The Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts contains some of the richest agricultural lands in the Northeast and has been a vital crossroads for Indigenous peoples for more than 10,000 years. Numerous trails and waterways connected settlements to each other, facilitating trade networks, kinship connections, and political alliances. The weather, the seasons, and the land itself have always determined how, when, and where people hunted, gathered, planted, harvested, fished, and celebrated. Sustained contact with Europeans beginning in the 15th century subjected these lifeways to severe stress. Euro-American explorations, wars, and settlement forced Indigenous peoples to respond, resist, and adapt to changing social and economic relations, rapidly shifting political alliances, population losses from disease and warfare, and loss of land and natural resources. Many Algonquian people continued to move through their homelands, traveling ancient routes that enabled them to maintain kinship relations and respond to occupational and resource opportunities. Others settled permanently in small enclaves or worked, lived, and intermarried with Euro-Americans and African Americans. During the 1700s, the Connecticut River Valley and the Berkshire Mountains in Massachusetts had been considered the “frontier.” From the late 1800s into the early 1900s, Euro-American people and goods moving westward, and wars of expansion took a terrible toll on Western Indigenous nations and economies. By the early 1800s, Algonquian peoples in New England and Canada, and Iroquoian peoples in New York and Pennsylvania were entering their third century of struggle and adaptation. Many Northeastern peoples had adopted Euro-American material goods, occupations, and lifestyles as they settled in towns, served in the military, farmed, and marketed their handicrafts to their White neighbors.

As New England entered the industrial era and White settlement expanded across the continent, Euro-American observers ignored the persistence and adaptability of Indigenous peoples. They were relegated to the past as tragic “remnants of a dying race,” or romantic “last of the Indians,” despite innumerable legal documents, family histories, account books, and other records that reveal their continued presence.

