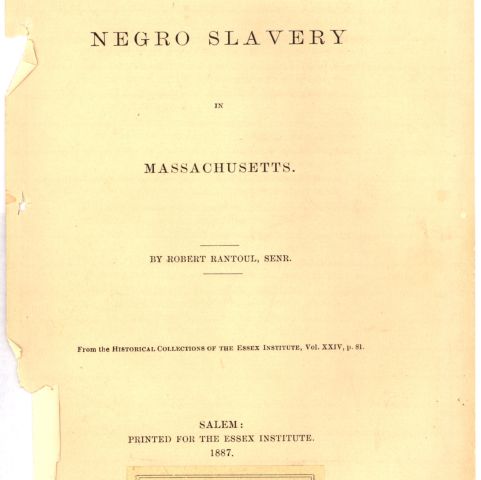

Slavery existed throughout the colonies before the American Revolution and few colonists challenged the prevailing belief system regarding indentured servitude and slavery. Economic, social, and geographic conditions fostered a distinctly New England pattern of slavery.

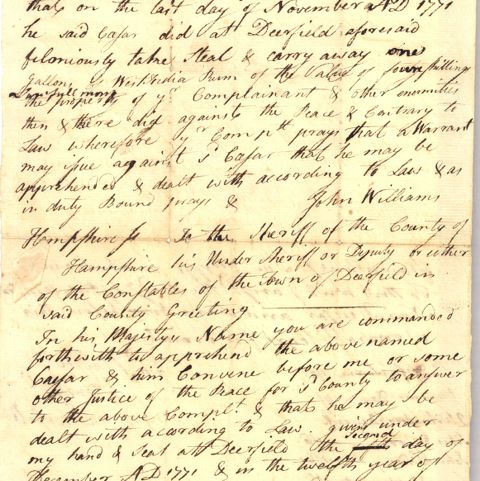

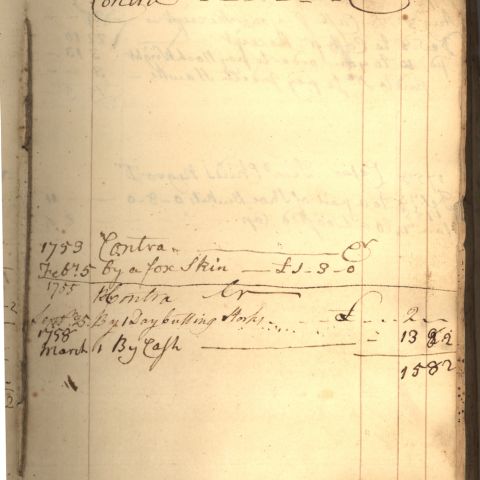

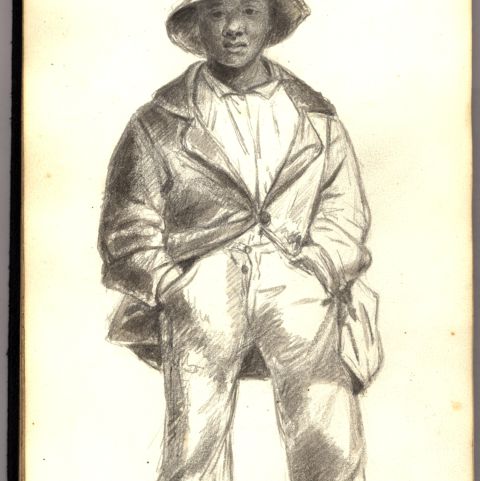

While few enslavers in New England held large numbers of people in bondage, the practice of owning another human being was not limited to the very wealthy. Many ministers, other professional men, and prosperous farmers had one or more enslaved man, woman or child. In New England, the enslaved were considered part of the household for which they labored. They often slept in the same building with the family, shared work spaces, and labored alongside family members. These living conditions in no way meant that enslaved people were perceived as equals. While Daniel Arms of Deerfield, for example, spent a January day in 1762 working alongside his enslaved man Titus, members of the church in town made Titus’ subordinate status clear when they publically chastised him in 1767 for “di[s]obedience to his master.”

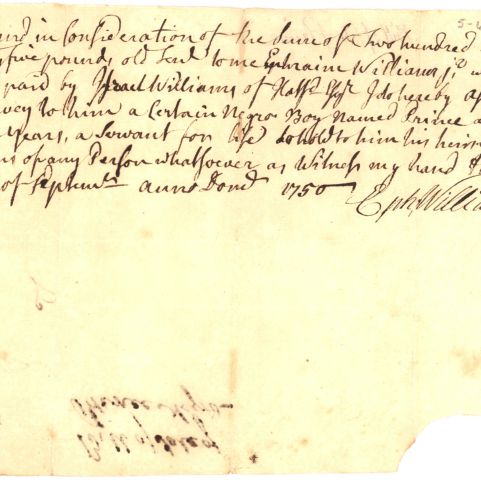

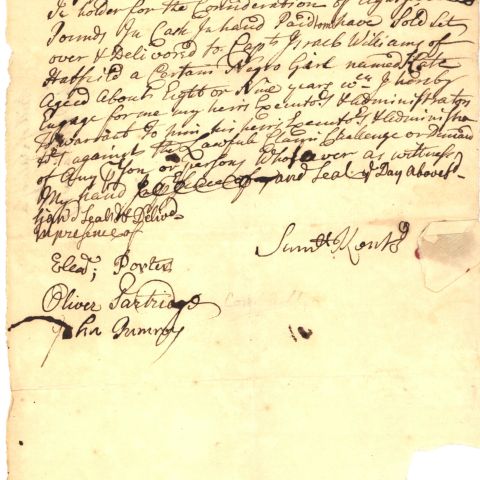

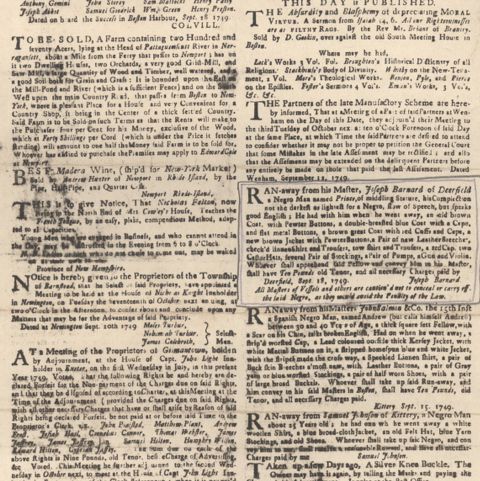

These work and living patterns encouraged White New Englanders purchasing human property to prefer children to teenagers or adults. John Watts of New York noted that for the northern markets, enslaved people sold best when they were “young, the younger the better if not quite children. Males are best.” Prospective enslavers reasoned that children were more likely to adjust quickly to life in a new household and would be more likely to form loyalties and attachments to the family they served. Enslavers also believed that African children would learn English more quickly than could adults. On September 25, 1750, a boy called Prince was enslaved by Israel Williams of Hatfield, Massachusetts. This bill of sale records the transaction that made this nine-year-old child Williams’s “servant for life.”