European explorers and settlers of the 17th century marveled at the abundance of life in North America. They referred repeatedly to its staggering bounty of fish, animal and plant life. John Josselyn wrote in 1675, of watching flocks of migrating passenger pigeons so huge that they “to my thinking had neither beginning nor ending, length nor breadth, and so thick that I could see no Sun.” Writers marveled over great forests of huge trees, the park-like aspect of the land, and the quality of the soil. The most breathtaking feature of all, however, was the sheer size of the continent. The land seemed limitless. More importantly, based on European ideas of what signified permanent habitation, the land was vacuum Domicilium, or “vacant land.” Of course, the apparent emptiness of this “New World” was more perceived than real. Native Americans had for thousands of years been careful stewards of the landscape the newcomers saw as vacant, or unused. Periodic burning by Native peoples, for example, had produced the park-like meadows that were part of a complex ecosystem. Those meadows in turn supported the abundance of animal and plant life the settlers found so remarkable. European ideas of land ownership proved incompatible with Native American beliefs about land use and homelands. Confusion, disagreements and conflict yielded tragic results. The European relationship with the land quickly became an integral part of the new America’s identity. As early as the 1770s, J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur wrote in his Letters from an American Farmer, “What should we American farmers be without the distinct possession of the soil? It feeds, it clothes us; from it we draw…our best meat, our richest drink…No wonder we should thus cherish its possession; no wonder that so many Europeans who have never been able to say that such portion of land was theirs cross the Atlantic to realize that happiness. This formerly rude soil has been converted by my father into a pleasant farm, and in return, it has established all our rights; on it is founded our rank, our freedom, our power as citizens, our importance as inhabitants of such a district.” …this is what may be called the true and the only philosophy of the American farmer.” The industrial and technological advances of the 19th and 20th centuries abruptly severed millions of Americans from the land. Cities teemed with factory workers and businessmen who had left farms or who had never lived on one. Meanwhile, industry and a revolution in transportation changed the lives of farmers and their families. Change came in the form of new machines, new techniques and expanded markets. The railroad brought competition to farmers in the East and opportunity for those in the Midwest. Meanwhile, city-dwellers proved reluctant to give up completely their connection to the land. Summer resort communities and summer camps flourished as Americans turned to the land to restore their spiritual and physical health.

