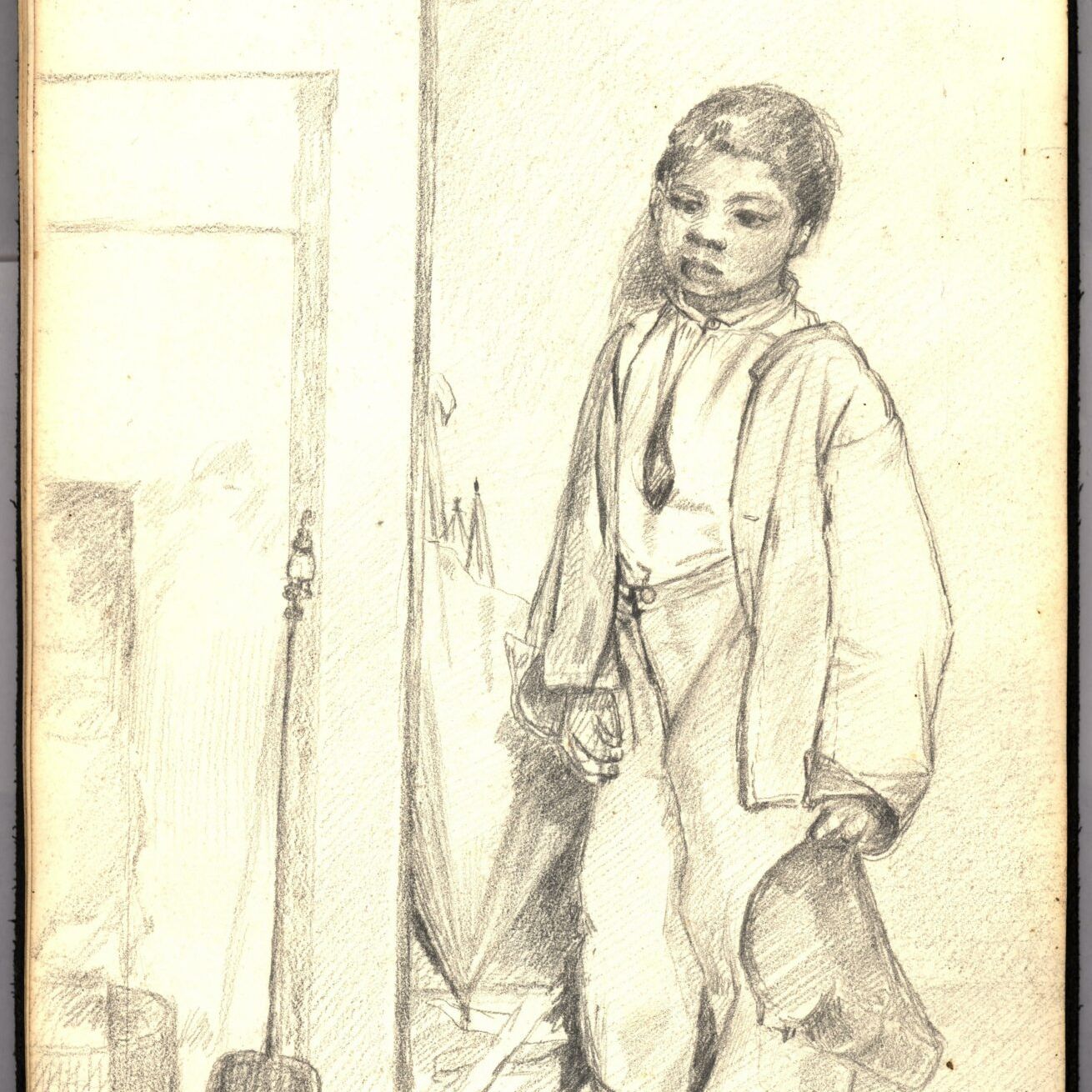

The arrival in 1619 of twenty Africans in Virginia marked the beginning of the forced immigration of millions of Africans to mainland North America. Over the next several decades, chattel slavery became an accepted legal, economic and social component of English colonial society.

The American Revolution (1775-1783) ushered in new beliefs and new ways of looking at society. Its emphasis upon the essential equality of all people and their fundamental right to liberty put slavery on the defensive. Antislavery societies sprang up in every state and several northern states, including New England, enacted gradual emancipation laws. Many such laws, however, deliberately limited access to emancipation; Connecticut, for example, did not fully abolish slavery in the state until 1848. No Massachusetts law abolished slavery but a series of court decisions declaring it to be unconstitutional under the new state Constitution (1780) led to its gradual disappearance across the Commonwealth through the 1780s and 1790s.

Meanwhile, slavery became ever more enmeshed in the trade systems and economies of the United States and the larger Atlantic world. Instead of dying out as many of the founders of the new United States had anticipated, slavery had become more profitable than ever, flourishing in the South and expanding into new “slave states” like Kentucky and Tennessee. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, patented in 1794, encouraged enslavers to grow more cotton to supply the skyrocketing demand by northern and English textile manufacturers. Antislavery orators and writers, including many free Blacks, publicized the injustice and horrid conditions of slavery in the years leading up to the Civil War (1861-1865).

Despite the passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in 1865, African Americans struggled to exercise their newly acquired civil rights and obligations in the decades following the Civil War. Economic depression and the failure of southern Reconstruction to ensure those rights fueled a tremendous migration of southern Blacks to northern cities at the end of the 19th century. Sadly, racism and a glutted labor market prevented many African Americans from attaining the better life they sought in the North. Despite these setbacks, they established new cultural institutions and modified older ones to meet the demands of urban life.

Religion was an especially powerful and unifying force. Like the churches of newly arrived European immigrants, African American churches offered their members far more than a place to worship. Churches promoted cultural solidarity and provided spiritual and community support.

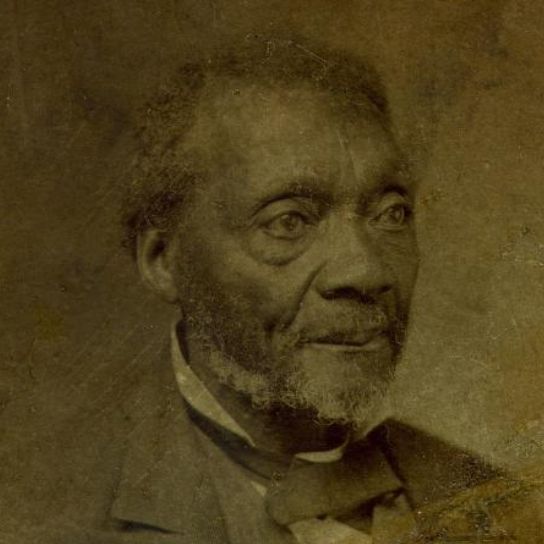

Schools established to educate African Americans such as the Hampton Institute in Virginia and the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama trained students for work in agricultural, domestic and industrial trades. Black leaders like Booker T. Washington believed economic self-sufficiency would lead to political equality with Whites. W.E.B. DuBois did not share Washington’s optimism that better education and job training would eliminate racism and other stumbling blocks to prosperity. DuBois and others stressed the need to elevate the minds and self-esteem of fellow African Americans. He insisted that, “The idea should not be simply to make men carpenters, but to make carpenters men.”