1775

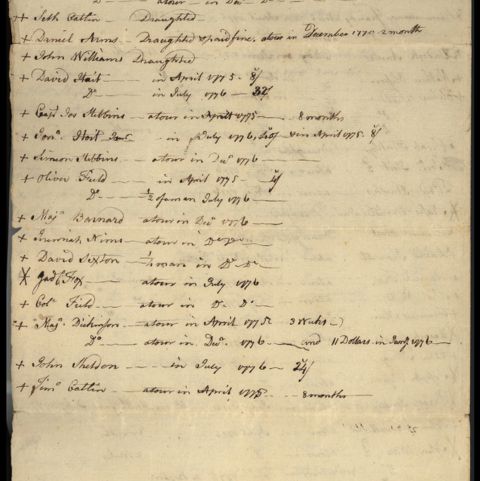

Years of protest, rising tension, and increasing violence between Great Britain and 13 of its North American colonies became open warfare on April 19, 1775. Hundreds of Minuteman militia companies throughout New England marched toward Boston as news spread of the fighting at Lexington and Concord. Fifty Deerfield, Massachusetts, marched to Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 20 where they joined thousands of other New Englanders besieging the British troops now bottled up in Boston.

Less than three weeks after the “shot heard round the world” Colonel Benedict Arnold of New London, Connecticut, rode into Deerfield. He arrived with orders from the Massachusetts government to raise 400 men and supplies to attack British-held Fort Ticonderoga in New York. After provisioning his expedition with 15,000 pounds of Deerfield beef, Arnold hurried off to make history, although not quite as he had planned. When he arrived to take command, he discovered that Ethan Allen, another Connecticut native, was already on the scene. Allen’s presence and personal popularity among his men spelled disappointment for Arnold, who had to settle for a joint operation led by Allen. The Americans had the advantage of complete surprise when they attacked the lightly-defended fort in the middle of the night on May 10. They captured the fort with all its ammunition, supplies, and cannon without having to fire a single shot.

That fall, General George Washington sent Colonel Henry Knox of Boston to Fort Ticonderoga with orders to bring the artillery to Boston. It took Knox just fifty-six days to transport 60 tons of cannon and other military supplies 300 miles using boats and sledges pulled by men, horses, and oxen across frozen lakes and rivers, trails, forests, and swamps. Modern markers along what is now called the Knox Cannon Trail are placed along the route that stretches from western New York and across Massachusetts to Boston.

1776

In January 1776, General Henry Knox arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with the cannon captured at Fort Ticonderoga. General Washington ordered them to be placed on Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston, forcing the British army to abandon the city in March, 1776.

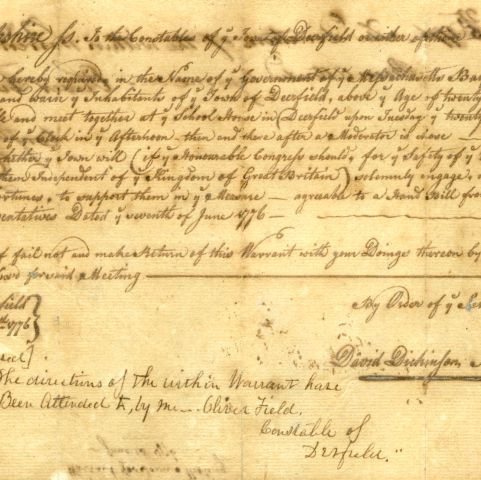

Deerfield was one of many Massachusetts towns that passed resolutions that summer urging the United States to declare independence from Great Britain. A majority of Deerfield voters resolved on June 25 that, should the Continental Congress vote for independence, the town of Deerfield would “Solemnly Engage with their Lives and Fortunes to support them in ye Measure…”

Meanwhile, town residents were deeply divided between those who wanted to remain part of the British empire and those who saw American independence as the obvious goal. At the end of the year, members of Deerfield’s Committee of Correspondence, Inspection, and Safety voted to confiscate and sell at auction Nathaniel Dickinson’s substantial farm at Mill River. The committee declared Dickinson had “joined our unnatural enemies for the purpose of aiding and assisting them in subjugating these American Colonies.” All of Nathaniel’s property, including livestock and household items, were auctioned and the profits paid into the Massachusetts treasury. An outspoken loyalist, Dickinson apparently ended his days in New Brunswick, one of the estimated 65-80,000 Loyalists who chose exile over repudiating their identity as British subjects. Meanwhile, Nathaniel’s own brother and other Dickinson family members were ardent Patriots—just one of many examples of how the question of independence divided American families as well as communities.

