During the French and Indian War era, from the late 1600s to the mid-1700s, more than 1,600 White colonists were taken captive by Northeastern Native Americans. The practice of captive-taking in the midst of warfare began long before the arrival of Euro-Americans and persisted into the 1800s as colonists moved westward. The fates of captives varied: some were tortured or killed, some escaped, some were adopted, and some were ransomed back to their families.

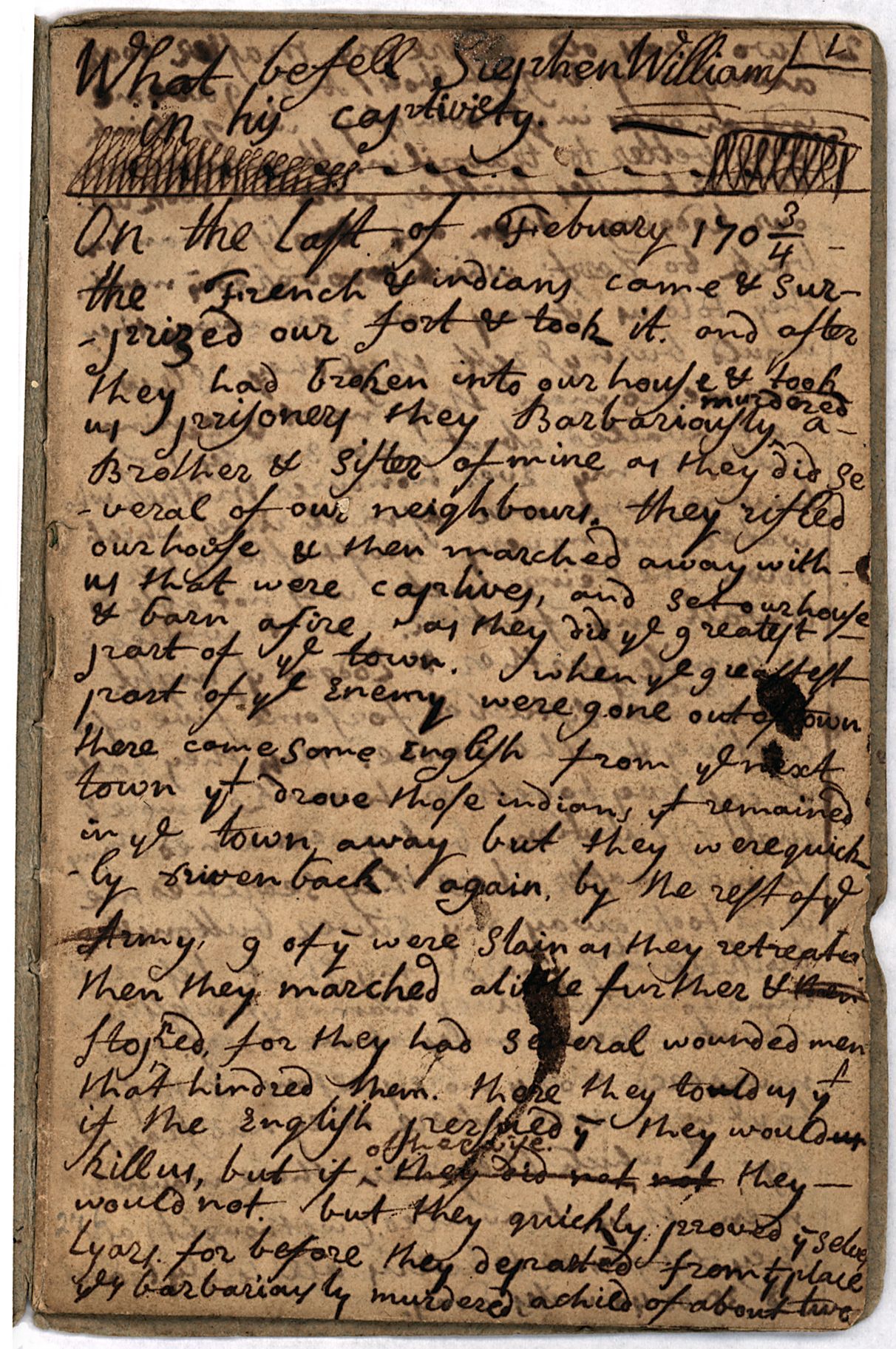

One of the largest captive-taking events of Queen Anne’s War took place in Deerfield, Massachusetts, when the English settlement was attacked in the pre-dawn hours of February 29, 1704. French soldiers from New France (now Canada), accompanied by Abenaki, Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk), and Wendat (Huron) allies, captured 112 Deerfield residents and marched them northward.

From Indigenous perspectives, the act of captive-taking was more than a tactic of revenge against one’s enemies; it was also an opportunity to create new kinship relations. During what were known as “mourning wars,” Kanien’kehaka and Wendat combatants captured enemies to replace loved ones lost through war, illness, or accidents. Captive men might be tortured, but captive women and children were treated with special care as potential kin. Captives who adapted well to their new community might be adopted to take the place of a beloved lost relative. After ritually shedding their original identities, they became “White Indians,” given the same rights and privileges as their new Native kin. If they refused or were not accepted, they might be held for ransom or prisoner exchanges. Most of the Deerfield captives eventually returned, but those who did not became objects of fascination, then and since. After seven-year-old Eunice Williams was captured during the 1704 Deerfield raid, she was adopted by the Kanien’kehaka and eventually married, taking on a new identity and name (Kanenstenhawi). She refused to reunite with her English family, but as an adult, she visited her brother Stephen, camping on the lawn of his house in Longmeadow.

As relieved as some captives were to return home, many were forever changed by their experiences. When a captive returned, they might be wearing unfamiliar clothing or unusual tattoos, and they might have acquired fluency in a different language. Although captive women were never raped, their contact with Native people made them objects of suspicion to their prim English neighbors. Captives who had converted to the Catholic religion, or who had lived in a Native village, were regarded by their neighbors as spiritually and culturally tainted.

A new genre of literature – the “captivity narrative” – emerged as survivors wrote about their experiences, feeding the curiosity of a public fascinated by these cross-cultural interactions. One of the earliest examples is Mary Rowlandson’s The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, published in 1684. Eunice Williams never wrote about herself, but her father, the Reverend John Williams, published his account in 1706, in a book titled The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion, with his son Stephen’s account as an appendix. The Rowlandson and Williams books have been reprinted numerous times and are still attracting new readers today. These accounts have also inspired novels based on captive experiences, notably Mary P. Wells Smith’s The Boy Captive of Old Deerfield, first published in 1939 and still in print today.