In 1631, John Winthrop of Boston spent a terrifying night pacing in front of his fire, singing psalms to keep up his spirits in the dark and frightening forest in which he had lost his way–a half mile from his house. For him and his fellow colonists, they had immigrated to a “howling wilderness.” The land was not under European-style cultivation and there were no permanent, year-round dwellings. In their minds, the land was empty, there for the taking. Roger Williams, a Puritan minster who eventually helped to found Rhode Island, was unusual in his insistence that the King of England had no right to grant land that belonged to Indigenous inhabitants. The Reverend John Cotton, an immigrant to Massachusetts Bay, expressed the more common belief when he wrote, “In a vacant soyl, he that taketh possession of it, and bestoweth culture and husbandry upon it, his Right it is.”

In actuality, the original inhabitants had modified this supposedly vacant landscape through thousands of years of hunting, gathering, planting, and settlement. The way in which Native Americans moved across the land for different purposes and at different seasons was, however, an unfamiliar concept to the sedentary English. Too, epidemics of Old World diseases had ravaged thousands of Indigenous peoples and depopulated many areas before the first European settlers arrived. This encouraged newcomers like Robert Cushman of Plymouth to consider the land they saw as “spacious and void.”

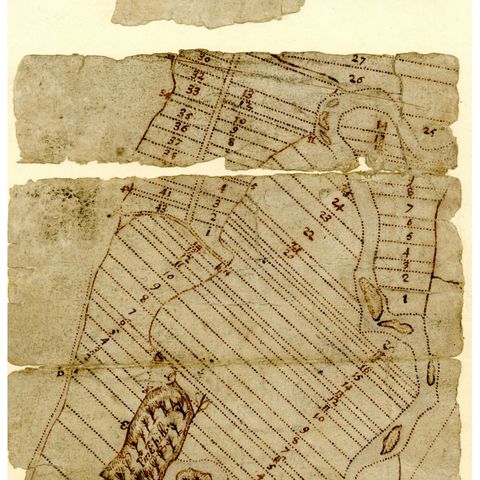

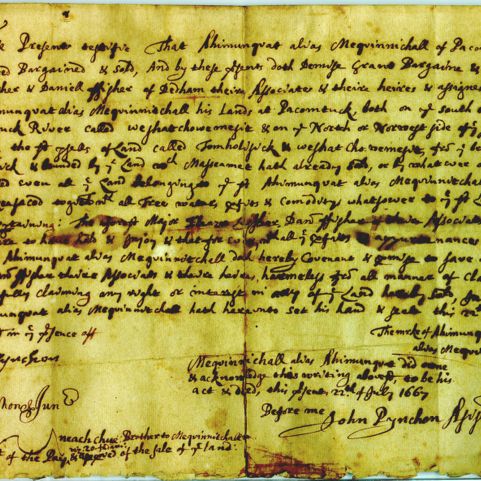

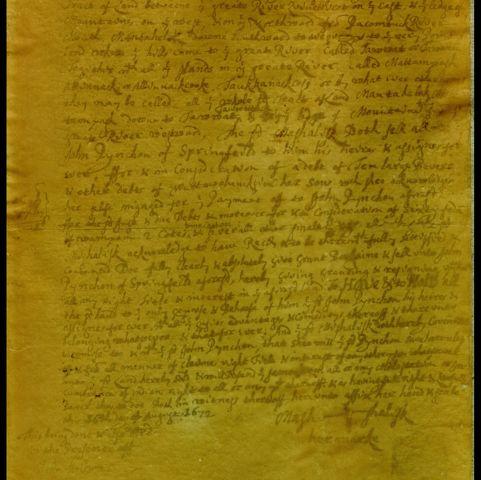

Pictured is a deed for land purchased from the Pocumtuck people in 1666. It became the present-day town of Deerfield, Massachusetts. Chauk, the man chosen by the English to negotiate with, was not Pocumtuck, and did not reside on their homeland. In addition, Indigenous peoples in New England didn’t believe in exclusive ownership. They saw themselves as land stewards. Most likely Chauk erroneously understood that he was putting his mark on an agreement to share the land. Disagreements immediately arose as settlers moved into Deerfield and elsewhere and asserted what they saw as their exclusive rights to the land they had purchased. These conflicts over the land yielded tragic results, forcing many Indigenous peoples in Western Massachusetts to leave their homelands.