Deerfield was not the only town moving against its Loyalist residents. In June 1776, the neighboring town of Conway voted in a special town meeting that 12 men in town were “Dangerously Enemical to the american states” and began collecting the necessary evidence to lay before the court. By late August, anxieties over these and other Conway Loyalists reached a fever pitch. At a town meeting held in the meetinghouse, the town “Voted to proceed in some measures to Secure the Enemical persons called Torys amongst us—then the Question was put whether we would Draw a line Between ye Continant and Great Briton voted in the affirmative. that all those Persons that Stand on the Side of the Continant [the American cause] Take up arms and go on hand in hand with us in Carrying on the war against our Unnatural Enemies Such we perceive as Friends and all others treat as Enemies.” To identify such “Unnatural Enemies” Conway voters set the center aisle of the meetinghouse as a line between those on the American side and the British Side. The meeting minutes recorded the names of the six men who chose stand “on the British Side.” The last business before adjourning was “to set a gard over these Enemical persons” and to instruct the Town Clerk to ask a Judge to arrest all six men.

By the end of the year, the first burst of American energy and patriotism was flagging. Chased out of New York in a series of disastrous engagements, the Continental Army retreated to Pennsylvania. The ragtag army under General George Washington was shrinking day by day. In December, Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, The American Crisis was read and passed among the soldiers in an effort to boost failing morale. Paine wrote,

These are the times that try men’s souls; the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

On Christmas Day 1776, as short term enlistments were about to run out, George Washington famously crossed with his army across the icy Delaware River from Pennsylvania into New Jersey where he defeated a garrison of Hessian troops the following day. Washington quickly followed up with a successful attack on a British force at Princeton. These small but strategic victories helped restore hope and energy among American revolutionaries.

1777

Many Connecticut Valley men actively participated as soldiers during the war, while others avoided military service when possible. Most served in the American militia or Continental Army, but a few decided they would rather fight with the British. Among them was Phineas Munn of Deerfield, who had been outspoken enough already in his political views to have been mobbed as a Tory in 1774. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Munn fled Deerfield in September 1777 to seek refuge in New York with the British army invading from Canada. When it became clear the Americans were surrounding Burgoyne’s army, Munn apparently made his way to Montreal, Canada, for the winter. He was on his way back to Deerfield when a Committee of Correspondence picked him up in Concord, New Hampshire, interrogated him, and sent him to jail in Northampton. By 1778, Munn was back in Deerfield with his wife and children, where he remained until his death in 1820, aged 84.

Most of Munn’s neighbors responded very differently when they found out a British force of almost 8,000 men under the command of General John Burgoyne was on the march. The news roused terror and urgency throughout New England. If Burgoyne succeeded, all of New England would be cut off from the other states and at the mercy of the invading army. According to Epaphras Hoyt of Deerfield, “On the near approach of Genl Burgoynes Army the call was general, and many took the field with determined spirits…The approach of the British Army created apprehension among the inhabitants…we were admonished by the thunder of the artillery at Bennington, which I very distinctly heard, that our peaceful fields might soon be rolled in garments of blood…”

Men from Deerfield and surrounding towns were among the thousands of New England militia who flooded into Vermont and New York in the fall of 1777 to defend New England, even though it was harvest season, a time when it was typically notoriously difficult to recruit militia. Militia from Montague refused to march, however, until the town had rounded up, disarmed, and placed under guard 19 suspected Tories “being greatly Apprehensive of danger ensuing if these persons…are left at home armed.” Western Massachusetts militia famously helped to defeat the British army at Saratoga, New York, a crucial victory that encouraged France to join the war on the American side.

