Many people, historians and the general public alike, have claimed that Indigneous peoples have vanished, but they have not. Often the superimposition of a more dominant culture obscures or sometimes erases entirely cultural and physical traces. Where is the evidence? It might seem to be nearly invisible unless we are made aware of how and where to look.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Native Americans and Europeans adapted one another’s goods and customs, integrating them into their own belief systems and traditions. One hundred years later, Indigenous people continued to move across their ancient homelands, connected through ties of kinship, culture, and tradition. Few in number and often among the economically deprived, they lived what seemed to their White neighbors to be marginal existences. By the 1780-1820 period in the Pocumtuck homeland, where Deerfield, Massachusetts, now sits, most Pocumtucks had left the area and those that remained lived in a manner similar to their White neighbors. They spoke English and worked as farmers, chair caners, basketmakers, broom makers, bakers, domestic servants, day laborers, and mill workers, among other occupations. They kept alive their traditions even as they sometimes submerged their identities.

Traveling and selling baskets were ways to reinforce connections to the past, to particular people, and to places. The baskets found a ready market among White people.

From the Selected Papers of Sylvester Judd’s Manuscript for the History of Hadley, published in 1905, is the following passage:

There were about these towns when I was young, and sometime built a hut on the edge of the woods or an old field, and lived there, Indian and squaw and sometimes more. They were in Hadley… and made brooms, baskets, mats, and bottomed chairs – all done with wood made into splints. Mrs. Newton of Hadley born 1776 says Indians and squaws peddled brooms and baskets in Hadley when she was young and after. She does not recollect that white people made or peddled brooms.

The American Revolution led Americans to view servitude of all sorts, and especially slavery, in a new light. The institution fell increasingly out of step with the ideals of a new American society based on belief in the essential equality of all men. Many people increasingly viewed it as an inherently evil system that endangered the republican experiment itself. Antislavery societies sprang up in every state. In Massachusetts, a series of court cases put slavery on the defensive by challenging its legality under the state constitution’s declaration that “All men are born free and equal.” Despite these challenges, slavery disappeared only slowly in the North. No Massachusetts law abolished it but a series of court decisions declaring slavery to be unconstitutional under the new state Constitution (1780) led to its gradual disappearance across the Commonwealth through the 1780s and 1790s.

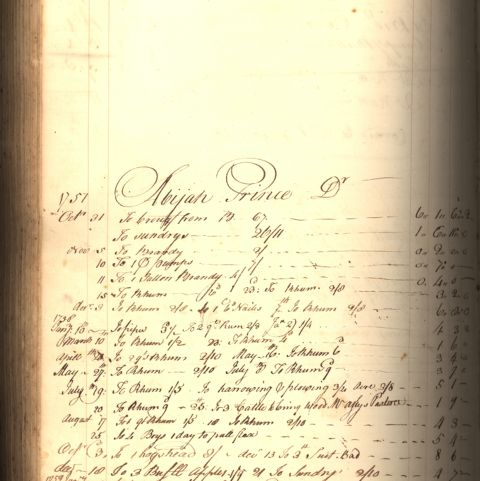

The census reports of 1790, 1800, and 1810 reveal that some of Deerfield’s Black residents lived as boarders on the street and worked as servants or farm laborers. Others owned land and continued to live in the area for a number of years. Most members of the African American community could read and write and their children attended the local schools. Gravestones in local cemeteries mark the sites of burials of those from Black families.