Indigenous peoples, along with European inhabitants of northeastern North America endured an almost constant period of warfare throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. One conflict flowed into another as these groups sought to strengthen or maintain their positions in an ever-shifting world of political alliances. Age-old political, economic, and religious animosities between England and France spilled over to their colonial possessions. Meanwhile, Indigenous peoples reeling from the effects of disease and invasion, strove to maintain or establish alliances and trade patterns, and preserve their homelands.

It was in this atmosphere of political instability and violence that northern peoples such as the Abenaki, Penacook, Wendat (Huron) and Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) came south with their French allies to attack English settlements. Hundreds of English men, women, and children experienced the terror of being “captivated” and carried away to Canada. A tiny number of captives, especially young girls, successfully integrated into Indigenous communities. Among those who returned to New England, some maintained contact with their former captors and some men served as scouts and interpreters for the English military when they were in Indigenous lands.

A good example of those who bridged two worlds are the Kellogg siblings. Martin, Jr., Joseph, and Rebecca were captured during a 1704 raid on Deerfield, Massachusetts, and each eventually returned to their English world. Eighteen-year-old Martin, Jr. escaped after several months of captivity but was captured again in 1708. This time he stayed in Canada for several years and learned to speak French and at least one of the Indigenous languages. When he returned to Massachusetts he worked for the colony as an interpreter and traveled back to Canada in 1714, to help redeem captives, including his brother Joseph. Years later Martin moved to Connecticut and 12 boys from the Hollis School for Indigenous boys in Newington, Connecticut, were sent to live with him for three years. He then became a teacher and interpreter at the school.

Joseph spent 10 years in captivity in Canada with the French and Indigenous peoples. He learned French and several Indigenous languages and when he returned, he joined his brother working for the colony as an interpreter, messenger, and scout. Joseph tried for years to redeem Rebecca and their sister Joanna. His efforts failed with Joanna, but he finally succeeded in bringing Rebecca home. He served as a captain in the military and in 1740, was assigned by the Massachusetts colony to be the chief interpreter with the Indigenous peoples. He also served as an interpreter for a church for the Mohawk people in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and he succeeded Martin, Jr. at the Hollis School.

Rebecca was captured at the age of nine and was 34 years old when Joseph brought her home. She had been married, living in the Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) community of Kahnawake. She remarried Benjamin Ashley of Westfield, Massachusetts, and both worked at the Stockbridge, Massachusetts, school for Indigenous children. She was an interpreter there and several other places. In 1753, Rebecca and Benjamin traveled with a minister to Ouquaga, New York, where she served as the minister’s interpreter for the Iroquoian peoples. They called Rebecca “Waskonhon,” which means “the bridge,” and mourned her when she died there in 1757. The minister wrote that she was a “very good sort of woman, and an extraordinary interpreter in the Iroquois language.” She had, indeed, served as a valuable bridge between the Indigenous peoples and the English.

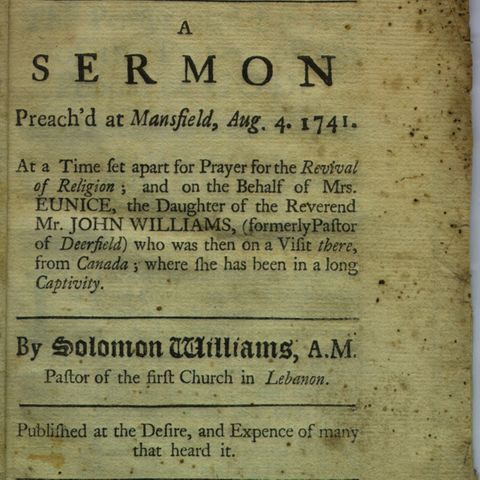

The sash pictured was a gift from the Kanien’kehaka husband of an unredeemed captive to her brother. Both Eunice and Stephen Williams had been captured in 1704, but she chose to remain while Stephen returned to the English world. Eunice was seven years old when captured and was adopted by a family in Kahnawake. Despite several visits from her English father, the Reverend John Williams, who pleaded with her to return to her English home, she resolutely refused. She married a man from Kahnawake and converted to Catholicism. Eunice, known by her Kanien’kehaka family as “Kanenstenhawi,” was less of a bridge than Rebecca Kellogg between two cultures, but she strove to maintain ties between her two families. Kanenstenhawi and her husband Arosen made occasional visits to Stephen, who was a minister in Longmeadow, Massachusetts, until the French and Indian War (1754-1763) made travel too dangerous. Arosen gave this fingerwoven sash to Stephen during one of these visits.