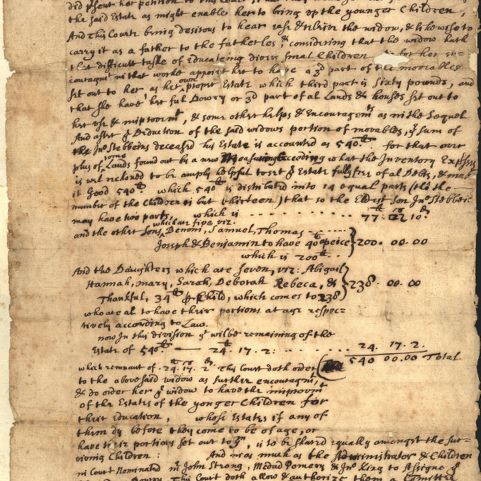

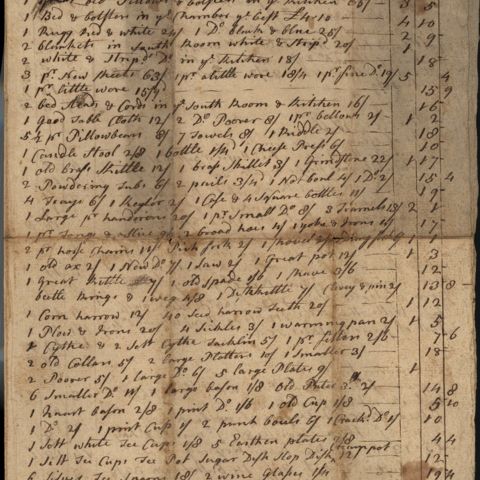

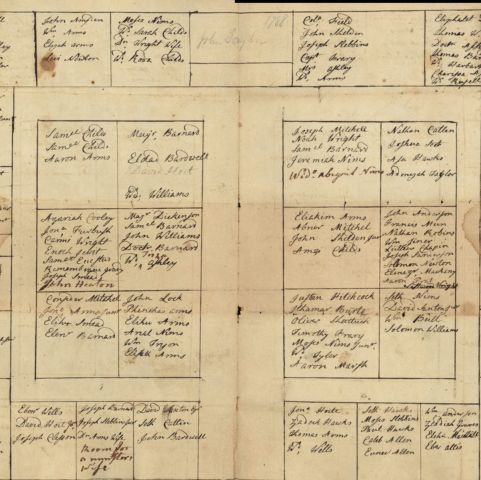

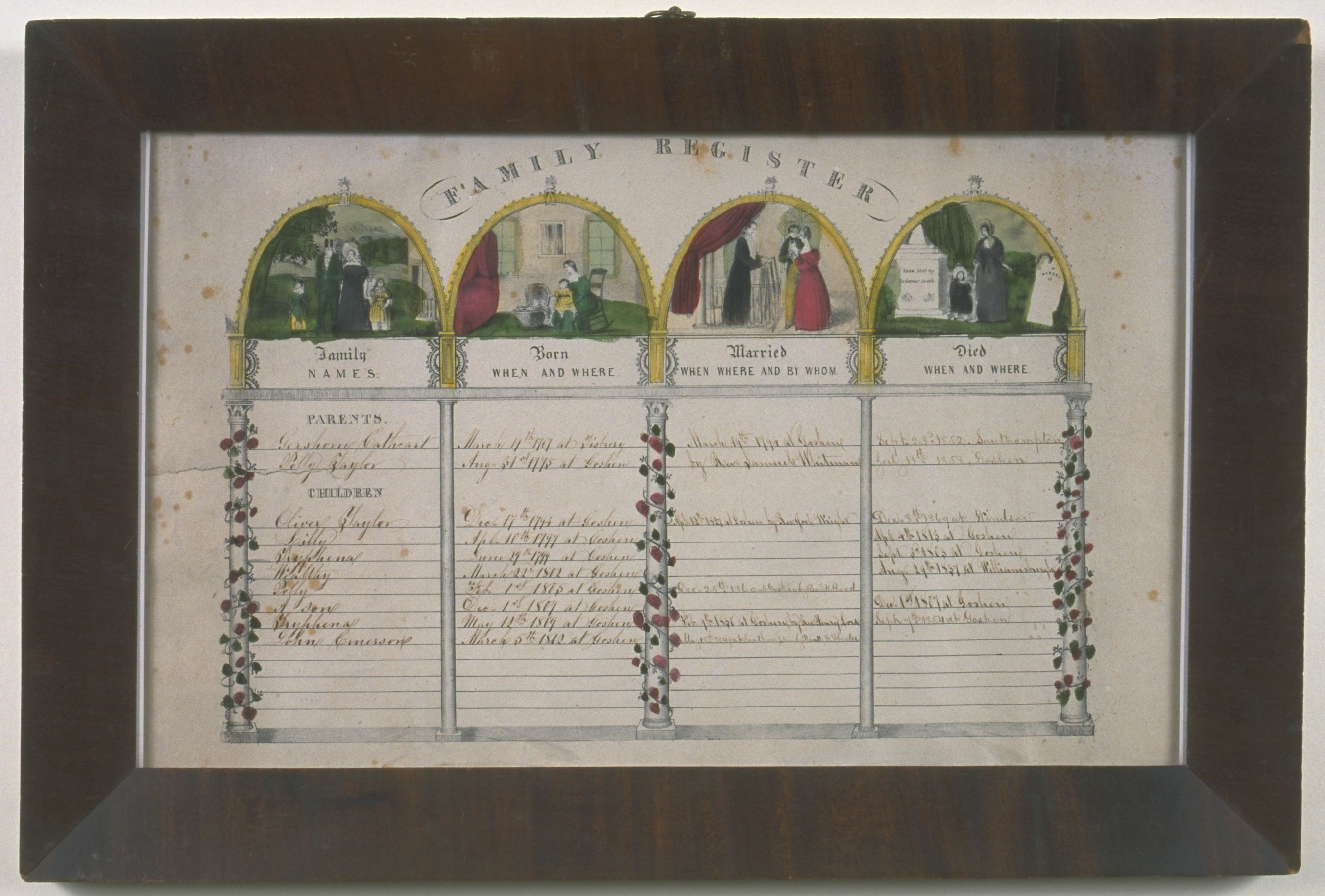

Colonial society, like that of Europe, was hierarchical. A person’s wealth, status and gender determined their place in that society. Ministers were respected as spiritual and intellectual leaders. Fathers were the de facto heads of individual households. Gender automatically relegated women to a subordinate status. Their responsibilities included ensuring the smooth operation of the household and caring for the children. Religion and the changing seasons governed family life in colonial America. The Puritans of New England in particular were an intensely religious people. Their belief that direct access to the word of God was one of mankind’s most precious privileges spawned a high literacy rate among that set them apart from other English colonists. The agrarian cycles of planting and harvest defined the year throughout the colonies. Real estate (land) and a dwelling house were the symbols of prosperity in a world where farming was the dominant occupation. Economic, cultural and political factors also affected settlement patterns. In New England, the town represented community, interdependence and permanence. This utopian vision of a planned community stood in stark contrast to the widely dispersed plantations and farms that characterized settlement in Virginia and other southern colonies. Farming was the dominant occupation because New England towns were meant to be permanent and no settlement could survive if it could not feed itself. Settlements were in the form of towns, not individual homesteads, and the members of the communities were mutually dependent. Nature and the patterns of work shaped the workdays; plantings and harvests defined the years. Marriage