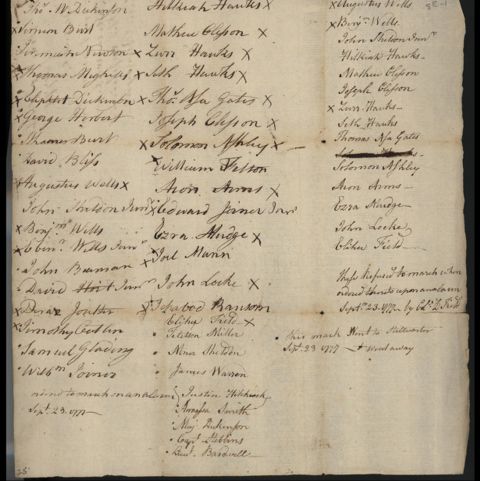

Even so, a roster of Deerfield men who responded to the call for militia to go to New York listed several men who, like the 19 Montague Loyalists, had “refused to march when ordered thereto” by Colonel David Field on September 23. Although many men had been willing to turn out to protect their homes and families from the threat of invasion in the northern campaign, a resident later recalled,

the presence of the war in subsequent years nearly extinguished their zeal, and that to furnish recruits for the Continental army was a difficult task…The people of the several towns were…compelled to furnish our armies recruits…by hiring or draft… One grand objection of our young men to enlisting into the Continental army was the fear of the rigid discipline imposed by its officers. In the true spirit of militiamen they believed this discipline to be totally unnecessary, and that men could be led up to the cannon mouth by soft pursuation…

On the homefront, Deerfield residents continued to struggle over the question of what to do with their outspokenly Loyalist minister. The Deerfield church had ordained Ashley as the town’s minister in 1732, when he was only 20 years old. Like many clergy in Western Massachusetts, he was in favor of law, order, and obedience. A revolution is none of those things, and Ashley staunchly opposed it. He had prayed publicly for the king of England for forty years and saw no reason to stop. Ashley remained loyal to Britain and refused to be silenced despite the town’s multiple attempts to fire him, as well as refusing to supply vote his firewood allowance or pay his salary.

1778

Thanks to the American victory at Saratoga in which Deerfield and other western Massachusetts communities played an important role, France signed a treaty of alliance with the new United States. The French alliance included promises of continued military and financial support for the Revolution. The American Revolution became an international war when France declared war on England in July, 1778; Spain would join the American cause against Britain in 1779.

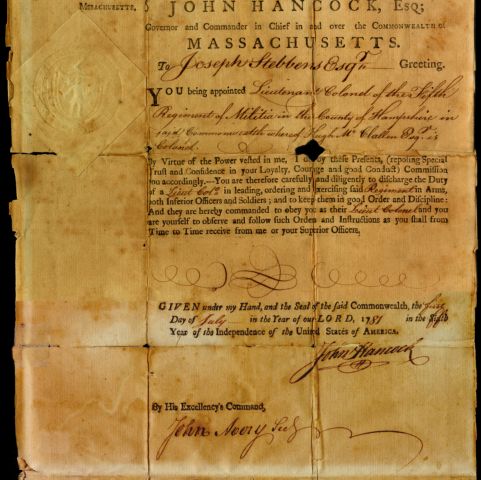

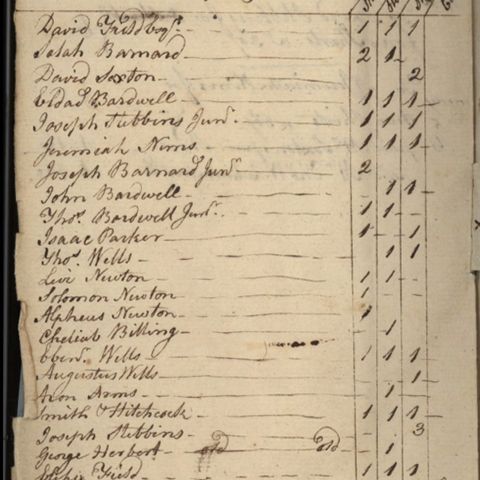

Deerfield and other Massachusetts towns were expected to continue recruiting men to serve in the army according to a quota established by the state. If a town did not meet its quota, men who had not already volunteered were ordered to serve or pay a hefty fine. In June, 60-year-old Joseph Stebbins, Senior, was drafted for a nine-month tour in the Continental Army “or pay a fine of twenty pounds within twenty-four hours.” Stebbins paid the fine. Later that month, Deerfield was ordered to provide 34 pairs of shoes, stockings, and shirts. Such requirements are a reminder of the important role women played in the war. They furnished essential supplies that included knitting and sewing essential clothing for militia and Continental Army soldiers, in addition to running farms and businesses while spouses were absent for months or years at a time. Meanwhile, the town of Deerfield again voted against raising the Reverend Ashley’s salary or to supply his household with firewood.

