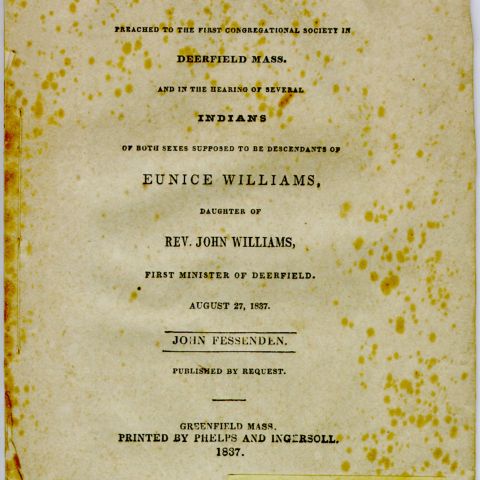

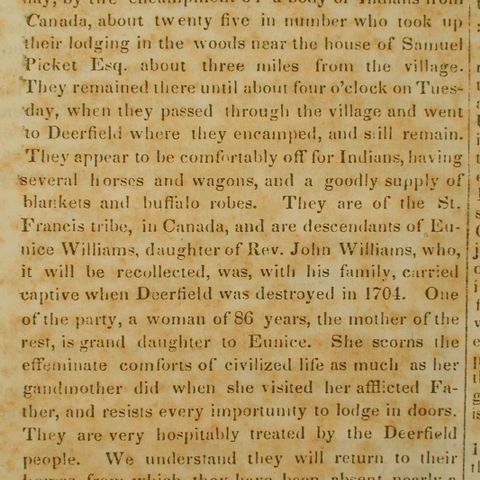

In August of 1837, the Greenfield Gazette and Mercury newspaper reported that a group of Abenaki Indians were camped in Deerfield, Massachusetts. Their appearance, according to the Gazette, caused “considerable emotion” among Deerfield residents who were told that some of these visitors were descended from Eunice Williams. She was one of the many English inhabitants taken captive in a 1704 raid by Canadian French soldiers and their Indigenous allies. Her subsequent refusal to return to Deerfield, conversion to Catholicism, and marriage to a Native man grieved her English father and gained her everlasting notoriety in Deerfield as an unredeemed captive.

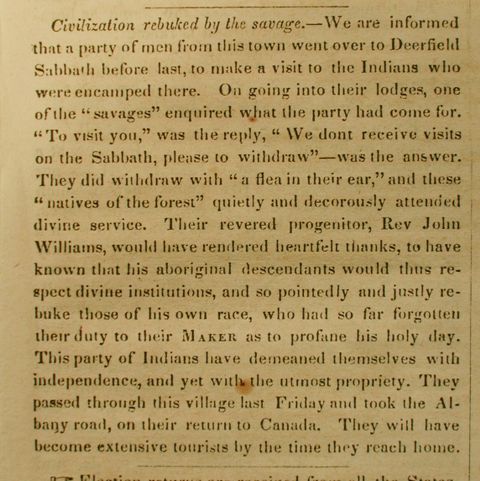

According to the Reverend John Fessenden, members of the Williams family “were not slow to admit” the ties of kinship with these Abenaki visitors and “uniformly called them, ‘our cousins.’” Of particular interest was the wish of the eldest Native woman, a great-granddaughter of Eunice Williams, to visit the burial place of Eunice’s mother. The Gazette and Mercury reported that the “Williams Indians,” who lived in the St. Francis mission village now called Odanak, in Québec, departed for Canada by way of the Albany road, observing that they “will have become extensive tourists by the time they reach home.” This last remark highlights a general lack of understanding among White observers regarding the broader purposes and context of Native travel patterns. Except for the visit to the gravesite, neither this trip nor the route they took were unusual events. Abenaki and other Indigenous peoples in the Northeast routinely traded, visited, and exchanged gifts as they moved through their traditional homelands along ancient travel routes. In this case, the Abenaki group had traveled south through New York, into Vermont, and down the Connecticut River to Deerfield. From there, they would go west to Albany, New York, traveling along the Hudson River to join other Indigenous people selling baskets in the thriving resort town of Saratoga Springs. Then they would make their way northward through Lake George, to Lake Champlain, and back to St. Francis.

The 1837 trip was unusual because it was documented in written reports, given the degree of attention it received from White observers intrigued by the visitors’ connection to the Williams family. Sophie Watso, an Abenaki descendent of Kanenstenhawi (Eunice Williams) gave this covered splint basket to Caroline Williams of Deerfield during that visit. The inscription on the bottom of the basket reads: “Basket Given me September 1837 / By Sophie one of the St. Francis Indians / Connected with the Williams family.”