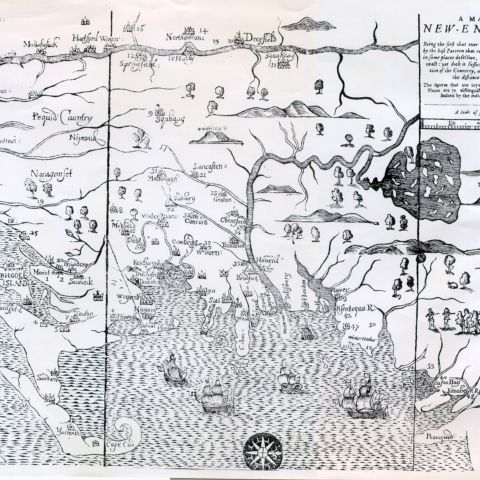

By the early 1800s, Indigenous peoples in Southern New England were entering their third century of persisting, despite the odds, against colonial invasion, disease, and conflict. Many White New Englanders nonetheless regarded Native people as relics of the past. Town historians and novelists like James Fenimore Cooper, author of The Last of the Mohicans, began to refer nostalgically to the “disappearance” of the region’s Native inhabitants.

These assumptions and attitudes obscured the continuous and ongoing presence of Native American people in the region. Although the dominant culture often rendered them invisible, their presence is recorded in legal documents, family histories, account books, and other sources. Many Native families continued traveling through their familiar homelands, following occupational opportunities and seasonal rhythms, while maintaining kinship ties and reaffirming connections to the land. Some settled permanently in rural communities or urban enclaves. Others worked, lived, or married across racial lines, mixing in with White and African American communities.

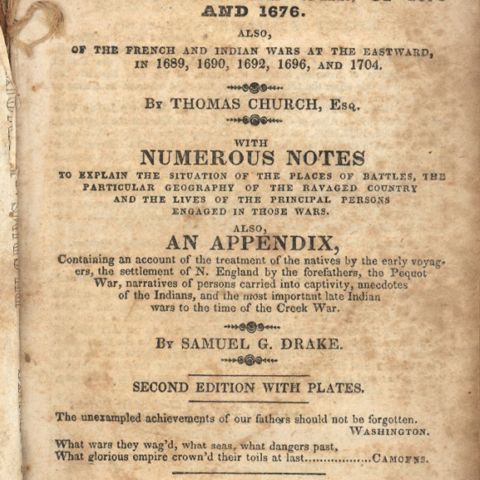

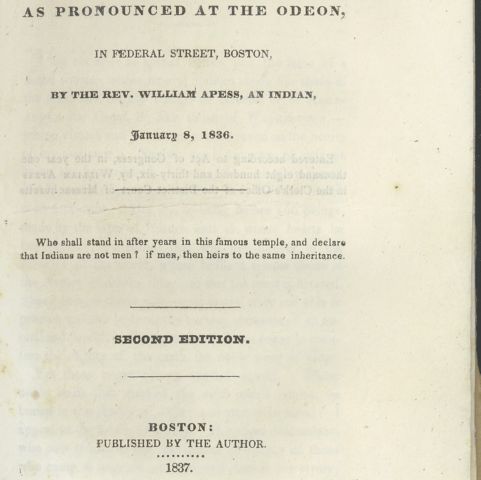

William Apes (1798-1839; also spelled Apess) was a Pequot writer, orator, and preacher of mixed ancestry (Native, Black, and White) born in Colrain, Massachusetts. His written works and activities provide insightful glimpses of Native experiences and perspectives in southern New England during the early 1800s. Apes stood out as an advocate for Indigenous rights during a period of racial discrimination, poverty, and disenfranchisement. In 1836, he delivered a speech titled “Eulogy on King Philip”, that defied traditional White interpretations of Metacom’s Rebellion/King Philip’s War in 1675-1676, and the Wampanoag leader for whom it was named.

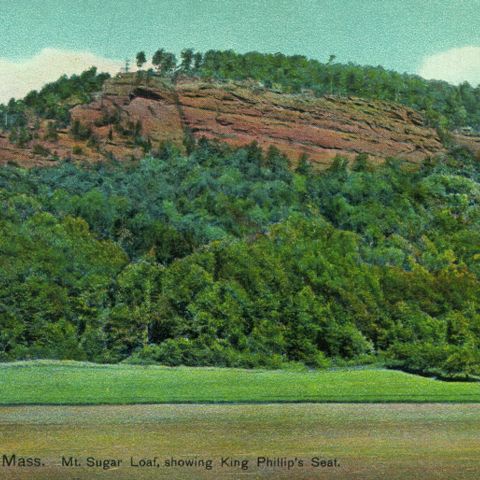

English settlers and their descendants viewed Metacom as a savage rebel who led the bloodiest war, per capita, ever fought on American soil. They celebrated his death, and English illustrations of his last moments show him lying ignominiously face down in the mud. William Apes, in contrast, portrayed Metacom as a patriot, “a martyr to his cause” who died for his country. In a deliberate contrast to English descriptions, Apes depicted Metacom’s death as a noble and tragic scene.

For Apes, the tragic events of King Philip’s War echoed through the continuing racism and injustices that Indigenous people were experiencing during the early 1800s, more than a century after the war’s end. During the same era when Apes was penning his scathing indictment of English colonial policy, the United States government was endorsing the removal of Indigenous peoples from Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Federal policy forced thousands of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole people from their homes, relocating them to reservations in Oklahoma. Like his other writings and orations, Apes’ eulogy and its frontispiece publicized the plight of Indigenous people in the past and the injustices they continued to suffer in the present.