was the normal condition for adults and large families of 5 to 10 living children were not unusual. Resulting population pressures and decreasing crop yields quickly began to strain resources in New England towns. Similar pressures encouraged the centrifugal settlement of the Middle and Southern colonies. Westward movement and expansion accelerated at the end of the eighteenth century as Americans sought to attain the economic and political promises of the American Revolution. By the early nineteenth century, factory work offered to American men and women an alternative to agriculture. The Industrial Revolution irrevocably altered family relationships and lifestyles. Women leaving family farms gained economic and political autonomy as they entered an industrial work force. Industrialization and new technology allowed many families virtually to ignore the seasonal cycle that once regulated the rhythms of life. As farming declined and population increased, both the farm products and many of the farmers themselves gravitated to the cities. Textile mills provided work for women as well as men, and this began to make changes in the family structure. As the marketplace gained in influence, the role of the church became less important and industrialization, with electricity and central heating, allowed families to virtually ignore the seasonal cycle of life previously so critical to life in the 17th century.

Turn of the Century Theme: Family Life

Details

| Topic | Agriculture, Farming Commerce, Business, Trade, Consumerism Family, Children, Marriage, Courtship Gender, Gender Roles, Women Industry, Occupation, Work Religion, Church, Meetings & Revivals |

| Era | Colonial settlement, 1620–1762 Revolutionary America, 1763–1783 The New Nation, 1784–1815 National Expansion and Reform, 1816–1860 Rise of Industrial America, 1878–1899 |