Turns of the Centuries: The Land

Explore this theme

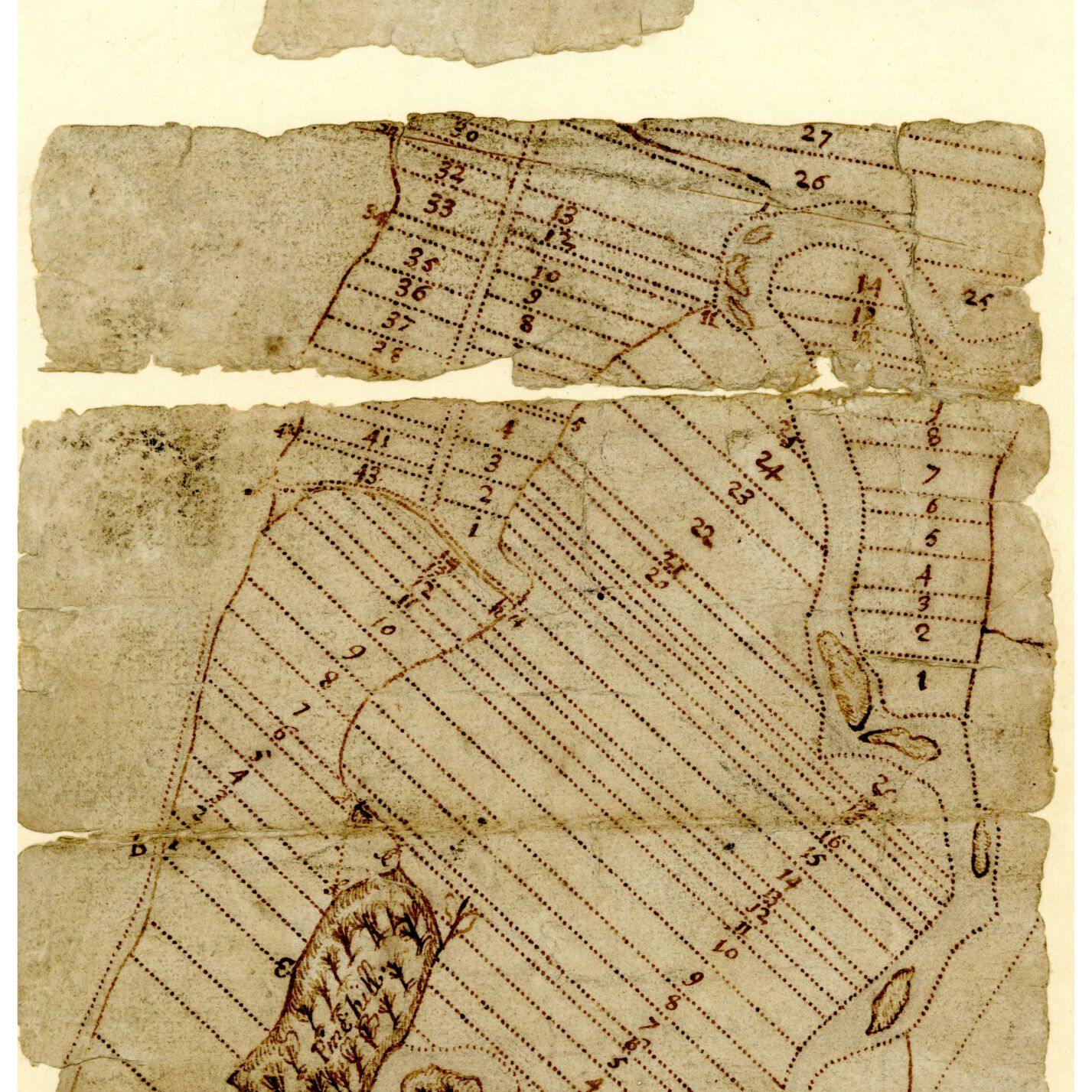

The Land: 1680–1720

The Connecticut River Valley contains some of the richest agricultural lands in the northeast. It has been a vital crossroads for Native peoples for more than 10,000 years.