1779

By 1779, the war was in its fourth year and the first burst of energy and enthusiastic patriotism of 1775 and 1776 was in the past. Now it was more like steady pulling with a heavy load, and it required strong determination to sustain the fight. At least nineteen Deerfield men served in the army that year, but Patriots were becoming discouraged while middle-grounders and the indifferent were weary of war. The Loyalist faction in Deerfield capitalized on this mindset and gathered strength. Town meetings were frequent and stormy. In March 1779, the Whigs (Patriots) filled the leading offices and conducted business as usual. But, at an adjourned meeting, the Loyalists (Tories) gained control and tried to undo all that had been done at the first meeting. In December, the Tory-controlled town meeting voted to supply the minister with firewood, which must have been a relief to his family.

1780

The winter of 1779-1780 was called “the hard winter,” one of the coldest in American history. Poorly supplied and clothed, American army suffered from starvation, disease, and exposure. Warmer weather did not bring better fortune. In May 1780, the Americans suffered one of their worst defeats of the war when the British captured Charlestown, South Carolina, along with the American army that had unsuccessfully tried to defend the city. In the same month, Connecticut troops mutinied at Fort Stanwix, New York, over lack of food and other supplies. A Connecticut private, Joseph Plumb Martin recalled,

The men were now exasperated beyond endurance; they could not stand it any longer. They saw no alternative but to starve to death, or break up the army, give all up and go home. This was a hard matter for the soldiers to think upon. They were truly patriotic, they loved their country, and they had already suffered everything short of death in its cause; and now, after such extreme hardships to give up all was too much, but to starve to death was too much also. What was to be done? Here was the army starved and naked, and there their country sitting still and expecting the army to do notable things while fainting from sheer starvation. All things considered, the army was not to be blamed. Reader, suffer what we did and you will say so, too.

The mutiny was put down but there would be other mutinies among New Jersey and Pennsylvania regiments that winter. In September, Americans reeled under the disastrous news that one of their most talented generals, General Benedict Arnold, had committed treason. Five years after his dashing entrance into Deerfield, Arnold was disillusioned and angered by what he saw as a lack of recognition and promotion. In the months following his brilliant leadership at the Battle of Saratoga, Arnold made the fateful decision to begin passing military information to British agents. When his treachery was discovered on September 23, Arnold fled from West Point, New York, and took up arms against the revolution he had once fervently supported. Arnold’s treason devastated already-low American morale.

Deerfield’s controversial minister, Jonathan Ashley, died in 1780 at age 68, leaving his estate to his elderly widow and their adult children. The town had paid little of Ashley’s salary during the war. Those in charge of settling his estate brought a large claim against the town, declaring that he was owed 787 pounds, 17 shillings, and 6 pence for years of unpaid salary, firewood, and rent of the town lot. Ashley’s death seemed to have reduced the tension, as Deerfield agreed to pay these debts with very little murmuring.

1781

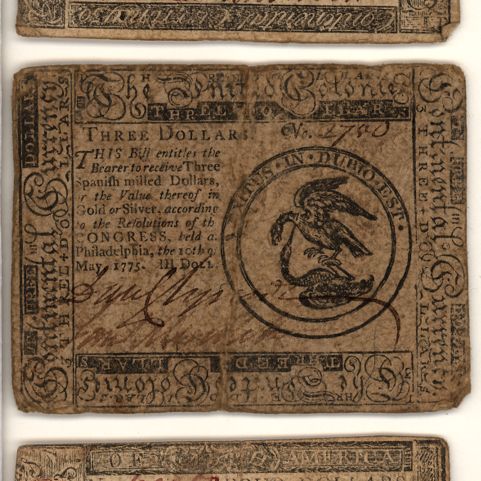

After six years of conflict, the end of the war seemed nowhere in sight. Americans struggled to make ends meet and were heartily weary of war. Hundreds of millions of dollars of paper money printed by Congress and the state governments were virtually worthless and the economy was near collapse. Towns struggled to meet their recruitment quotas and turned to paying bounties to men willing to enlist for three years or the duration of the war. Thirty-two-year-old Caesar Bailey was among 32 men who joined the Continental Army from Deerfield in 1781. Described as 5 foot 7 inches tall with a black complexion and hair, Bailey enlisted for the duration of the war. Originally enslaved by Nathaniel Dickinson whose estate was confiscated and auctioned five years before, it is not clear whether Bailey was enslaved at the time he enlisted, as he is identified as a farmer and received an enlistment bounty. Caesar Bailey’s service highlights the important role people of color, enslaved and free, played in the American Revolution. By the end of the conflict, an estimated one in five soldiers serving in the Continental Army were African American and Indigenous men.

