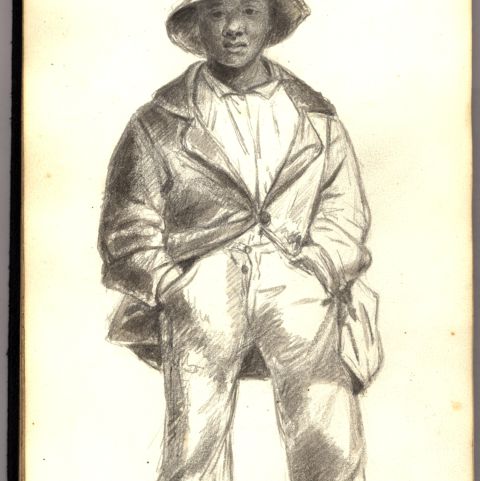

Were it not for his role in the Boston Massacre, most people would likely never have heard of Crispus Attucks. Formerly enslaved, he escaped from Joseph Brown of Framingham, Massachusetts, in 1750. Attucks’ father may have been Prince Jonah, an African man. Prince Jonah’s wife was Nanny Perattucks, of the Nipmuc nation. Crispus Attucks came to Boston and joined the many free Blacks and Native Americans working in the maritime trades. The urban setting and large numbers of people of color working on the docks offered a welcome degree of anonymity to fugitives like Attucks. Tall and powerfully built, he worked for the next twenty years as a sailor, often using the name Michael Johnson as an alias.

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, leaders like Samuel Adams and John Hancock successfully mobilized sailors and dock workers to protest, sometimes violently, against England’s colonial taxation and trade policies. Crispus Attucks was one of many Boston maritime men who were part of the unrest of the 1760s and 1770s between England and her North American colonies.

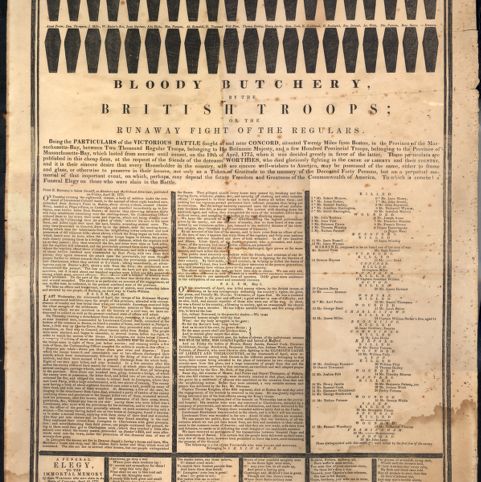

Crispus Attucks was fifty-one years old when he helped to lead a crowd of several hundred angry Bostonians who surrounded British sentries at the Boston Customs House on March 5, 1770, and was one of five men killed when the panicky soldiers fired into the hostile crowd. He and the other victims were instant martyrs to the American cause. Paul Revere engraved a popular print depicting the event and the names of all five men became household words across the colonies. Yet, Paul Revere’s famous print did not depict Attucks as a man of color. Patriots faithfully commemorated the “Boston Massacre” annually in the years leading up to the American Revolution. Attucks’ role in this crucial event raises important questions about people of color in Revolutionary New England culture and society.