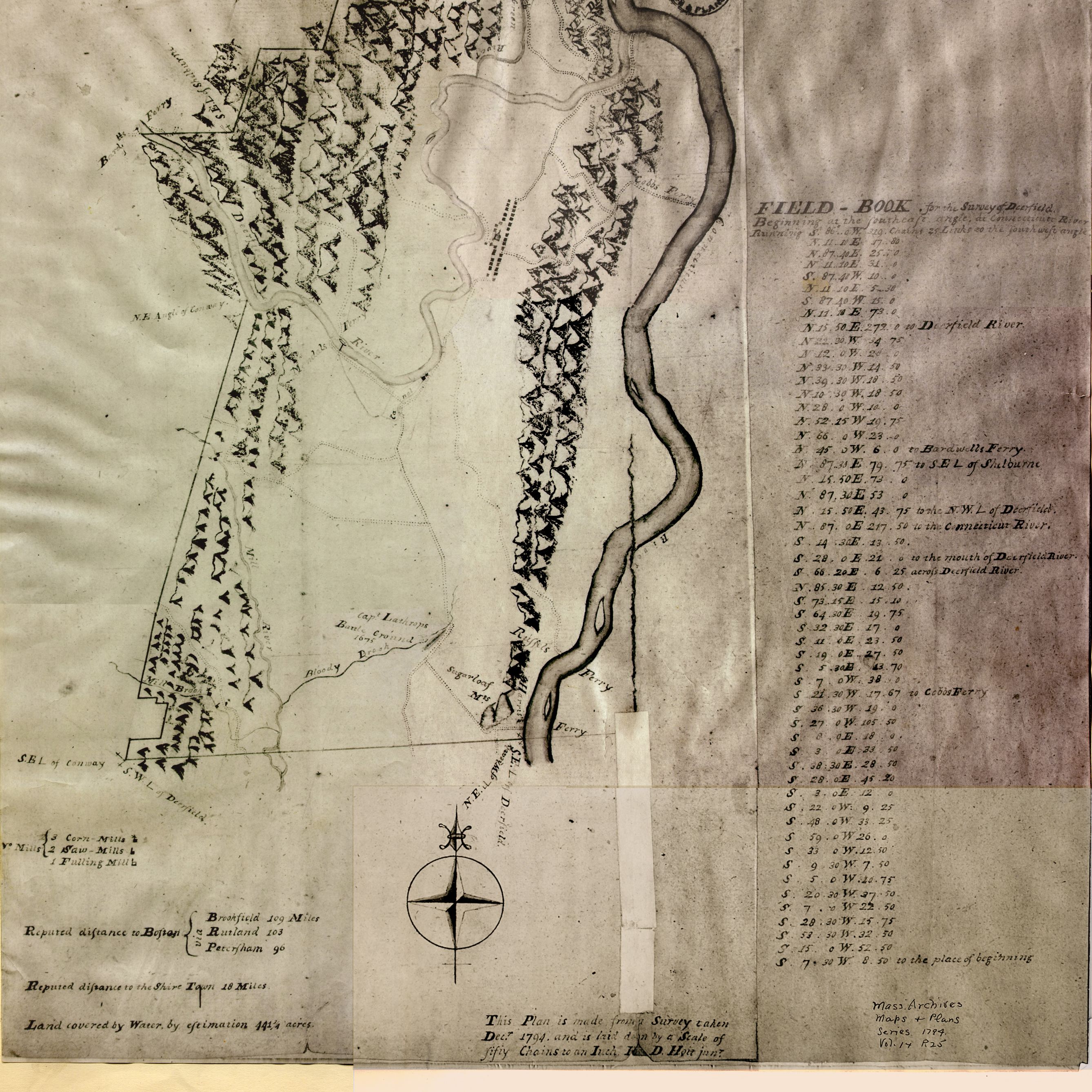

The Land: 1780–1820

By the early 1800s, a century and a half of European settlement and land use had transformed the landscape of the eastern seaboard. In New England, town commons took on a park-like appearance and their public role expanded.

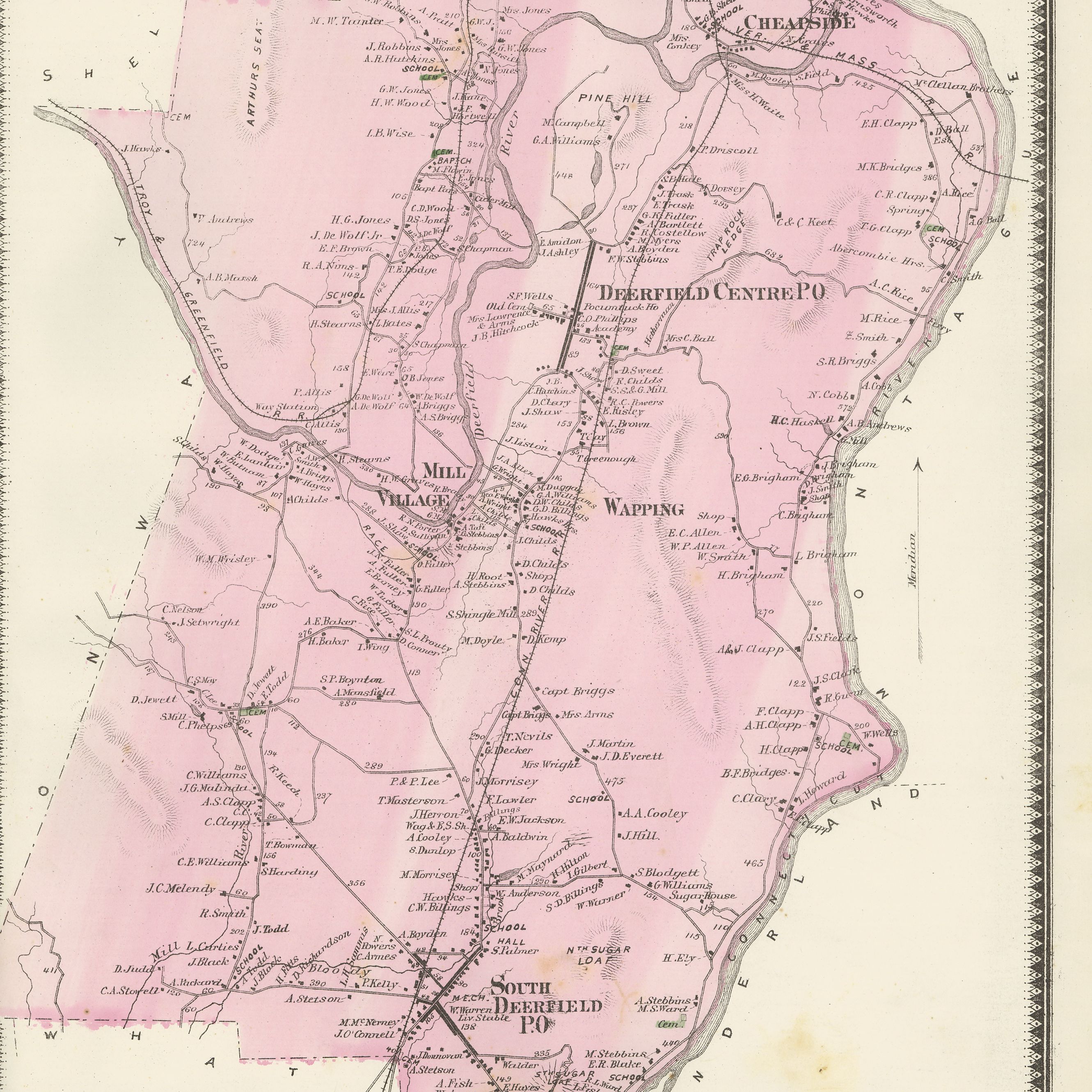

The Land: 1880–1920

For the first time, more Americans lived in cities than on farms in the countryside. Urban landscapes and industries competed with the old agrarian lifestyle and culture. Even in rural areas, factories and their employees transformed the landscape and the local economy.