Mutual indebtedness was the rule in early America. Because there was little hard cash available until the 1850s, an elaborate system of credit evolved to work around the constant shortage of cash in the form of silver or gold coins. People exchanged goods and services and balanced accounts with small amounts of cash, paper money, or personal “notes” promising to pay a creditor on a specific date in the future. A good credit reputation was essential; to be a person of “no account” made participating in this credit-driven economy difficult or even impossible.

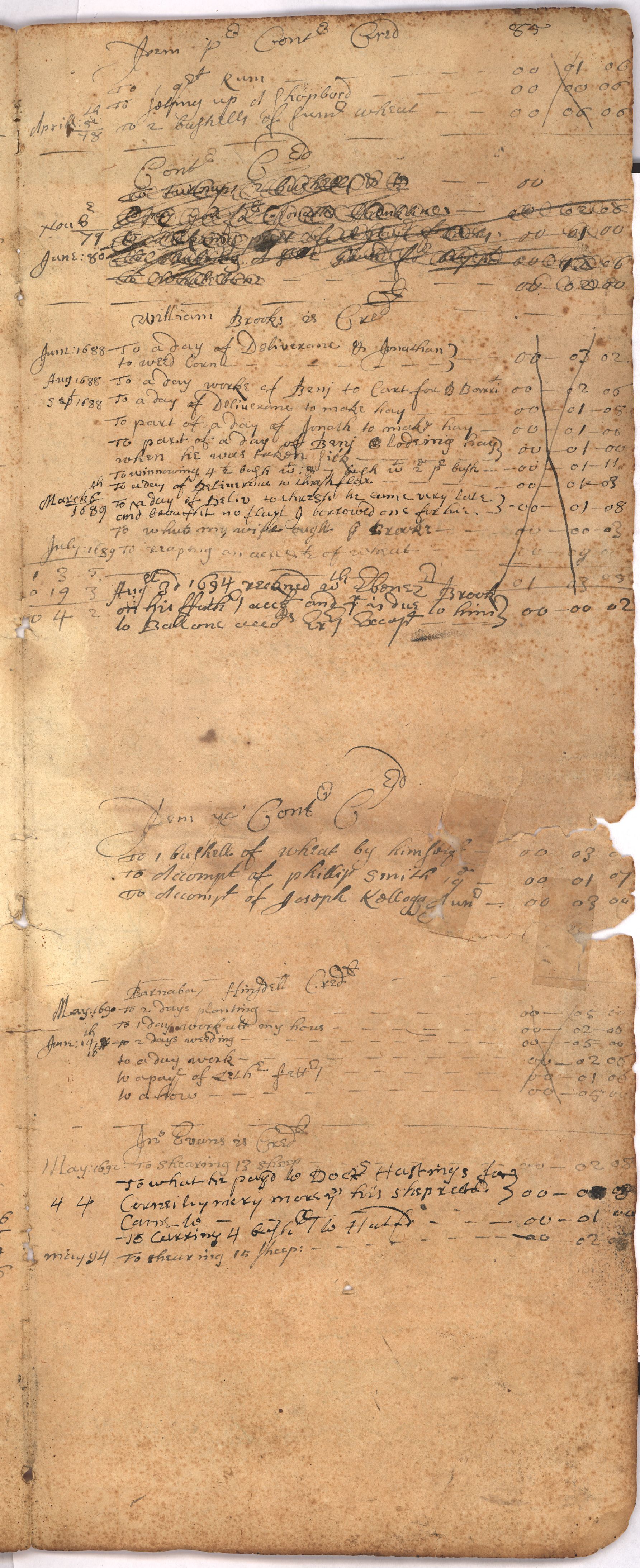

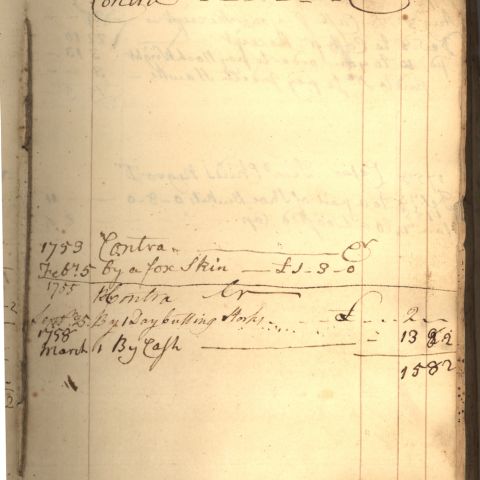

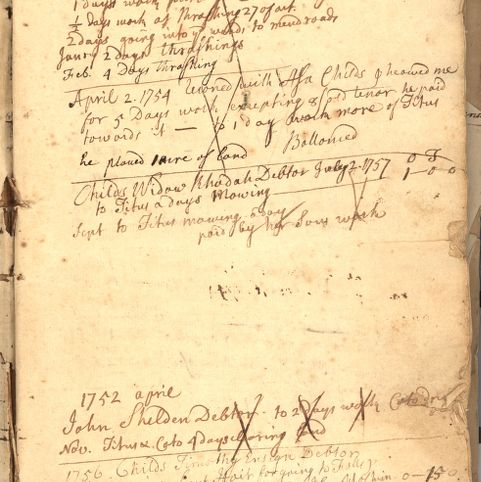

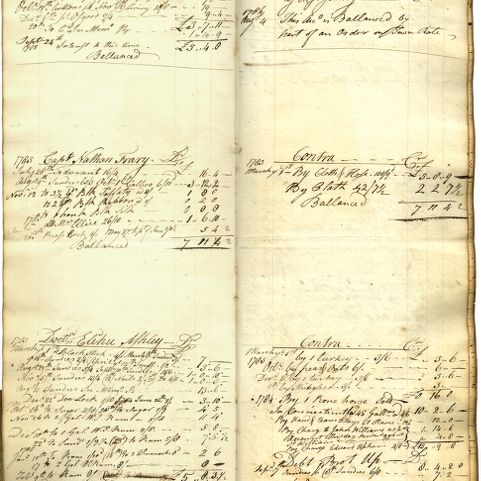

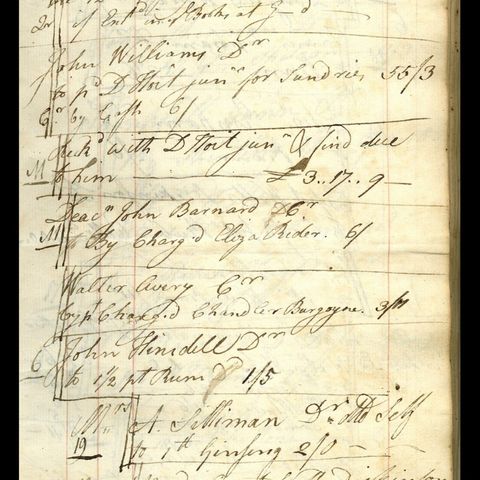

Many New Englanders purchased blank ledger books to record and keep track of their finances. The entries they made in their account books helped them to keep track of what they purchased, including goods and services or money they borrowed. It also recorded who purchased goods and services or borrowed money from them. Until about 1800, the value of purchases were recorded in English pounds, shillings and pence. After that time, Americans increasingly used dollars and cents in their accounting.

Keeping accurate accounts required literacy, good math skills, and diligence. Each individual transaction for goods and services was carefully recorded in the account book and assigned a monetary value. To aid them in keeping accounts accurate and up to date, people often jotted down day-to-day transactions in daybooks, blotters, and waste books. These records provided the raw information that was subsequently entered into an account book ledger using a “double entry” system.”

Developed by Italian merchants in the 14th century and still in use today, double entry refers to keeping a balance sheet tracking debits and credits. The left page of the double entry ledger was the “Dr” or “debtor” side of the transaction. The keeper of the account book wrote the purchaser’s name, the date of the purchase, what the debtor bought, and