A growing network of turnpikes, canals and better roads reduced shipping costs and provided Americans access to more goods in the decades following the American Revolution. The lack of specie, or gold and silver, still defined the economy of early America, however. The discovery of large amounts of silver and gold in the West was still decades in the future. An elaborate system of credit evolved due to the constant shortage of “hard” money. People exchanged goods and services and balanced accounts with small amounts of cash, paper money or personal “notes”. A good credit reputation was essential; to be a person of “no account” meant exile from this credit-driven economy.

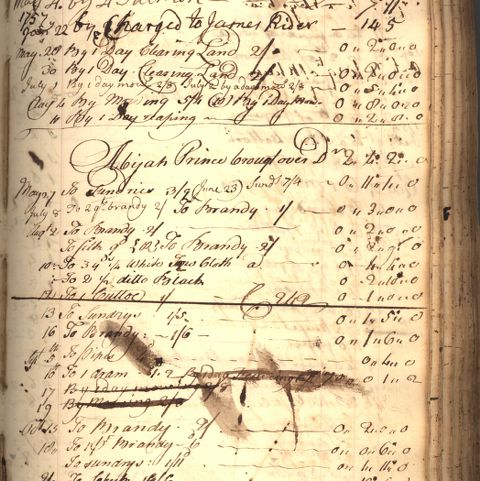

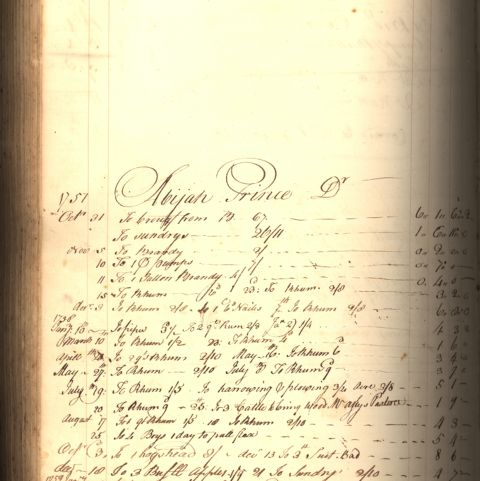

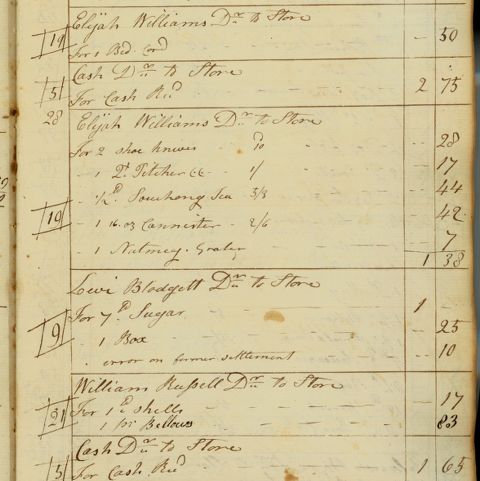

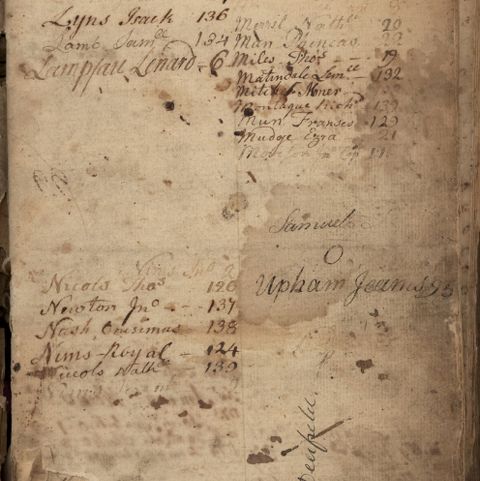

Many people purchased blank ledger books to record their accounts. The entries they made in these account books helped them to keep track of what they purchased, how much money it cost and to whom it was due. Account books also recorded who purchased goods and services or borrowed money from the owner of the account book.

Keeping accurate accounts required legible penmanship, vigilance and good math skills. Surviving account books provide valuable information about the economic activity of the person who owned it. Most names in account book entries are male. Although women played a critical role in producing and consuming goods of all sorts, their economic activity usually appeared under accounts headed by a husband, father, or other male relative. Because they frequently listed dozens or even hundreds of economic partners, account books also are a window onto the economic and social life of a community as a whole.

This page from Zebulon White’s account book details his account with James Winslow. Both men were from Deerfield, Massachusetts. Note the cash values assigned to each item listed. The men signed their names to signify their agreement when they settled the account in 1792.