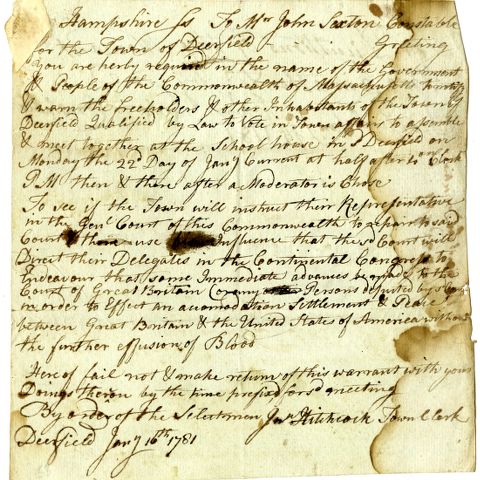

Deerfield’s Loyalist faction narrowly succeeded in passing a town resolution in March 1781 to pursue peace negotiations with Britain. The resolution instructed Deerfield’s representative to the Massachusetts legislature “to Effect an accomodation Settlement & Peace between Great Britain & the United States of America without the further effusion of Blood.” When word reached the Massachusetts General Court (the state legislature), the legislature launched an investigation. A committee reported on what they considered the dangerous state of affairs in Deerfield:

Divers persons, Subjects of this Commonwealth, are Disaffected to the Independence of the United States…and are artfully propagating the most dangerous principles…and are using their utmost efforts to prevent furnishing supplies of Men and provision for the army of the United States and to withdraw the good people of this Commonwealth from their allegiance to the government thereof.

The order went out to bring the ringleaders of the Deerfield resolution—Seth Catlin, John Williams and Jonathan Ashley, Jr.—to Boston to face charges of treason. They were summarily carted off to jail and a trial in Boston. The General Court determined that the three were indeed “unfriendly to the independence of the United States.” In a show of defiance, Deerfield’s Loyalists made a point of voting Jonathan Ashley, Jr., in as both town clerk and treasurer but within weeks all the Loyalist office holders resigned as the heavy hand of the Massachusetts government came down. All office holders were required to take an oath of loyalty to the state. Catlin, Williams, and Ashley petitioned for release, pleading ill health and hardship to their families. Freed on £2,000 bail after several months in prison, Jonathan Ashley, Jr. died soon after and John Williams’ health was permanently affected. That spring, John Williams and Seth Catlin bowed to the inevitable and took the oath of allegiance to the Massachusetts government:

I who subscribe, do truly and sincerely acknowledge, profess, testify and declare, that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is, and of Right ought to be, a free, sovereign, and independent State, and I do swear, that I will bear true Faith and Allegiance, to the said Commonwealth,and that I will defend the same against traiterous Conspiracies and all hostile Attempts whatsoever: and that I do renounce and abjure all Allegiance, Subjection, and Obedience to the King of Great Britain–and every other foreign power whatsoever…

The year 1781 had gotten off to a gloomy start, but the scene changed dramatically when George Washington led his army to a stunning victory over General Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, in October. Washington’s victory dealt a final blow to any remaining Loyalist hopes for an eventual British victory. The British army’s complete defeat by combined American and French forces spelled the end for Britain’s plans to crush the American rebellion and retain the thirteen colonies as part of the Empire. The British prime minister, Lord North cried, “My God! It is all over!” when he learned of Yorktown, and popular support for the war among the British people evaporated.

1782-1783

Despite the American success at Yorktown, the war would drag on for another two years, making the Revolution one of the longest wars in American history. Rumors of peace raced through the Continental Army in the spring of 1783. Soldiers and civilians alike rejoiced. The army could be disbanded; officers and enlisted men could go home. Private Thomas Foster of Massachusetts recorded in his diary the two questions seemed to be on every soldier’s mind: “when do you expect to be discharged and go home and be rid of this army”? and, “how we are to be paid off”? The bad news was that eight exhausting years of conflict had left every state, including Massachusetts, and the new United States with empty treasuries and a staggering war debt. In the years following the Revolution Deerfield and other communities would struggle to re-form as Patriots and former Loyalists alike joined together to shape the new nation.