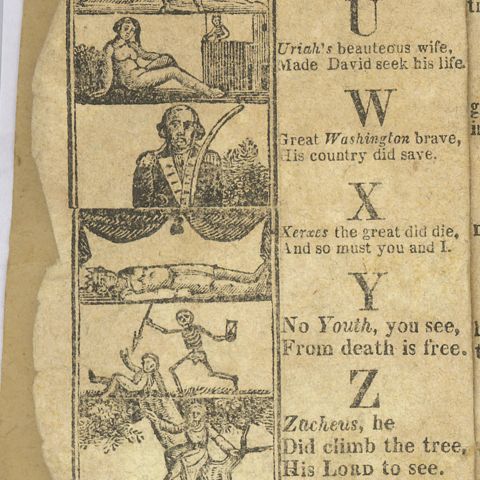

People in the 1700s lived in a primarily oral culture. Religious beliefs, however, led to relatively high literacy rates among early New England Protestants and their European counterparts. The belief that lay people as well as clergy should be able to read the Bible defined the Protestant Reformation from its beginnings in the fifteenth century. Massachusetts Bay Colony required in 1648 that every town of fifty families or more provide a school “it beiing one cheife project of yt ould deluder, Sathan, to keepe men from the knowledge of ye Scriptures.”

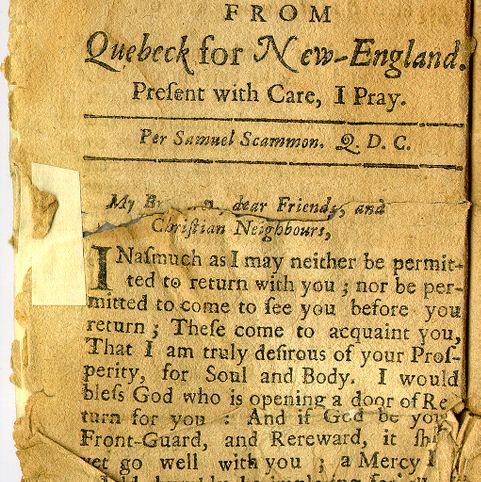

In contrast, the government of New France, or Canada, discouraged literacy among common people, believing it made them dissatisfied and rebellious. Governor Sir William Berkeley of the Virginia colony agreed, writing in 1671, “I thank God there are no free schools nor printing, and I hope we shall not these hundred years, for learning has brought disobedience and heresy, and sects into this world, and printing has divulged them….” Educational opportunities in the South remained comparatively sparse throughout the colonial period.

Economic and political factors also stimulated literacy as the eighteenth century wore on. Sending and receiving letters, reading a deed, and keeping accounts all required basic literacy. The political pamphlet was an important literary form in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Widespread literacy allowed colonists to steep themselves in a political ideology that stimulated first an imperial crisis and then a revolution.

Although literacy for women lagged behind male literacy levels, many more women could read and write in New England than in England and other countries. This book, The Reformed Pastor, belonged to Hannah Beaman (1646-1739) of Deerfield, Massachusetts. The author was Richard Baxter, a Puritan minister and a chaplain in Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army during the English Civil War. We know Hannah could read and write not only because she wrote her name on this book, but also because she kept a dame school in the 1690s. Women generally taught dame schools for younger scholars, some as young as two or three years old.