can help further his knowledge of what has gone before.