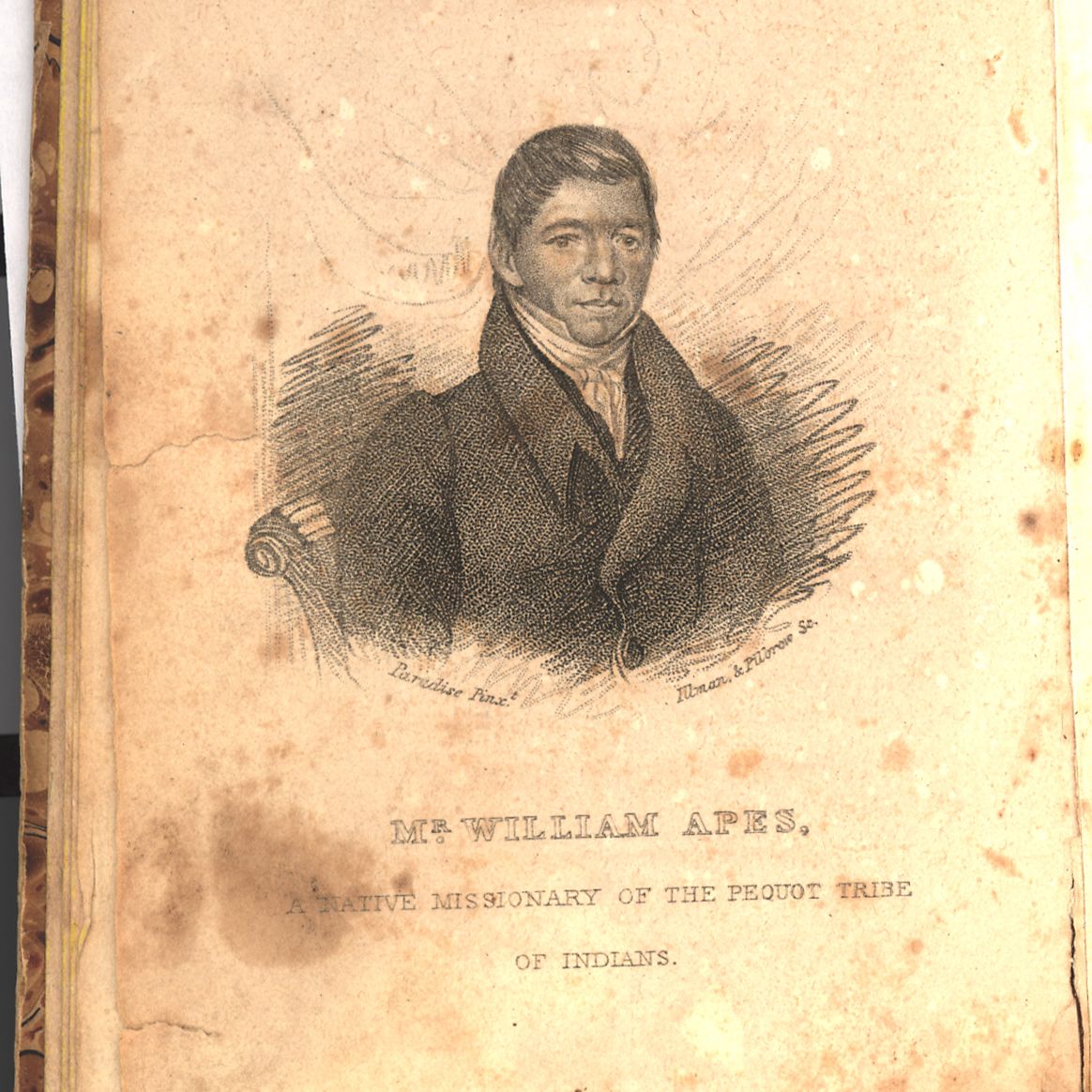

Not only were Indigenous peoples considered to be dying out, but those who remained visible faced removal and whitewashing. Euro-Americans exerted tremendous pressure on them to conform to White culture, sending missionaries to spread Christianity to the “heathens” and forcing Western tribes onto reservations. Children were kidnapped from their families and sent to boarding schools where, in the words of Richard Henry Pratt of the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania, the goal was to “Kill the Indian, save the Man.” Euro-American New England politicians created the “Native American” political party, whose agenda was to deport Indigenous peoples, Africans, and the Irish so that America would be preserved for the “Native Americans,” meaning White descendants of the Puritan founders.

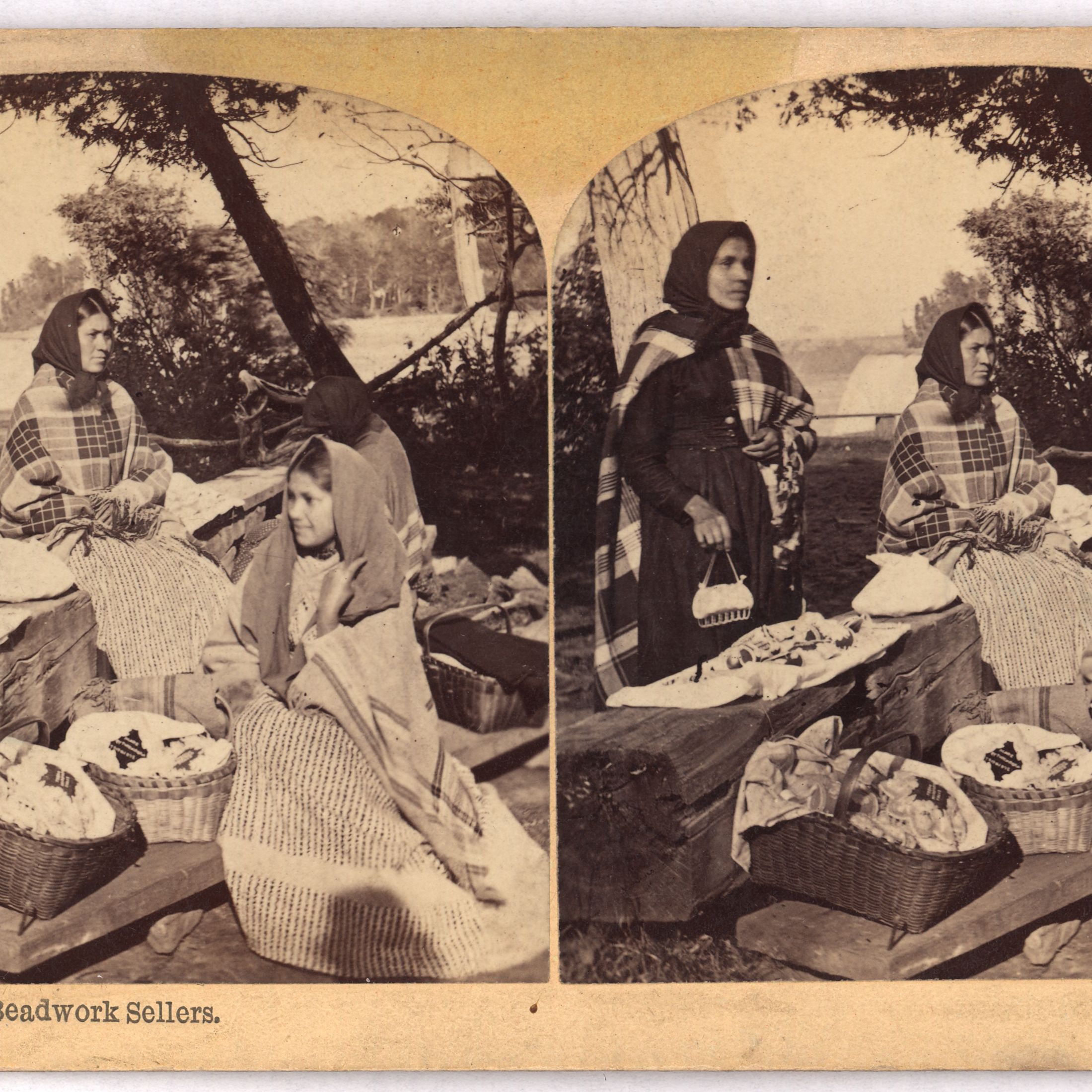

At the same time, however, Euro-Americans sought superficial, romantic ways to connect with Native American cultures. Tourism became a thriving industry as many Northeastern Indigenous peoples, sometimes wearing Western Plains clothing or their own traditional garb, successfully marketed their handicrafts such as basketry and beadwork to an eager White audience. Some worked as New York models and Hollywood performers and still others created fraternal pan-Indigenous organizations. The Algonquians who formed “The Indian Council of New England” in the 1920s, initiated the inter-tribal powwow that is still popular today.

Meanwhile, Native Americans in New England continued “hiding in plain sight” by practicing the strategies of integration and anonymity they had developed over the previous century, persisting in their original homelands despite discrimination, forced assimilation, and historical reports of their disappearance.