its monetary value. The right hand page of the ledger was the “Cr” or “Creditor” side of the transaction. This is where the keeper of the account book recorded any payment received from the purchaser, the date of the payment, and its monetary value. In this way, the account book tracked the details of any given transaction and upon adding up the debits and credits, if the account book owner owed a trading partner money or vice versa.

The same system was used by the other party, whose account book entries were supposed to match those of their trading partner. Most payments recorded as credits were in goods and services, although small amounts of cash frequently made an appearance, often in balancing an account. Depending on the relationship between the two parties, accounts were typically reconciled within six or eight months, although in some cases accounts were not balanced and cleared for years. Account books were admissible as court evidence in cases where a creditor sued a debtor for non-payment of a debt. Lawsuits for debt were common in New England courts, comprising the bulk of most lawyers’ practice.

Thousands of surviving account books provide historians and other researchers valuable information about the economic activity of the people who owned them and those who traded with them. Because account books frequently listed dozens or even hundreds of economic partners, they are a window onto the economic and social life of a community as a whole, including the presence and activities of those marginalized in traditional histories. Most, although not all, names in account book entries are male. Women’s critical role in producing and consuming goods of all sorts usually appears under accounts headed by a husband, father, or other male relative. Enslaved people appear in account books when their enslavers hired them out to others. Such entries typically record the labor they performed and its monetary value. Enslaved men and women also appear as economic participants. For example, over a dozen enslaved men and women had accounts at Elijah Williams store in Deerfield.