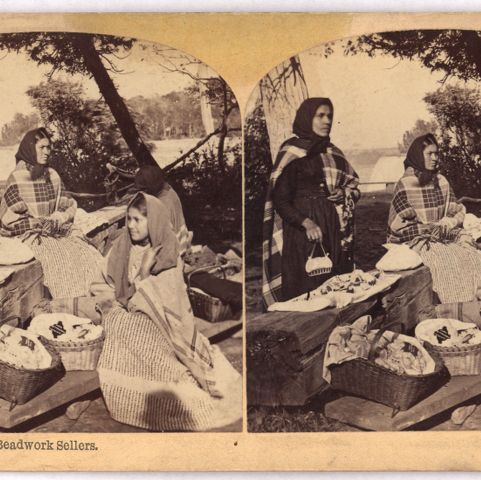

Although Indigenous peoples had been expected to assimilate and conform to American culture, those who retained traditional practices were objects of fascination to their White neighbors. The emergence of the tourism industry, during the late 1800s and early 1900s, promoted a variety of ways to interact with Native American cultures. Tourism became a thriving industry as many Indigenous people successfully marketed their ethnicity to an eager White audience. For example, Satekenhatie Marion Patton Philips of Kahnawake, Québec, recalled that as a young woman, she helped her mother produce beadwork to sell at the Toronto Exposition, beading items such as cloth horseshoes, boots, hearts, and picture frames. Native families traveled to popular tourist centers, setting up picturesque encampments to make and sell baskets and beadwork at hotels in the White Mountains, and in resort towns like Lake George, Saratoga Springs, and Niagara Falls.

Since Native families in these camps focused primarily on meeting the desires and tastes of customers, their limited interactions did little to communicate the richness and autonomy of Indigenous cultures. White Americans could “experience” Indigenous cultures by attending public ceremonies and dances, and children across the nation participated in organizations such as the Boy Scouts and the Campfire Girls that, while they emphasized Native American crafts, offered what was often pseudo-Native American culture. Some summer camps in New England, however, such as the one organized by Smith College student Angel DeCora (Ho-Chunk) and author Charles Eastman (Lakota) strove to teach authentic Native crafts and activities. Scenic travel routes, like the Mohawk Trail in Western Massachusetts, also fed tourist appetites for Indigenous exoticism and “untamed” landscapes, while allowing them to indulge their growing love affair with the automobile.

Stylized images of Native Americans were part of the marketing for tourist attractions. Artists like Frederick Remington, and moviemakers like John Ford, created images that generally romanticized and depersonalized “real” Native American people by promoting dramatic stereotypes. Such images were, for many Whites, their only exposure to Indigenous cultures. Native American images, art, and culture symbolized a connection with nature that many White Americans had lost. Yet, some Native people successfully used these venues for their own purposes. Elijah Tahamont, an Abenaki from Lake George, New York, was a popular and highly paid orator and model who posed for Remington, acted in Ford’s early silent movies, and even scripted films of his own.